Tata-Mistry spat: How independent are independent directors?

Happenings in several Indian companies over the years have also shown that the behaviour of even some of those that meet the criteria is not always independent. In some cases, entrepreneurs and promoters nominate former bureaucrats who have done them favours in the past as independent directors

I read the news today (oh, boy): Charges and counter-charges continue to fly in the Tata-Mistry spat; the demonetisation debate continues to spawn economists faster than the Reserve Bank’s presses can print new currency or the government can change rules; and the temperature in and around the North Pole is 20 degrees Celsius higher than it should be now.

The last is the most worrying. As a result of higher temperatures in the Arctic, the amount of sea ice that has formed so far this year – it usually starts forming in November, as winter arrives – is the least ever, lower than the previous low in 2012 and much lower than the 30-year average.

Tempting as it is to write on this, or on the other two topics, I’ve chosen not to (at least, not directly).

If anything, the Tata-Mistry fight and the demonetisation drive have only highlighted the perils of instant analysis (and equally instant outrage).

Almost four weeks after the demonetisation of Rs 500 and Rs 1,000 banknotes, the long-term impact of the move is still unclear. As Mint’s Niranjan Rajadhyaksha wrote in a column: “The real puzzle is what this means in the long run. Much depends on whether this exogenous shock alters citizen behaviour—in terms of whether less cash will be used in the future, whether the tax base will expand as more transactions are done through the formal financial system and if other policy measures restrict the creation of fresh black money.”

Read: Currency reform: a risky natural experiment

Do note that his use of long run is different from that of former Prime Minister Manmohan Singh who, in a speech on the demonetisation issue in Parliament, channelled John Maynard Keynes and said: “In the long run we are all dead.”

This is what Keynes said in the same piece – aptly enough, it was on monetary reform – the more famous quote is from: “But this long run is a misleading guide to current affairs. In the long run we are all dead. Economists set themselves too easy, too useless a task, if in tempestuous seasons they can only tell us, that when the storm is long past, the ocean is flat again.” Rajadhyaksha’s conclusion is that there will be fundamental changes because of demonetisation – only we don’t know what they will be.

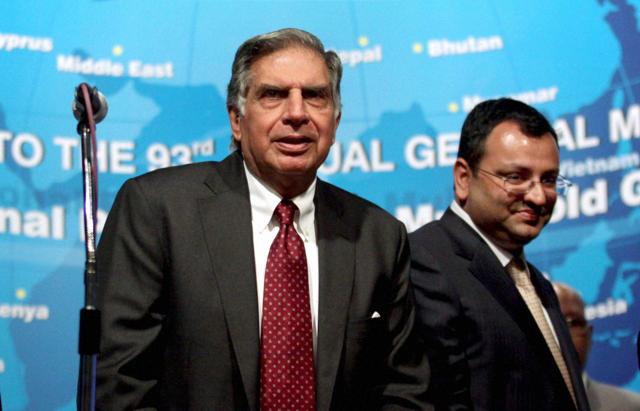

And a month after Cyrus P Mistry was suddenly and shockingly removed as chairman by the board of Tata Sons Ltd, the two sides seem reconciled to a long and messy fight involving shareholders and, possibly, the courts. It is still not clear why Tata Sons fired Mistry. Nor is it clear what Mistry hopes to achieve by prolonging the fight. The independent directors of the various Tata companies have been thrust into the fight. Some are willing participants; others, not so. Over the next few days and weeks and months, they will find their roles in this fight called into question – and that is why I have decided to write about the independence of independent directors.

The Companies Act 2013 has an elaborate definition of independent directors. If companies were to follow Section 149 (6) of this law in letter and spirit, then they would have to declare that most of the independent directors on their boards are, in fact, not really independent. For instance, after the appointment of former Infosys Ltd chairman N R Narayanamurthy’s relative DN Prahalad to the board of the company, one proxy advisory firm said he seemed more like a “nominee (director) of the founders” and not independent.

Read: DN Prahlad’s appointment to Infosys board makes some shareholders uneasy

Happenings in several Indian companies over the years have also shown that the behaviour of even some of those that meet the criteria is not always independent. In some cases, entrepreneurs and promoters nominate former bureaucrats who have done them favours in the past as independent directors (Over the past decade, I’ve had two such try to intercede with me on behalf of a now disgraced financial markets entrepreneur who believed he always got bad press from Mint). This is not to besmirch the reputation of all former bureaucrats who are independent directors. In other cases, they nominate friends (or relatives of friends) who rarely disagree with them. But the issue runs deeper. Even independent directors who don’t fall under either of the categories mentioned above are loath to go against the shareholders or promoters who appointed them in the first place. Some actually feel beholden to them for the substantial remuneration they receive in the form of sitting fees and commission on profits.

A 2005 law on independent directors (one third of the board of listed companies has to be made up of independent directors), a 2013 law on the term of independent directors (not more than two successive five-year terms) and a 2015 deadline on women directors (the boards of listed companies need to have at least one woman director, independent or otherwise) have sought to improve the governance of Indian companies and the quality of their boards. They have succeeded in part, but, ultimately, a board is only as good as the independent directors on it and how independent these independent directors choose to be. L’affaire Mistry provides another opportunity for everyone – regulators, promoters, independent directors, shareholder advisory firms, the media – to ask the old questions all over again.

R Sukumar is editor of Mint and tweets as @mint_ed

letters@hindustantimes.com