‘The Cellular Jail should be a place of pilgrimage’

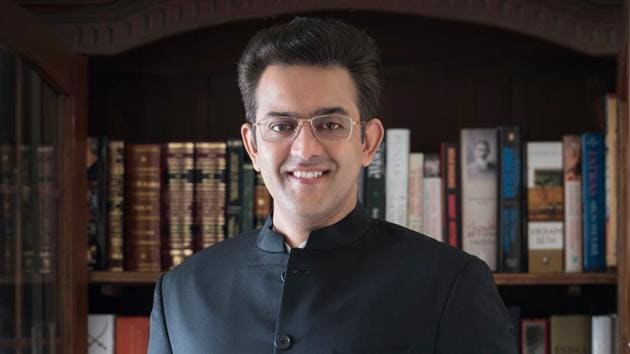

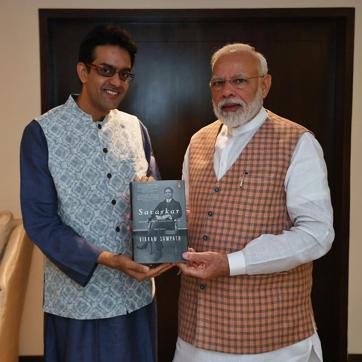

Says author Vikram Sampath, whose new book charts Vinayak Damodar Savarkar’s journey from a small village in Maharashtra to the heart of the Indian independence movement

navneet.vyasan@htlive.com

When historian Vikram Sampath sat down to pen an ambitious biography on Vinayak Damodar Savarkar, Aristotle’s quote reverberated in his mind — ‘The artistic representation of history is a more scientific and serious pursuit than the exact writing of history. For the art of letters goes to the heart of things, whereas the factual report merely collocates details.’

A challenge Sampath readily accepted was to make the read engaging. He acknowledges the obvious fact that, the history of India, more often than not, “has been written in such a dry, insipid manner that they have not caught the attention or fancy of readers, especially the youth”.

Sampath is among the new wave of acclaimed historians. The likes of Manu Pillai and Ira Mukhoty’s writing prowess have drawn the younger lot of Indian bibliophiles into picking up extensively researched non-fiction.

In 2004, after a political tussle broke out with the removal of Savarkar’s bust in Port Blair, Andaman, the never-ending polarising opinions on the freedom fighter piqued Sampath’s interest in him. “The incident of the dislocation of the memorial plaque in Savarkar’s memory at the Cellular Jail was only a trigger that got me interested in the man. Ever since, the regularity with which his name gets invoked in contemporary political discourse by both his proponents and opponents further fascinated me,” he says.

“Here was someone who had left this world way back in 1966, yet so much of modern discussion, among politicians, media and society at large happens around him. As a curious and an objective historian, when I surveyed the material that existed on this person who polarizes public opinion in India today like few characters of the past do, I noticed that there were hardly any biographies of his written in recent times in a dispassionate manner. Hence I took it upon myself to write his biography,” he adds.

Sampath says there is another volume in the works that will trace his life from 1924 to 1966. “Given the vast amount of research material that I had gathered, I decided to divide it into 2 volumes- the first one, that has just come out, covers his life from his birth in 1883 to his conditional release from prison in 1924. The next volume will cover the story from 1924 to 1966,” he says.

His latest release, Savarkar: Echoes of a Forgotten Past, is testimony to the rise in standards of ‘researching with the eye of a historian and writing with the flair of a novelist,’ as historian William Dalrymple puts it.

Humanising Savarkar

It never occurred to Sampath that Savarkar will, in fact, show him the way when it came to humanising the independence activist. “I just had to follow his advice from his memoirs where he was very open about sharing details of his life. He wrote, ‘While it is nice to describe a beautiful rose in full bloom, it would be incomplete without a description of everything — right from its roots, the stem, the manure and nutrients that have sustained it, the fresh and dried leaves as also the thorns, in order to conceptualise the beauty of that rose in all its dimensions. Likewise, for a human being’s biography, he needs to be presented “as-is” and not “as-should-be” — from head to toe, nothing more, nothing less, as transparent and true to reality as one can be’,” says the author.

It is safe to say that, today, Savarkar, enjoys a God-like status among those who revere him. So, humanising Savarkar might spell trouble for him. Was that something he was worried about? “Honestly, the hyper-sensitivity or the name-calling does not bother me one bit,” he says, as long as he has done complete justice to the character to the “best of his ability,” his conscience is clear.

A misunderstood rationalist?

