What the virus cost us: 5 years on, Roshan Kishore writes on the pandemic impact

The Indian economy contracted (by 5.8%), for the first time in four decades. The road to recovery is littered with new roadblocks. We are still paying the price

How did a once-in-a-century pandemic impact the Indian economy?

The most mechanical or rather dehumanised way to answer this question would be to say it triggered an annual economic contraction (of 5.8%) — the first in four decades — thereby derailing future economic growth to sub-par levels for a considerable period. (See Chart 1)

A more nuanced answer requires looking at the economic data in greater detail and flagging multiple trends which delineate the pandemic’s economic impact across class, sectors and various stakeholders in the Indian economy.

Even in the immediate aftermath of the pandemic, its disruption was not the same across sectors. Sectors such as agriculture did not face any lockdown-like conditions. Operations were almost completely uninterrupted. Contract-intensive services, meanwhile, suffered the most. This shows up clearly when one looks at the detailed break-up of Gross Value Added (GVA), which is GDP minus subsidies and taxes.

Agriculture had an annual growth of 4% in 2020-21 while the trade, hotels, transport, communication and broadcasting services part of the services sector contracted by a massive 20% that year.

Not all service-sector activities were affected equally. If one were working in the financial markets or with a software company, the pandemic caused very little disruption once companies figured out how to work remotely.

Both workers and companies made or lost their fortunes depending on how affected and disrupted their sector was by the pandemic. A relatively poorly paid IT professional who could switch to work-from-home was more likely to emerge from the pandemic with very little financial scarring, while a restaurant owner whose business was booming pre-pandemic but contingent on footfall, particularly in a tourist or business district, would have seen the business devastated.

***

The overall impact was eventually shaped by class than sector.

The rich, with much less impact on their overall financial health, accumulated what have now been described as forced savings. Even if money was not a problem, they could not spend on activities such as travel and tourism, new cars or even eating out, because of supply chain disruptions. The war in Ukraine and China’s zero-Covid policy much after the rest of the world had eased restrictions added to these supply chain disruptions, altering habits over a longer term.

The poor, on the other hand, had to resort to loans to fund even basic requirements. Many had to shift children from private to government schools as incomes dwindled; borrow money from predatory lenders at exorbitant rates; and move from non-farm to farm employment even if it meant very little money in hand.

To be sure, a lot of the (relative) spending to support the consumption of the poor was in the form of higher government deficits. The fiscal deficit spiked sharply in the aftermath of the pandemic and is still in the process of being gradually brought down. (See Chart 2)

What the fiscal support gave to the economy was perhaps taken by monetary tightening once the worst of the pandemic was over. The Reserve Bank of India has just started the pivot towards reducing interest rates. The relief from this pivot will take some time to materialise through the transmission effect channels in the system.

***

How have the initial differences in the disruptions of the pandemic affected the economy in the years since things normalised? Post-pandemic growth numbers had an artificial boost to them because of pent-up demand from the pandemic years.

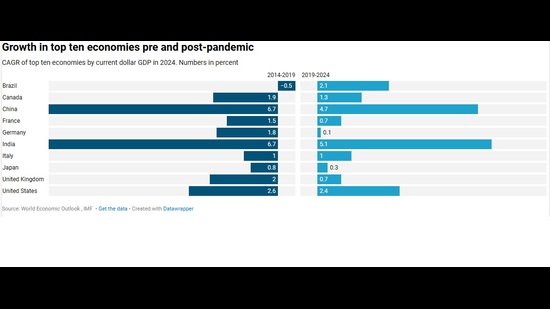

The best way to understand this is by looking at the annual growth numbers in the economy along with the compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from pre-pandemic levels. The former has started losing momentum as the latter catches up, with what can be described a long-term trend growth rate for the Indian economy.

To be sure, this is not to suggest that the well-off part of the Indian economy is losing momentum in a big way. Income-tax collections, a bellwether of formal sector labour incomes, continue to grow at a robust pace and views are still bullish on the premium segments of the consumer economy.

What has happened, however, is more on the lines of a rationalisation of the growth momentum. Once someone has bought the car they wanted to but could not get because of delayed supplies, they are unlikely to do this again for some time.

For the poor, the path to upward mobility is still proving to be a steep one. These segments have started moving from villages back to cities and from unemployment to employment, but this road is still littered with new roadblocks such as unpaid self-employment rather than rewarding salaried work.

Between their own incomes and growing support from the government, they have perhaps just enough to buy food, but not enough money to spend as they would like to on things such as clothing. This is one of the reasons India continues to be a high food inflation but low core inflation (non-food, non-fuel) economy, despite growth losing momentum relatively, compared to pre-pandemic levels.

***

The biggest change from the pre-pandemic era, although not necessarily because of the pandemic, has been in the world economy.

Advanced economies, with the US leading the way, are much more protectionist and mercantilist today than earlier. Geopolitics is significantly more turbulent than at any time in the last half-century. China, despite what looks like an irreversible slowdown in its growth, is sitting on massive overcapacity.

Will all this strengthen or weaken India’s chances of gaining from the China+1 sentiment -- driven by the desire among large multinationals to derisk their manufacturing from the jolt it suffered during the pandemic, when suppliers or manufacturing partners in China stopped or slowed production -- to boost its long-term growth? (See Chart 3)

It will take an alignment of multiple proverbial stars for this to happen. Private investment will have to gain momentum. This will not happen until businesses are bullish about future demand. The government is hoping to push more reforms to facilitate this. It is also asking businesses to share more with their workers, to stimulate demand.

Then there is the question of exploiting our already diminishing demographic dividend opportunity.

The key takeaway is clear. The pandemic’s macabre spectre is now behind India -- but economic policy must get its act together to deal with a host of new, once-in-a-lifetime challenges for the nation.

(roshan.k@htlive.com)

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website