Two jobs, tomato-less gravy: How urban families are coping with food inflation

A look at how people like you -- and your cook and your driver -- are dealing with soaring inflation

What have you cut back on this year?

For some it’s been travel abroad, others are eating out less, or driving the smaller car rather than the SUV.

Shopping for vegetables has become unpleasant, says Anand Dandekar, 40, a landscape designer and father of one.

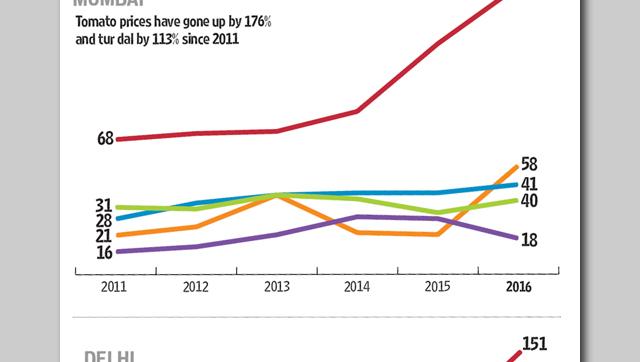

“One week tomatoes cost 40 rupees a kilo; the next, they’ve shot up to 80. It’s as volatile as the stock market,” he says. “It’s not about being unable to pay, it’s about why should we pay these prices? It’s about feeling cheated.”

“In a nutshell, food supply in India is not keeping up with the demand. If your income grows by 6% the demand of non-grains will rise by 9% to 15%,” says Yoginder Alagh, economist and former minister of power, planning science and technology.

As one online meme put it, you can now buy for the same price a kilo of tomatoes or .33 gm of gold.

To keep their savings from being affected, Dandekar’s wife, Pallavi, 38, a teacher, has begun offering private tutorship out of her home, for the past eight months. And where the couple used to take their six-year-old out to a theme park about once every two weeks, they now do these outings once every two months. The Dandekars also switched from a fuel-guzzling SUV to a smaller car, in November.

The lower classes have, of course, been hit doubly hard, since most work in the unorganised sector, where wage increases depend wholly on the whims of their employers.

“As prices have risen, particularly since 2013, many of these employers have decided not to raise the salaries of their cooks, drivers, maids and labourers,” says Abhijit Sen, an economist and former member of the Planning Commission. “Five years before that, the lower classes were seeing an annual rise of about 10%.”

Meanwhile, the prices of essential sources of protein and nutrition like pulses have nearly doubled. To make up for the money spend on food, some are taking on extra work, or switching off the fans to save on electricity bills.

It all starts with effective policymaking and planning at the farm level, says YK Alagh, economist and former agriculture minister. “Right now, farmers are not given sufficient price incentives or adequate market infrastructure.”

Pulses are just one example, Alagh adds. “The average profit margin for those growing pulses in India is negligible. So naturally it is unattractive to grow them,” he says. “Then, to compensate for the lack of supply, pulses are imported from Canada, America and Australia and distributed at a subsidised price. Foreign governments spend hundreds of millions of dollars on programmes to encourage their farmers to export pulses to India. Why do we support other countries’ farmers and not our own?”

(With inputs from Danish Raza)

Read: Why RBI governer Raghuram Rajan is called the inflation warrior

CUTTING BACK

A senior takes on two more jobs

Vatsala Thackeray is 66, arthritic and diabetic, but her work days are only getting longer. Where she used to cook in five homes, she now cooks in seven.

“I took two more jobs in April,” she says. “We have five people to feed at home -- me, my daughter, son-in-law and two grandkids -- and only two of us are earning. Now, my first job starts at 5.30 am and my last one ends at 6 in the evening. I only see my family at 8.”

Back home, lights out is at 9.30. Electricity too is a rationed item and now that the rains are here, the fan is kept off as much as possible.

Vatsala earns Rs 17,000 a month, and her son-in-law, a government school teacher, Rs 20,000. Put together, their earnings used to be enough, with some left over for one trip home to their village every year. That stopped two years ago. As prices continued to rise, they stopped all outings within the city too.

“We haven’t even been to the Siddhivinayak temple in Mumbai since 2013,” Vatsala says. “The whole family never steps out together. How can we? Even train and bus tickets have become more expensive, and our salaries hardly go up at all.”

At home, meal times are now missing the family’s favourite tomato chutney. “How you can spend eighty rupees on one kilo and not make it last at least half a month? These are just tomatoes after all. Even in curries, instead of four per dish, we use half or none.”

Meanwhile, Vatsala’s younger grandson Kaushik, 11, refuses to go out with friends when they plan to eat snacks such as vada pav or misal pav. “He lies, saying there is work at home,’” Vatsala says. “What saddens me even more is that the elder one, Sushant [23], has a BCom degree and knowledge of computers, but hasn’t found a job for a year. How do we escape our economic condition if education does not lead to better jobs?”

