The rise of Anywhere City

Generic globalised architecture is erasing the memory, identity, and character of Indian cities

Gurugram’s skyline glints with mirrored facades, soaring office towers, and luxury condominiums—symbols of aspiration in a globalising India. But to many long-time residents, such as Rajesh Bhardwaj, the city’s transformation feels oddly disorienting. Visitors often tell him it reminds them of Dubai. “And I wonder why that is a compliment,” he asks. “Shouldn’t Gurugram feel like Gurugram?”

Across the country—from Bengaluru and Pune to New Town Kolkata, Chennai, and Hyderabad—a similar story of uniformity is unfolding. Cities are morphing into indistinguishable zones of glass-and-steel high-rises, all derived from the same architectural catalogue.

At first glance, you could be in Dubai. Or Singapore. Or anywhere, really.

What’s vanishing in the process, say architects and urbanists, is more than just variety in form. It’s the character of a city, its memory, and cultural grounding.

“Globalisation has undoubtedly expanded the architectural imagination in India,” says architect and urbanist Dikshu Kukreja. “But in our pursuit of a global visual language, we are rapidly losing the nuances that define our cities. Architecture must be rooted—not just in place-specific design, but in memory, community, and climate. When every city begins to resemble another, we risk erasing the very distinctiveness that makes each Indian city unique.”

Architect Manit Rastogi shares the concern. “We’re witnessing the erosion of place-based design. Architecture is becoming a universal product—exportable, scalable, but often contextually irrelevant,” he says. “The essence of place isn’t just about looks—it’s about how people inhabit space, how buildings respond to their environment, and how cities tell their own stories. That narrative is fading fast.”

When Indian skylines changed forever

Following economic liberalisation in 1991, the influx of global corporations—especially in finance and IT—created a huge demand for new office spaces: open-plan layouts, climate-controlled towers with glass curtain walls, large floor plates, and flexible work zones tailored for multinational needs. Architects responded with glass-and-steel aesthetics inspired by cities such as New York, London, Hong Kong, and Singapore, marking a sharp departure from traditional Indian forms.

The late 1990s and early 2000s saw the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZs), accelerating the construction of steel-and-glass towers. Mumbai, India’s financial capital, led this transformation with early examples in Nariman Point and later, the Bandra-Kurla Complex (BKC). The trend soon spread to Bengaluru, Gurugram, Hyderabad, and Pune.

Today, in Bengaluru, glass-and-steel towers dominate areas such as Yeshwanthpur, Hulimavu, and the Outer Ring Road. Pre-globalisation, Hulimavu’s lush greenery and village-like charm defined South Bengaluru. The ORR was a quieter corridor with bungalows and small businesses. In Pune, Hadapsar and Hinjewadi—now home to high-rises like Amanora Gateway Towers and Blue Ridge Towers—once had smaller settlements with traditional wadas dotting the landscape.

Chennai’s OMR (Old Mahabalipuram Road), now a massive IT corridor, was a coastal stretch of fishing villages and paddy fields. Kolkata’s New Town was made up of wetlands and rural hamlets. These transformations, driven by what experts call “impatient capital”, are erasing vernacular architectures—Bengaluru’s tiled-roof homes, Pune’s courtyard wadas, Chennai’s Indo-Saracenic facades, and Kolkata’s colonial bungalows—replacing them with homogenised buildings that prioritise profit over cultural memory.

“In fact, one of the key drivers behind the homogenisation of our cities is the tyranny of images in the age of globalisation,” says Rahul Mehrotra, architect, and professor at Harvard University’s Graduate School of Design. “These often-compelling images circulate rapidly on social media, generating new imaginaries of urban form. Gurugram wants to be like Dubai, Mumbai aspires to become Shanghai, and Pune seeks to emulate Mumbai—ambitions of becoming part of a global network through the production of glass-clad high-rise buildings.”

Dubai and Shanghai, adds Mehrotra—also the author of several books, including Architecture In India Since 1990— represent the “landscapes of impatient capital.” Capital, by nature, is impatient—it demands quick returns. This fuels the rapid construction of high-rise towers that can maximise returns. It’s not architects, but real estate developers and investors who are impatient for these returns, he says.

His point is supported by architect-author Goonmeet Singh. “We are living in an era of capitalism that thrives on international trade—a system that prefers a shared value system and a predictable built environment. Many multinational corporations setting up offices in India simply replicate the architectural templates they’ve followed in their home countries, with little regard for local context.”

Architecture, says Singh, reflects the social and cultural realities of its time. “The average architect doesn’t see himself as the custodian of the city’s architectural narrative—he’s simply responding to the client’s brief.”

India’s rich architectural traditions

India’s architectural traditions are among the most diverse in the world, shaped over millennia by geography, climate, religion, and cultural exchange. If Mughal architecture blended Persian symmetry with local motifs, colonial rule introduced Gothic, Neoclassical, and Indo-Saracenic styles—grand buildings like the Victoria Memorial in Kolkata and Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus in Mumbai being prominent examples.

After Independence, a new generation of architects sought to define a modern Indian identity grounded in climate, culture, and social equity. BV Doshi and Charles Correa were at the forefront of this movement. Doshi’s IIM Bangalore (1977) drew from traditional courtyard layouts to create a campus responsive to climate and conducive to community interaction, while Correa’s Jawahar Kala Kendra (1992) in Jaipur integrated traditional Rajasthani motifs with functional, modernist spaces. In Delhi, Raj Rewal’s Asian Games Village and the Hall of Nations (demolished in 2017 for redevelopment of Pragati Maidan) reflected a bold attempt to blend modernity with cultural depth.

