Lavish Bribes and Wooden Potties: A Short History of Conclaves

The drama and intrigue of a modern papal election can be movie-worthy, but the level of skulduggery these days is modest compared with past centuries.

To break the deadlock, the local population locked the cardinals up in the hall of a papal palace, reduced their diet to bread and water and bricked up the windows. They even removed the roof—ostensibly to allow the Holy Spirit direct access, in practice to expose them to the elements.

That conclave in the town of Viterbo, near Rome, began in 1268 and was the longest in history. The lengthy lock-in gave papal elections their modern name: cum clave, Latin for “with key.” The eventual winner, Pope Gregory X, sought to avoid a repeat by imposing some ground rules that still govern conclaves today, including strict seclusion, daily voting and a degree of discomfort.

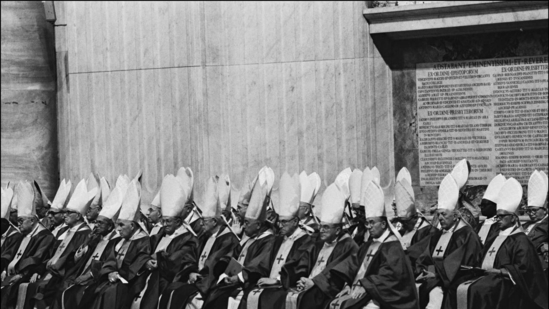

The conclave beginning on Wednesday to elect a successor to the late Pope Francis is likely to be much shorter. The drama and intrigue of a modern papal election can be movie-worthy, but the level of skulduggery these days is modest compared with past centuries, when political manipulation and outright bribery were common.

What happened during the period of seclusion was rarely a mystery to Europe’s worldly rulers, who thought the choice of pope too important to be left to the church alone. When cardinals met in 1549, an envoy for the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V let them know that Europe’s most powerful man would even “know when they urinate,” as American historian Frederic J. Baumgartner recounts his book “Behind Locked Doors: A History of the Papal Elections.”

Many of the rituals at conclaves are relatively modern. The Sistine Chapel became the sole location for papal elections only in 1878. The custom of using black smoke to indicate an unsuccessful ballot and white smoke to show there is a new pope didn’t exist before then.

“The conclave is a strange myth magnet. It is often presented as a practically timeless institution where mysterious events occur and peculiar rituals are followed as cardinals discern the Holy Spirit’s voting preference,” said Alberto Melloni, a historian and author of a new book called “The Conclave and the Election of the Pope.”

“None of that is true. The conclave is a practical response to a practical requirement,” namely to ensure a quick and peaceful transition between popes, Melloni said.

In early Christianity, the selection of the bishop of Rome was a fluid process often involving the local clergy, powerful notables and popular acclaim. Cardinals didn’t even exist until the 11th century and initially there were only 12 of them, like the number of Apostles. The number of cardinals has progressively grown, and a record 133 cardinals are expected to vote in this week’s conclave.

Two-thirds of them need to vote for a candidate to make him pope, a requirement that has been in place since the 12th century.

Modern conclaves have generally lasted between two to five days. The shortest-ever conclave, in 1503, lasted just a few hours.

Conclaves have one job: to elect a man as pontiff. The 1378 conclave failed and left a contested title.

The papacy had just returned to Rome after 70 years during which it was based in Avignon, France. An angry Roman mob demanded a Roman pope. The intimidated cardinals obliged. But many cardinals regretted picking the bad-tempered Pope Urban VI and appointed a rival French antipope, Clement VII, who returned to Avignon. A group of cardinals, in a failed bid to end the schism, in 1409 elected a third pope, who was based in Pisa.

An ecumenical council in Germany deposed the successors of all three popes and paved the way for the election of a new, and sole, pope in 1417.

The first conclave in the Sistine Chapel took place in 1492, the year Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic Ocean. The debut election under Michelangelo’s frescoes was marred by scandal. Pope Alexander VI, a member of the wealthy Borgia family known for his lavish lifestyle and many children, secured his election by bribing fellow cardinals with land, money and lucrative positions in the Vatican’s bureaucracy, known as the Curia.

After the Sistine Chapel became the fixed setting for conclaves, cardinals shared sleeping quarters in what used to be Alexander VI’s frescoed apartment in the Vatican.

It wasn’t comfortable. As many as six cardinals shared a room, with makeshift partitions for privacy. Bathrooms were few, and cardinals were given commode chairs, essentially wooden potties, to keep next to their beds.

“It’s a seat with a hole. When cardinals were voting in the Sistine Chapel, staff were coming to clean and to prepare the rooms for the day after,” said Luciano Gagliano, a senior manager at the Vatican Museums, which include Alexander VI’s apartment.

That arrangement continued until 1978, the year of the two conclaves: in August, when Pope John Paul I was elected, and in October, after he died. Polish Cardinal Karol Józef Wojtyła—who would become the next pontiff, and was later canonized as St. John Paul II—was rather horrified by the experience.

“It was a very hot year. Let’s just say they didn’t enjoy staying in these rooms,” said Gagliano. “After the second one, in October, the dream of John Paul II was to prepare a special place for the conclave.”

John Paul II, the first non-Italian pope in 455 years, won after a heated argument between two Italian front-runners helped cardinals’ decision to elect a foreigner, said Melloni, the historian. The Polish pope ordered the construction of a guesthouse for cardinals. The Domus Sanctae Marthae or St. Martha’s House is where all voting cardinals are supposed to be staying during conclaves.

There’s a problem: Pope Francis appointed so many cardinals that there aren’t enough bedrooms. This week, around a dozen of them will be bunking in a nearby building instead.

Write to Margherita Stancati at margherita.stancati@wsj.com

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website