The making, unmaking and remaking of Mehar Chand Market

The story of the making and unmaking and the possibility of remaking of the Mehar Chand Market has been full of turns, both fortuitous and fateful.

As Ashok Sakhuja, 65, walked the desolate corridors of the once-bustling Mehar Chand Market in Lodhi Colony, he explains to the curious shopkeepers the provisions of South Delhi Municipal Corporation’s (SDMC) redevelopment plan for the market. A day before, on Tuesday, the SDMC had approved a long-pending plan to redevelop Mehar Chand Market as a modern three-storey pedestrian-only shopping plaza, with a uniform look for all shops. The existing shops will be demolished and reconstructed by the traders in accordance with the sanctioned building plan.

Sakhuja, the president of the market association, tells shopkeepers to get ready to raze and rebuild their shops. “Our market has had many ups and downs. This time, we are determined to ensure that MCM joins the league of CP, HKV, Khan, ” says Sakhuja, turning his attention to us.

By Khan, he means Khan Market, by HKV he means Hauz Khas Village—and by MCM he means his own Mehar Chand Market. “By 2014, we were almost there; in fact, we were the hottest design destination in the town. THT Gifting by JJ Valaya, Pia Pauro , Masaba Gupta, O Layla, they were all here and then they all left,” says Sakhuja, whose father was among the refugees from Pakistan who were allotted a Khoka (a wooden makeshift shop) in the market post-Partition.

The story of the making and unmaking and the possibility of remaking of the Mehar Chand Market has been full of turns, both fortuitous and fateful.

It goes back to 1948, when about 240 makeshift shops were allotted to refugees from Pakistan, on the fringes of the Lutyens’ Delhi. In 1963, the government built 152 concrete shops, and what was initially known as the refugee market was remanded Mehar Chand Market after Mehr Chand Khanna, the then Union minister for rehabilitation. Those days, shopkeepers paid about ₹18 a month as licence fee to the government.

In the mid-1960s, while most people continued with their old business in the newly built market — grocery stores, cycle repair shops, tent rentals — Gurucharan Singh, one of the allottees, set up a tailoring shop, calling it ‘Eight Wonder’. Initially, most of his customers were from nearby colonies wanting him to alter their old cloths—a job he did with great finesse. His tailoring enterprise soon began to attract customers from far and wide, and soon the other shop owners hired tailors – a lot of them were from Darjeeling– and started their own tailoring businesses. In the next few years, the market had over 60 shops with the ‘Wonder prefix’—First Wonder, Second Wonder, Third Wonder, and so on.

The Mehar Chand Market became famous as the ‘Wonder Market.’

“Those were the days when readymade revolution had not taken off and it was common for children to wear their parents’ clothes; if they required alterations they would come to us. This was the only market in the city where tailors had the ability to turn the bell-bottom into a waist, and the waist into a bell-bottom,” says Nand Kishor, who runs 1st Wonder. Started in the 1960s, this is one of the four surviving tailors in the market. “Many people still come here for alterations; they want to wear their grandfather’s and father’s coats on certain occasions. ”

In the 1970s, the old-timers say, the market also became popular for its Dhabas. “It was a food destination in central Delhi much before Pandara Road, attracting many young people looking for affordable meals,” says AK Jain, an architect and former commissioner (planning) at the Delhi Development Authority, and the author of many books on Delhi. “I think the market could never compete with its neighbours such as Khan Market because it catered only to those living in the government colonies, who did not have great purchasing power. What also did not help was that the market had only one entry point,” added Jain.

But that changed in the 1980s, a period that marked the first major shift in the market’s fortunes. The Asian Games, the shop owners say, brought development to the area, with Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium and many government offices, including CGO complex coming up in the vicinity.

“The wide road, the footpath were all developed during this time. Many owners renovated their shops, dabhas were converted into proper restaurants, a few sports shops also came up. For the first time since its inception business got a boost in the market and our income increased significantly,” says Praveen Kumar, who runs a grocery shop in the market. “We got a new clientele, a lot of them young sportspersons and government officials from different parts of the city,” says Raman Juneja of Juneja’s Restaurant, one of the few surviving eateries in the market from the 1970s-80s.

