It’s not just that the heat could kill you: A Wknd interview with author, researcher Jeff Goodell

His latest book is an attempt to make this abstract threat more visible. “It wasn’t easy. It was like writing the biography of a ghost,” he says.

“I’m looking out of my closed window, and I have no idea how warm it is out there. It could be 30, 32 or 35 degrees Celsius,” says Austin-based journalist and author Jeff Goodell.

This is unlike, say, a typhoon or hurricane, he adds. Trees sway, there is heavy rain and flashes of lightning. “When it comes to heat, there are virtually no visual cues.”

Even he, a climate reporter for over two decades (with stories in The New York Times, CNN and The Guardian, among others), never really paused to acknowledge how dangerous heat is. This changed in the summer of 2018.

He was in Phoenix, Arizona, where temperatures had breached 40 degrees Celsius. He was late for a meeting, couldn’t find a taxi, and decided to run instead, as he sometimes does.

“By the time I had gone five blocks, I was dizzy. My heart was pounding. I could sense that if I pushed myself, I’d be in trouble,” he recalls. “That was the first time I realised that heat isn’t abstract. It can quickly become lethal, even for a healthy person.”

It struck him then, he adds, that as our planet was warming, we weren’t adequately afraid, alert to, or bracing for this threat we cannot see.

What could we be doing differently?

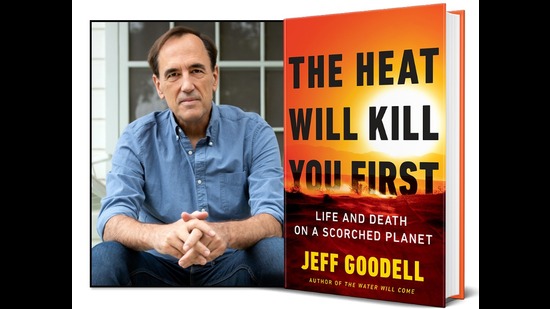

He chased that question for five years and, in 2023, released his findings in the form of a book. His sixth climate-themed work, this one was titled The Heat Will Kill You First: Life and Death on a Scorched Planet.

In it, Goodell traces how heat has quietly shaped our world. Drawing on scientific research, field reporting and the lived experiences of victims, he explores the biology of heat stress, the failures of our built environments, the unequal burden on vulnerable communities, and global attempts to adapt.

At its core, the book is an urgent attempt to make heat visible, and it wasn’t easy, he says. “It was like writing the biography of a ghost.”

It’s not just that heat can kill you, though there is that, of course. It also leads to higher rates of miscarriages, lower test scores. “We’re only beginning to understand the range of consequences,” Goodell adds. “The good news is there are ways to protect ourselves, and to adapt. Some communities are already doing it.”

Excerpts from an interview.

* What makes us so blind to heat as a fatal threat?

I think there’s this tendency to think, “Oh, we’ve faced 40 degrees Celsius before. We can get through it” or “It’s just a couple of degrees hotter than usual, isn’t it?”

Because the change has occurred over time, there’s a shifting baseline syndrome at play. It’s very hard for us, in our daily lives, to recognise and remember how each small, incremental change has added up.

That’s why science is so important. It is able to tell us: “No, in fact, it hasn’t always been this way.” Or, “Even if we’ve faced 40 degrees Celsius before, it wasn’t over such an extended duration.”

* You’ve said our inability to understand heat as a problem is also a factor of how we view it, talk about it, and regard it in our world.

Yes. “Hot” is viewed as cool, sexy. Sweat is seen as purifying, and a sign of inner strength. Warmth is comfort, and safety.

Often, in movies, books and even weather forecasts, especially in the West, the idea of a hot day is accompanied by images of people heading to the beach, taking the day off, children playing in sprinklers. Heat is portrayed not as a threat but as this engine of leisure.

And yet, the majority of people, in the US and in India, are being forced to make a choice between going to work where they must put their lives at risk from extreme heat, or staying home and losing wages.

Meanwhile, we’re simply not building cities with a sense of public good anymore. There aren’t enough green spaces. There isn’t enough access to water, affordable electricity, or insurance that allows one to get paid when one can’t pursue one’s outdoor livelihood.

These factors are all tied together by the lack of political will and leadership.

* What are the measures governments should be considering, today?

The changes don’t necessarily need to be big ones. In Austin, for instance, some bus rides are free even on just very hot days.

Freetown, the capital of Sierra Leone, is building heat-reflecting shades over outdoor markets.

In longer-term changes, Athens plans to renovate an ancient aqueduct dating to 140 CE, that will help bring more water into the city and create cooling ponds that people can access.

In India, the organisation SEWA (Self-Employed Women’s Association) is testing a microinsurance programme that offers insurance and direct cash payments to women in the informal sector, when heat waves occur and they can’t make it to work.

A key part of heat preparedness is also the messaging. Spain and Greece are naming and ranking heatwaves, in the way we do for hurricanes and cyclones, so that people are more aware.

Getting this kind of message out is especially important in regions where it has traditionally been hot and there is this sense that “we’ve seen this before”. It is up to the government and the media to reinforce the message: “No, we haven’t.”

* If you could do anything, to effect change in this area, what would it be?

If I could wave a magic wand, I’d give every region a mayor or leader who cares deeply about climate change.

I would also subsidise access to electricity and air-conditioning. Air-conditioning is not the solution, and it is problematic, but there are about 750 million people in the world that still lack electricity.

I would also set up more solar panels, so people are not dependent on a grid that is already struggling and can easily falter.

Heat is a really complex issue. It’s not like curing a disease. There is no vaccine or pill.

It will be crucial to learn from each other.