As prices annoy, tomatoes vanish from soups and gravies

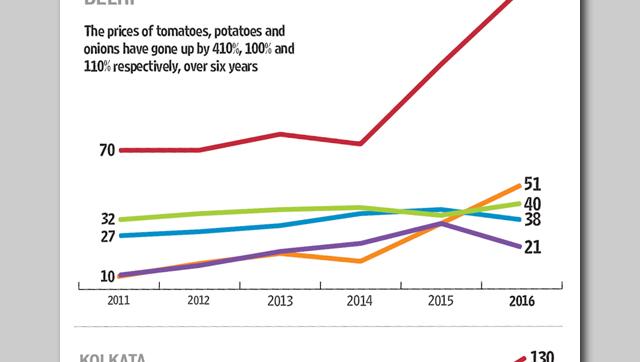

It’s the perfect weather for soup, but the Guptas from Central Delhi’s Karol Bagh have stopped making their favourite tomato broth.

“Ever since the price of tomatoes went up to `80 per kg, I am avoiding tomato-based gravies too,” says Veena, 50, a homemaker and mother of three.

The rising food prices have affected even this upper-middle-class family. They live in a three-bedroom home and have two cars, but have become increasingly conscious of their consumption patterns over the past six months.

“Earlier we would stock pulses and grains in bulk,” says Anil, 51, who owns a car dealership. “Now we are buying only what is required for the week. My wife and I also spend time together planning the weekly menu, keeping the prices of food items in mind.”

What is hurting the vegetarian family the most, they say, are the skyrocketing prices of pulses.

“We make dal for at least one meal. It is nutritious and we are habituated to having it. I still cook dal every day, but due to the price hike I think more carefully about which dal to make more frequently and which ones to skip,” says Veena. “Even so, our monthly food budget has gone up by `4,000 in six months.”

The current government has not taken any steps to improve quality of life of a middle class family like ours, adds daughter Khushboo, 28, a project manager with an NGO. “Prices are rising by the day, but still, more and more taxes are being levied. It’s a vicious circle where the common man is left continuously struggling to achieve or maintain a decent standard of living.”

‘My wife and I might have to move into my mother’s house’

The Chandioks, Ishmeet and Nicola, have been married 10 years and built a good life together.

They live in a rented two-bedroom home in the upscale Lokhandwala area in suburban Mumbai and travelled twice a year — one domestic trip, one foreign. They each run their own catering business, he catering for dogs, she selling cookies, cakes, curries and kebabs out of their home.

Three years ago things started to change. As food costs began to rise sharply, their profit margins began to dip.

“We cut down on travel first,” says Ishmeet, 37. “We decided to do only one trip a year, domestic. Then we started cutting down on eating out; from six to eight outings a month, we now eat out just twice.”

Now, the Chandioks are considering moving into Ishmeet’s mother’s home, which would mean mother, sister, the couple and their three dogs all crammed into a two-bedroom flat.

“Since March, profits have dipped by 15%,” Ishmeet explains. “Our production costs have gone up by 40% in the past year. Sugar, meat and milk are getting more and more expensive, but customers aren’t going to stay if you keep raising your prices. So it’s at the point where our revenue is still rising by about 8% a year, but the hike in expenses is double that.”

For now, the couple is waiting and hoping that prices will stabilise, business will be good again, and they’ll be able to keep their home. “Meanwhile, we shop for kitchen supplies only when there are discounts on offer,” Ishmeet says. “We no longer use tomatoes in our salads. It’s getting ridiculous.”

‘We might cut back on our kid’s classes’

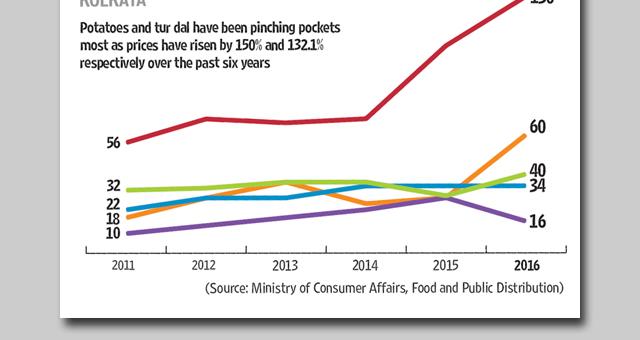

The Sikdars eat more fish than they used to, but that’s only because dal now costs the same, they say with a wry laugh.

Jharna and her husband Sushant migrated from Kolkata to Noida in search of work 12 years ago. She now works as a maid; he as a tailor at an export house. Together, they earn about `15,000, which must support them and their daughter Prijita, 13.

Earlier, the family would eat their favourite fish curry and rice once a week. “But when dal and machchi cost almost the same, who would want to eat dal?” says Jharna, 32. “So now, we compromise a little on quantity but we get a tasty meal. We are still better off than some of our neighbours. We have seen them eating roti with pickle and onion for dinner.”

Dal-roti is no longer a poor man’s meal, adds Sushant, 40. “The way prices are soaring, even middle-class families must be finding it difficult to afford pulses.”

For the Sikdars, it’s the looming toss-up between their daughter’s education and three meals a day that worries them. Prijita is in Class 8 and they spend a total of Rs1,200 per month on her school and after-school tuition. “Her education is very important, but if prices rise any further, we may think of asking her to skip tuitions. That will save us Rs 400 per month,” Jharna says.

Read: An open letter to the finance minister from the salaried class

Watch: People in Delhi discuss how inflation has messed with their household budgets