Over the next two decades, as the readymade clothes became popular, many tailoring shops shut down, giving way to shops selling sweets, mobile phones and accessories, garments and salons, etc. “The increasing income and the rise of readymade clothes business killed the alternation business,” says Vinod Arora, another surviving tailor in the market. “The closure of the tailoring shops meant the market lost its USP and was forgotten.”

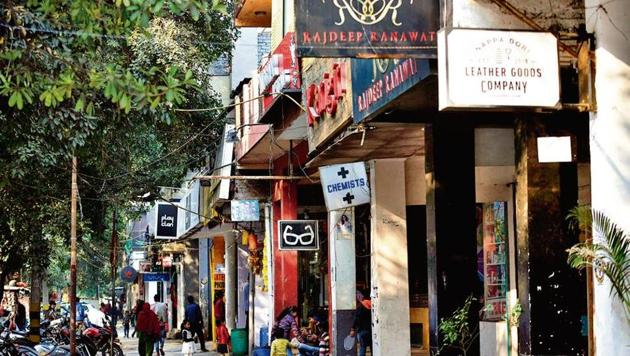

Then, in 2007, Café Coffe Day opened an outlet in the market, marking the beginning of its makeover. Over the next couple of years CMYK Book Store, Soma , Fab India, Kunafa came. By 2014, half of the market’s 152 shops were taken over by designer boutiques, fancy restaurants, trendy cafes, European-style brasseries jewellers, high -end salons, making it a hot destination for designer brands and products.

Mehar Chand Market was now giving Khan Market, its vaunted neighbour, a run for its money, what with the fact that latter had ran out of space, and went out of reach for many because of the astronomical rents. “Back then everyday I would show a dozen people, mostly designers, shops available for rent in the market,” says Inderjeet Singh, 63, who runs a property business in the market.

The owners were pleasantly surprised by the sudden interest in the market and the transformation it was undergoing. Many of them exited their decades-old- businesses and rented out their shops. The going rate for a 400 sq ft shop for sale was about ₹12 crore in 2014, while the rent for a shop of the same size jumped from ₹40,000 in 2010 to ₹2.5 lakh per month by 2014. “ We moved there because the location was great and the rent was affordable. But soon the owners became greedy and began to raise the rent, wrongly believing that Mehar Chand market had become a Khan market. The fact is the footfall in the market never matched the hype, but owners did not understand this,” says Pramod Kapoor, founder Roli Books, who started CMYK bookstore in the market in 2010 and left in 2018.

Agrees Nitin Mehta, head, retail and logistics, Playclan, a design store, one of the first to arrive in the market in 2009: “The market attracted a lot of NRIs and expats, who found the place quiet and quaint, without parking problems. But the footfall and sales were not enough to justify the high rents. This was our flagship store and we tried to make it viable, and stay put but eventually it did not work,” says Mehta, whose firm exited the market in May this year. “Our shop in Khan Market is three times smaller in size, but generates three times higher sales.”

In 2018, about 135 basement and first floors shops were sealed by SDMC, on the directions of a Supreme Court-appointed monitoring committee, as only the ground floor was permitted in the market as per its original plan, but shopkeepers had built additional floors over the years.

The sealing drive seemed to have sealed the fate of the market for good, with dozens of brands exiting it in the past two years, including bigger ones such as Fab India, which was spread over three floors and served as an anchor store. Today, about over 50 ground floor shops are permanently closed, with stickers ‘For Rent’ pasted on them, their colourfully painted fronts the only sign of the market’s glory days.

“The sealing was a final blow. I admit that a lot of owners could have been more reasonable in their demands, and we as an association could have done more to promote the market,” says Sakhuja as he a makes a list of people he needs to visit and thank for paving way for the redevelopment of the market. “We have learnt our lessons. After the redevelopment, we will ensure that market is run like a well-managed mall. I can assure you that MCM’s story will have a happy ending.”