UP’s parched hamlet now dreams of running water

People in Pathramani, a village in the state's Bundelkhand, have gone to astonishing lengths to get water. A majority refused to vote in Uttar Pradesh’s 2017 state and 2019 national elections as a mark of protest.

A little-known village in Uttar Pradesh’s Bundelkhand, one of India’s driest and poorest regions, reveals an India that has all but disappeared.

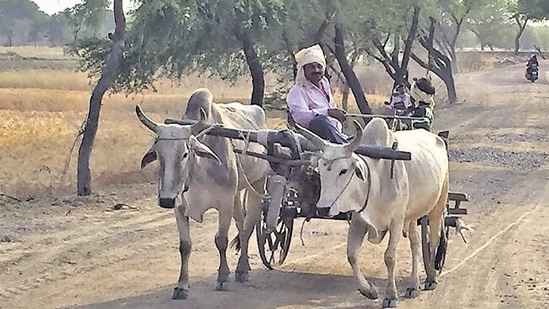

The village, Pathramani, still doesn’t have a paved road. Rust-red hillocks and boulders leading up to the village resemble pictures of a Mars’ landscape sent by NASA’s rover. Bullock carts ply on its dusty roads and most people live in low-roofed mud houses.

People here have gone to astonishing lengths to get water. A majority refused to vote in Uttar Pradesh’s 2017 state and 2019 national elections as a mark of protest, a fact corroborated by the district administration of Chitrakoot, in which Pathramani falls.

Chitrakoot is no ordinary place. It is where Hindu god Ram spent 11 of his 14 years in exile, according to the epic Ramayana.

In the recent state elections, voters did participate in the ballots as signs of water supply work emerged.

Despite the rains it gets every monsoon, the hamlet is mostly dry because its impermeable terrain doesn’t allow rainfall to seep into the earth, necessary for aquifers. A few ponds have water that is undrinkable, salty and contaminated.

People shouldn’t be growing wheat at all since it’s a water-hungry crop, but they still do, irrigating their land with the contaminated water.

Life is miserable. Lack of water means few outside the village are keen to marry off their daughters to Pathramani’s men, as the drudgery of fetching water from far-off sources falls on women.

“It’s been this way as far back as I can remember,” said 62-year-old resident Ram Baran Singh. The water department provides drinking water through tanker lorries, but they are never enough.

During harsher conditions, authorities have issued orders in the past prohibiting the use of water provided by lorries for non-drinking purposes. “I feel itchy after bathing in the contaminated pond,” says villager Lokesh Yadav. People here often get stones in their kidneys due to lower water intake, said an official, requesting anonymity.

Like others, Singh is anxiously waiting for a dream to become reality: a functional water tap at his doorstep. If the state’s deadline for the job is met, parched homes in this Bundelkhand region should get water by September 2022.

At roughly 47%, India is nearly halfway through the ambitious programme – Jal Jeevan Mission (water is life) – to make available tap water in each one of India’s 190 million rural homes.

The programme was launched by the Narendra Modi government in 2019, with a deadline of 2024, while Uttar Pradesh officials say parched belts of Bundelkhand will get tap water by September this year. The scheme is likely to be a talking point for his Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in that year’s national elections – water is a precious commodity, piped water even more so, and there are still many villages that suffer for lack of it.

In Pathramani, the pipes are being laid. In nearby Dugua, a tank that can hold 175 kilolitres is nearing completion. Some 50km away lies the source that will supply the villages: an intake well in the Yamuna river.

“The physical progress so far is 70%. We are monitored by higher authorities three days a week. We are confident of adhering to the deadline,” additional district magistrate Sunandu Sudhakaran said.

Residents, who face a daily water crisis, don’t easily buy these assurances. “What if engineers leave all this incomplete?” asked villager Ramesh Kumar.

But despite Uttar Pradesh lagging many states in the Jal Jeevan programme – covering some 13% of its 26 million households, according to real-time data on a centralised dashboard – the progress has been significant. As officials point out the incremental coverage marks a 145% increase in the number of households with piped water since the scheme’s launch in 2019 (it excludes households which already had water taps under previous schemes).

The focus, the officials add, is on the driest parts, which are also geographically the most challenging to connect to a water source.

A federal review last year asked the state to give “undivided focus on coverage of priority areas, i.e. water quality affected habitations, drought prone area, eight Aspirational and 20 Japanese Encephalitis affected districts, Scheduled Castes/ Scheduled Tribes majority areas and Saansad Adarsh Gram Yojana, etc”, according to an official document.

Jal Jeevan is critical national project because nearly 820 million people in 12 major river basins of the country face high to extreme water stress.

Getting to a water source is a long haul in rural India. In Jharkhand, it takes women 40 minutes one way, without taking into account the waiting time, according to a National Sample Survey Organisation survey. In Bihar, it’s 33 minutes. Rural Maharashtra clocks an average of 24 minutes and Uttar Pradesh 38.

So why is water scarce?

Bundelkhand has a recorded annual average rainfall of 1,000mm, mostly in July and August, according to Dalchand Jhariya, a geologist from the National Institute of Technology, Raipur.

The “high intensity of rain scarcely leaves any time for the water to infiltrate to the soil” while degraded forest cover inversely affect water infiltration and groundwater.

“This itself causes the unusually high water run-off rate gushing towards the north, creating deep gorges and rapids because of the Vindhyan plateaus flanked by high cliffs.”

High summer temperatures, sometimes nearing 50 degrees Celsius, cause quick evaporation in ponds.

From a water source, usually a river or a dam, to a household, it takes over 23 physical structures to get water flowing, said supervision engineer Dhruv Shukla.

“To lay pipelines, we have had to blast our way through hard rock,” said Shukla. His job is to coordinate task outsourced to major firms, such as Larsen and Toubro and GVPR Engineers.

The Bundelkhand region, spread over 70,000 sq km in 13 districts of Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, faced a non-stop drought between 2003 and 2010, decimating farming and setting off waves of out migration.

Seven of Bundelkhand’s districts lie in Uttar Pradesh: Chitrakoot, Banda, Mahoba, Hamirpur, Lalitput, Jhansi and Jalaun. All of them are parched. It’s, however, Chitrakoot, which poses an uphill task because of its topography.

The rockier the terrain, the costlier and more challenging the task. In this part of the region, provisioning tap water to slightly over 100,000 households in 461 villages will cost ₹1,132 crore, according to the district official quoted above.

Last week, the Centre released a fresh tranche of ₹2,717.62 crore to Uttar Pradesh for the tap water mission.

The Jal Jeevan Mission’s goal is to provide drinking water. That will end a lot of suffering but not larger economic woes.

“Agriculture needs water. Industry also needs water. So, Bundelkhand suffers on both counts,” said Girish Sharma of the Dewas-based non-profit Samaj Pragati Sahayog.

By September, that could change.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website