“Charles Correa used to say architecture is not a movable feast—it is rooted in climate, culture, lifestyle, and material. He challenged the modernist maxim ‘form follows function’ by asserting instead that ‘form follows climate,’” says Mehrotra.

However, this rich architectural plurality is now threatened as globalisation continues to privilege homogeneity over heritage. The nuanced grammar of jaalis, courtyards, verandas, and stone plinths is giving way to generic high-rises designed for speed, profit, and global appeal.

“India has historically been home to cities like Shahjahanabad—planned, compact, and deeply attuned to human scale and climate. These were cities designed around pedestrians, public spaces, and natural systems. In contrast, our urban environments today are evolving at an unprecedented pace. Their role has shifted significantly—from walkable community hubs to high-density, service-driven centres shaped by global capital, rapid infrastructure expansion, and the pressure of scale,” says Rastogi.

“Urban planning today,” he adds, “often prioritises economic efficiency and infrastructural output over more nuanced considerations like inclusivity, equity, and environmental resilience.”

Kukreja argues that it’s not a lack of knowledge but of conviction. “Everyone across the ecosystem—from architects and developers to clients and governing bodies—has a role to play. Many traditional principles, evolved over centuries, offer simple, elegant solutions to complex climatic challenges. Yet, in the rush for speed, spectacle, and perceived contemporaneity, they are either forgotten or treated as decorative afterthoughts.”

The cost of homogenisation

The cost of architectural homogenisation, says Rastogi, goes far beyond aesthetics. “When design becomes detached from its context, we risk more than just visual monotony—we begin to erode cultural memory, compromise environmental performance, and create spaces that feel alien to the very communities they are meant to serve.”

Across many Indian cities today, we see the effects: public spaces are diminishing, local materials and techniques are being overlooked, and architecture is increasingly treated as a commodity—stripped of its ability to reflect identity or foster belonging, he adds.

Kukreja says that when cities lose their distinctiveness, their people lose a part of their identity. “Architecture is a living archive—it tells us who we are, where we come from, and how we live together. Homogenisation creates visual fatigue and cultural amnesia.”

“Mumbai once had a richly layered architectural identity. Ballard Estate’s neoclassical buildings contrasted with the Art Deco homes along Marine Drive. But the introduction of the Floor Space Index (FSI) in 1964 triggered a flattening effect, with blanket bylaws imposed citywide. This dissolved architectural distinctions, contributing to the erosion of cultural memory and local identity,” says Mehrotra.

AK Jain, former commissioner (Planning), Delhi Development Authority, highlights lessons from the Capital’s urban planning experience. “In the 1970s, Connaught Place area saw high-rise developments influenced by the zoning provisions of the Master Plan for Delhi 1962. However, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, concerned about the aesthetic and functional impact of these structures on Lutyens’ Delhi, intervened. This led to the formation of the New Delhi Redevelopment Advisory Committee in 1972, which recommended a three-dimensional approach to the Delhi Master Plan, moving beyond two-dimensional land-use zoning to consider height, volume, and urban form.”

The committee also proposed the establishment of the Delhi Urban Art Commission (DUAC) in 1973, which has since played an important role in ensuring that Lutyens’ Delhi’s heritage and low-density character is preserved. “Cities must adopt three-dimensional master plans that prioritise context-sensitive architecture and urban design to maintain their unique identity,” Jain says.

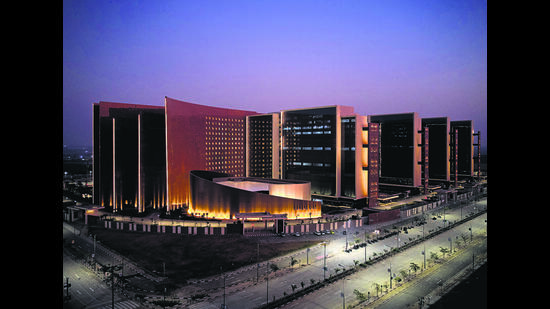

Indian cities are at a crossroads, says Rastogi, who is also the architect of the Surat Diamond Bourse. “We have the opportunity—and the responsibility—to create a new kind of architecture that is globally benchmarked in terms of performance, but deeply rooted in place, culture, and climate.”

The Surat Diamond Bourse—now the world’s largest office building, spanning 7.1 million square feet—embodies this philosophy. While its scale is global, the approach is contextual. “Surat’s hot and humid climate called for a passive, efficient, and socially responsive solution—but just as importantly, so did its cultural and economic identity,” he says.

“I believe it is the responsibility of all stakeholders—architects, urban planners, city authorities—to come together to reverse this trend of architectural homogenisation, which threatens to erase the unique identity of our cities,” says Goonmeet Singh.

“At its core, architecture is a narrative of place. It must engage not just with how a structure looks, but how it performs, how it adapts, and how it contributes to the larger urban ecology,” adds Rastogi. “Design that is rooted in place can be both contemporary and resilient. It helps us build not just for today, but for the future. The challenge is to integrate global efficiencies with local sensitivity—so that as our cities grow, they continue to feel like they belong to us.”

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website