Excessive love of one’s state is less harmful than that of one’s country

The currents of regional patriotism run deep in India. We are a land of many languages, each with rich literary tradition. Naturally, people tend to identify most closely with those who wrote, and wrote well, in their own language. Ramachandra Guha writes.

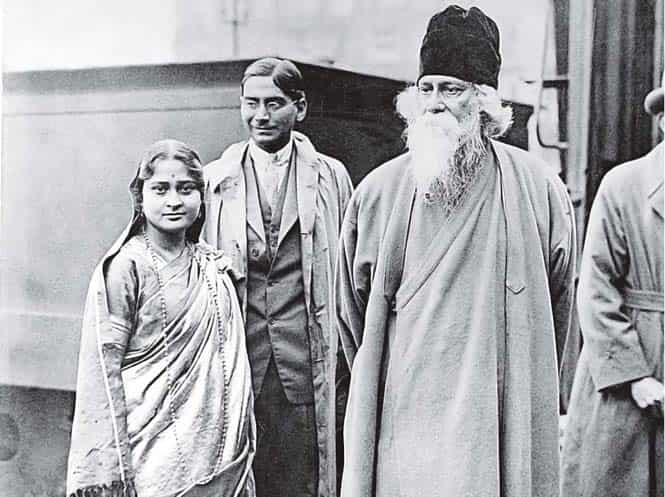

Some time ago, I wrote a piece in a Kolkata newspaper, arguing that the Kannada writer-actor-dancer-social reformer-environmentalist Shivarama Karanth was arguably as great an Indian as Rabindranath Tagore.

I had met Karanth, read his writings (admittedly in translation) and witnessed many examples of his substantial and continuing influence. From Girish Karnad to UR Anantha Murthy, from Girish Kaseravalli to Madhav Gadgil, novelists, film-makers, and scholars in Karnataka all told me that Karanth was the most remarkable person they had known.

Tagore too was a colossal figure. However, he had the advantage of great wealth and high social status, which gave him the freedom to do what he did, and to travel around the world to broaden his mind. On the other hand, Karanth was born in a family of modest means, and was totally self-made. He learnt through his own reading and his extensive travels on foot across the land. His novels and his revival of the Yakshagana dance-drama apart, he was admired in Karnataka (and by me) for his fearlessness, his leadership of many popular movements, his courageous work for the uplift of women, and his opposition to the Emergency. In purely aesthetic terms Karanth may not have been as gifted a writer as Tagore. But his moral courage equalled Tagore’s, while his physical courage exceeded that of the Bengali genius.

My claim that Karanth was in the Tagore league was mostly sincere. But it was also partly a provocation. In placing a mere Kannadiga on the same plane as their revered Gurudev, I expected to anger some Bengalis. They did not disappoint me. Thus a Bengali expatriate wrote that when he read my piece, “I almost choked on my breakfast cereal here in New York City, enveloped in a frigid Arctic morning with the thermometer registering a bone-chilling minus 22 degree Celsius.”

“I understand you’re now ‘middle-aged’,” my correspondent continued, “but that’s too early to have an addled brain. But then, like the Sahibs of yore, could the heat of India melt your gray cells too soon? Could it be the brain is fried prematurely by the merciless Indian sun?”

The provincial pride on offer in Bengal has a solid basis. From the 19th century, the province has produced a steady stream of great writers, social reformers and creative artists. However, in projecting their own, the Bengalis have had one inestimate advantage — namely, that their intellectual class commands a great felicity with the English language. This has allowed their province’s achievements to be broadcast more widely than equally substantial contributions from other parts of India.

Because of Bengal’s pre-eminence in the field of history-writing, we have been taught to think that the province was the “crucible of modernity” in India. In truth, the agenda of gender-and-caste equality, and modern rationalist thinking, was carried forward far more fully in western and southern India. Phule, Gokhale, Ambedkar, Narayana Guru, and EV Ramaswami have had a more enduring influence on the course of Indian life than their counterparts in Bengal. “Modernity” may have been born in Bengal; but it was nurtured and activated in Maharashtra, Tamil Nadu, and Kerala.

Remarkable writers and activists have been produced in all states of the Union. About a year before I placed Karanth on the same plane as Tagore, I got a mail from a Tamil resident in Puné. “As a historian, you have surely heard of [Subramania] Bharati,” he wrote, “but know little about him.” Then he continued: “A great poet, writer, linguist, revolutionary freedom fighter, philosopher, and non-conformist Tamil Brahman all rolled into one. His writings and poems touched all subjects — at least I have not come across anyone who can even be compared to him. And he lived only 39 years. I dare say, Tagore is a distant second. Don’t mistake my suggestion to be a provocation, it is [the] plain truth.”

The currents of regional patriotism run deep in India. We are a land of many languages, each with a long and very rich literary tradition. Naturally, people tend to identify most closely with those who wrote, and wrote well, in their own language. What Karanth is to the Kannadigas and Bharati to the Tamils, Vallathol perhaps is to the Malayalis and Fakir Mohan Senapati to the Odias.

However, the sense of local pride goes well beyond language and literature. Each state of the Union takes pride in the freedom fighters it has produced, the historical temples, mosques, churches, and gurdwaras it is home to, the forms of music, dance, dress and cuisine unique to it.

And in its cricketers too. A journalist from Mumbai recently visited south Bangalore to cover a closely-fought election contest. He found the residents torn between the BJP candidate and the Congress candidate, yet united on one thing: that GR Viswanath was a better batsman than Sunil Gavaskar.

To be sure, there is an inescapably rivalrous element to provincial pride. The Bengali in New York was enraged that I had equated a mere Kannadiga with his icon. The delight of the Odias in their tongue being declared a ‘classical language’ is enhanced by the fact that Bangla has not been granted that honour.

On the whole, however, provincial patriotism is salutary. It facilitates a deeper engagement with one’s state, and its finest forms of cultural expression. I myself think that an excessive love of one’s state is less destructive than an obsessive love of one’s country.

Ramachandra Guha’s most recent book is Gandhi Before India You can follow him at @Ram_Guha

The views expressed by the author are personal