NEP: Children’s Literature and Reading Promotion – Missing Link?

Beyond a fleeting mention of reading for enjoyment, the focus on promoting Indian languages is more on creating vocabulary that keeps pace with new developments as well as on teaching of Indian (including classical) languages.

The draft National Policy on Education (NEP), 2019 talks at length about three language formula, education in the local language/mother tongue, and exposure to and promotion of Indian languages. It has rightly emphasised local language or home language learning, especially in early years to ensure children are able to understand what they read. But when it comes to promotion of Indian languages the policy does not talk about the role of literature in enabling language learning in a comprehensive manner. The role of good quality story books, contextual and multilingual children’s literature and vibrant libraries in promoting language learning is not adequately dealt with.

Beyond a fleeting mention of reading for enjoyment, the focus on promoting Indian languages is more on creating vocabulary that keeps pace with new developments as well as on teaching of Indian (including classical) languages. Since languages flourish through actual use, enjoyment cannot be a peripheral goal of language and literacy education. The policy gives reference to European countries that have systems to preserve their languages etc. What it misses out is that European countries have a vibrant children’s publishing, government support, large penetration of public and school libraries.

Support Publishing for Children:

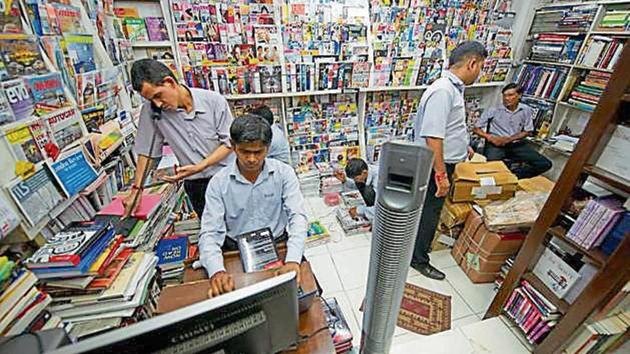

A language promotion policy should focus strongly on supporting children’s publishing and stocking government school libraries with original and contextual literature. Notably, less than half of the content printed in regional languages is original. Books for children are text heavy with small font sizes and no illustrations. For very young children, (0-4) board books are the international standard. The United Kingdom has a Bookstart programme that provides board books to children before they are 12 months old and again aged 3-4 years. If we want children to enjoy different languages we should aim to encourage a love of books, stories and rhymes from as early as possible. But development of good quality contextual picture books is time and cost intensive and regional language publishers have not engaged in this. Large scale procurement of picture books for school libraries by states will contribute to promoting access to quality literature. In this also government norms should not limit procurement of books only to the National Book Trust and NCERT books but welcome books based on quality by other publishers.

Encourage writing in Indian languages:

In language publishing, while writing for adults is established, writing and illustrating for children has not received adequate attention. There is an urgent need to support writers in regional languages. Authentic voices who can represent the diversity of children’s experiences (such as working children), their tastes and lived reality is missing. Children want to read books where they find themselves and use stories as a means to understand themselves and the world around them. They also want to read books about children different from them. While the policy talks of research funding for Indian languages, it must recommend setting up a writer’s and illustrator’s fellowship/fund in Indian languages, so that young people are encouraged to write literary pieces for children. The fund should support writers, illustrators and publishers’ workshops that groom a new generation of writers and publishers so that we are able to build a generation of readers and thinkers.

Libraries for All:

The policy focuses on strong Indian language and literature programmes across higher educational institutions. There is a danger in limiting language and literature promotion to universities. In the past this has meant inaccessibility of books, reading and engagement with literature for disadvantaged children, youth and communities. Instead the policy should explicitly include public, school and community libraries as critical points for promotion and make weekly library periods compulsory. The policy does mention expansion of public and school libraries but does not give a comprehensive roadmap for same. School libraries should be accessible with strong collection of books/ audio books/ePubs in languages. Community libraries as has been done in Kerala, will go a long way in promoting languages by giving people access to books and literature.

Teachers as Readers:

To promote Indian languages and literature it is essential that teachers start reading. Unless teachers understand why reading and literature is important they will not be able to translate that into practice. Integrating library into different subjects and encouraging children to read beyond the textbook is essential if children are expected to be fluent in multiple languages, as well as think critically. A teacher in charge of library often does not have the skills to read aloud, tell a story, or conduct book extension activities that may attract children towards reading. A strong reading promotion component needs to become part of pre-service and in service teacher education.

Unless we deep dive into the challenges and make solutions part of the long term vision of education, we will risk losing the rich diversity of languages we are trying to preserve.

(The author leads the leads the Parag Initiative at Tata Trusts that promotes reading for pleasure by supporting development of children’s literature in Indian languages and access to school libraries)