The debate on Savarkar’s religious and spiritual beliefs has been never ending. “Savarkar was a pragmatic, rational thinker who was anti-ritual and stood against all antiquated practices that held us back as a country or as a community. In his 1923 treatise titled Essentials of Hindutva, that he penned from the confines of the Ratnagiri prison, he makes it clear that Hindutva had nothing to do with the theological constructs of the Hindu religion or its practices. The latter, he says, was a subset of the larger rubric of a cultural identity and nationalistic marker,” he says.

Unfortunately, Sampath says, Savarkar’s ideals and thoughts are considered bigoted today by many. “His book called for unity of all people who consider this land sacred and that of their forefathers. To that extent, far from being divisive or bigoted, it was all-inclusive and embracing. Savarkar conceptualized it in the specific context of the dangerous Khilafat Movement that Gandhiji had embarked on that led to large-scale communal polarization and subsequent riots. Someone needed to articulate an intellectual counter and response to this and that was exactly what Savarkar attempted to do,” he says.

Savarkar has not been given his due credit

The author says, researching on the revolutionary’s life changed him, in the sense, it made him realize that we as a nation have forgotten his contributions. “The research made me realise how little we know about our own history, especially that of the Indian freedom struggle. We have been indoctrinated with a certain narrative of what won us our independence for way too long. Alternative stories and versions have seldom been given the importance they deserve, only because of political considerations. The research opened the eyes of someone like me who has also been a product of this same sanitised education system to the fact that the armed struggle for our freedom (right from the 1857 War to the 1946 Naval Mutiny of Bombay ) and the innumerable heroes and heroines, including Savarkar, who made immense sacrifices and contributions to our nation, have been blissfully forgotten by us,” he says.

“We are an ungrateful country and forgetting our bravehearts is doubly insulting their legacy, in addition to erasing them out of our collective consciousness. The Cellular Jail should be a place of pilgrimage for all our young students in schools and colleges so that they are sensitized to the realities of how our ancestors suffered to get us the free air that we breathe today as Indians. However, we don’t even have or even if we do, a casual reference, to the jail or its inmates, the torture they faced etc,” adds the writer who won Sahitya Akademi’s first Yuva Puraskar in English literature for his work on Gauhar Jaan.

Kala Pani

The picturesque shimmering beaches of Andaman Islands that now attract thousands of tourists, was once a place where the Indian independence movement’s heroes were subject to barbaric brutality.

Kala Pani or Kala Pani ki saza was a term used for the incarceration of criminals who were deemed to be extremely dangerous by the British. Those who faced this punishment were generally revolutionaries, political dissidents and hardened criminals. The overseas journey also threatened these prisoners with the loss of caste, which also led to their social exclusion.

Savarkar, after being arrested in then Bombay, was moved to the Cellular Jail, where he was reunited with his brother Ganesh. “The Cellular Jail should be a place of pilgrimage for all our young students in schools and colleges so that they are sensitised to the realities of how our ancestors suffered to get us the free air that we breathe today as Indians. However, we don’t even have a source to learn and understand what happened to the prisoners and the torture they faced etc,” says Sampath.

Mistaken identities

The author refuses to subscribe to all the right-wing and left-wing labels that people spout so generously today. “Bhagat Singh has been appropriated by the left-wing, though in reality, he was an admirer of Savarkar. He even got the second edition of Savarkar’s book, The Indian War of Independence 1857, published,” he says, adding, “Similarly, communists such as SA Dange and MN Roy held Savarkar in high esteem and always called him as their “comrade”. Ambedkar and Savarkar too shared fondness for each other, given that their views on a complete eradication of the caste system had lots in common.”

Sampath mentions how in 1966, after Savarkar’s death, the then Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi paid tribute to him. Gandhi had said, “It removes from our midst a great figure of contemporary India. His name was a byword for being daring and patriotism. Mr Savarkar was cast in the mould of a classical revolutionary and countless people drew inspiration from him.”

Tilak’s influence

Savarkar idolised Tilak from a very young age. In fact, the author says, under Tilak’s tutelage Savarkar organised the first-ever bonfire of foreign clothes in India in 1905 as a student of Pune’s Fergusson College.

“But even Tilak might be designated as “right-wing” today given he started the Ganeshotsav in Maharashtra and invoked nationalism through the persona of Chhatrapati Shivaji. Our discourse has become so skewed and shrill with absolutely little place for nuance and instant labels and putting people into boxes,” Sampath signs off.

navneet.vyasan@htlive.com