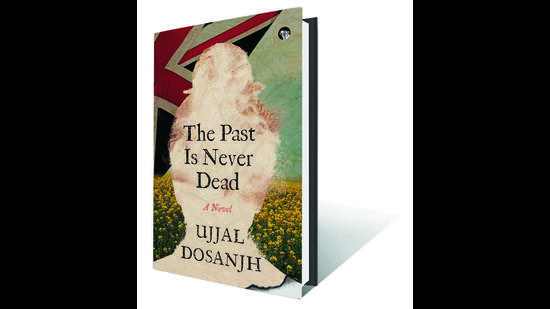

Review: The Past is Never Dead by Ujjal Dosanjh

A debut novel that packs in a good overview of Punjab’s caste history as it is transposed into the settlements of second and third generation Punjabis in the UK

About a decade ago, in the UK, I was confronted by fellow Indian students who did not appreciate my online advocacy for Dalit rights. Once, six of them, each from a different state of India and belonging to different castes – one a Brahmin, one a Sindhi, another a Gujarati Bania and so on – invited me to a mutual friend’s home, and then proceeded to bully me. I was shocked by their intense hostility. Thus far, they had been friends with whom I had dined, shopped, socialized, and shared conversations about longing to return to India. One, a Sikh, had been a close friend for a long time. I believed then that all Punjabis are open to other people and cultures. This was fated to be proved wrong, as she took offence to my anti-caste position in the classroom. Perhaps, it had nothing to do with her religion. Still, she grew excessively irritated with a Dalit man.

William Faulkner’s Requiem for a Nun has a sentence that reads: “The past is never dead. It’s not even past”. Ever since the novel’s publication, that sentence has been referenced numerous times in US Presidential speeches and Hollywood films, and even provided the title of a 2023 Faulker biopic. Lawyer, and occasional politician Ujjal Dosanjh’s debut novel, The Past is Never Dead, set in Punjab and the UK, and takes caste as its central theme, also draws from Faulkner’s phrase.

The protagonist, Kalu, who left Punjab at a young age, realises the hard way that he hasn’t escaped the old familiar social pressures completely even though he now lives in Bedford, UK. He wants to rent a large hoarding near Great Ouse Bridge and paint “Caste is never dead”. The Past is Never Dead, whose title rhymes with the words on Kalu’s banner, can be read as a dogged investigation, a work of communal self-reflection, and a bold statement on the status of the Indian diaspora. What made the protagonist reach such a conclusion? His wife, a Jatt, is murdered by her father for daring to marry the love of her life, a fellow Punjabi professor. A father killing his own daughter for marrying a Dalit is not uncommon in India but is unheard of in the western world except in the case of the murderous arson in Chicago in January 2008. In the novel, the father is shamed by his circle of “macho Jatt caste” friends who “taunted him as weak for not killing Simran immediately upon learning of her intention to marry Kalha”. The social pressure to maintain caste purity robs the father of humanity and he schemes to eliminate his daughter altogether.

The plot begins in Banjhan village in Punjab. Udho, who is a Chamar farmer, migrates to the UK and then brings over his wife, Banti, and son, Kalu. The child’s name is actually Kalha but villagers call him “Kalu Chamar”. Incidentally, “Kalu”, a derogatory reference to darker skin colour, is often used to address Dalits. After a death-defying escape from Punjab, Kalu reaches the UK, where he grows up. His first girlfriend is Christine, a white woman whom his conservative Punjabi mother dislikes. But Christine loves Kalu and has his back when he is mocked and disparagingly called a “rag-head cunt” for wearing a turban. Eventually, though, Kalu finds Simran, a doctor whose father is also one.The couple strive to have a beautiful family and raise their son, Angad, together in a world filled with love, laughter, and excitement. However, all this is crushed violently.

Largely set in Bedford, site of early anti-caste activism in the UK, the novel strikes you right from the get-go. It is also possibly the first book to be published out of Canada that has a Chamar protagonist, and exposes how the caste system is alive and well within the subcontinent’s diaspora. A Jatt himself, Dosanjh’s realisation that the template of caste is strongly ingrained, gives his novel heft.

The isolation marked by Dalits abroad is atemporal and has a deep psychological dimension. The Dalit body is twin-marked. Take what happens when Kalu and Simran are at a bar. A Jatt gang shows up and assaults Kalu. Anguished, he wants to get back at them but realises, “I can’t wish away my caste and colour”. Udho, who is intimately involved in the social life of Ravidasias, tells Kalu: “The Jatts hate us. The whites look down upon us”.

The Past is Never Dead packs in a good overview of Punjab’s caste history and social life as it is transposed into the new settlements of second and third generation Punjabis in the UK, who often swear by the words of the great saints and Sufis in gurudwaras. In a scene outside the courthouse, the author presents three groups: the first are supporters of caste, the others are opponents, and the third is a group that’s somewhere in between. These distinctions help the uninitiated to understand the complexity of caste in the diaspora. The dualisms generated by supporters and opponents of a cause actually result in victims being held hostage for longer. In the expanse of liberation, victims are presented as samples to be distributed. However, those who see this happening choose only to observe rather than do anything proactively. Such in-between groups, who are interpreted as being rational, often become defenders of tradition.

Despite his devout Sikh self, Kalu is still looked down upon as a Chamar and is punished for attempting to humanize those around him. He is kidnapped and his head is forcibly shaven, taking away memories even of the indignity he suffered at the hands of native English racists. Ravidass and Ambedkar feature whenever an anxious Kalu races through the phalanx of trauma and rebellion.

Diaspora and caste: An old story

The modern diasporic community of India is nearly 180 years old. Its recorded movement took place during colonial rule in India. Many Indian farm labourers were recruited to work in sugarcane fields as far afield as the Carribean and Fiji. Many Shudras and Ati-Shudras too were hired in large numbers. Towards the end of colonial rule, many of those who served the Union Jack during the First and Second World Wars and those whose labour was indispensable to the rebuilding and development projects of Great Britain were taken along as British nationals. When Indians left to settle in their new country, they carried with them certain attributes that made them confident about the greatness of their culture. Their religious faiths and social practices were held close as they warded off the racism they faced in new lands like UK, Canada and Australia. As they settled there, their common heritage led to the forming of deep bonds. But old fissures too began to reappear. While caste became a defiant marker to be asserted by one set, it also became the identity that another hoped to shun. The latter did this by excelling in various avenues.

Desis and caste

Stories of the diaspora often depict the uniqueness of the desi character. Readers learn about the karma of brown folk in the US or about those who follow the activist path of anti-colonial, anti-colourist politics. There are no stories about Dalits and the politics of caste.

The Past is Not Dead focuses on the menace of caste, telling us how caste practices are maintained. However, the Dalit protagonist here is not meek and docile. Instead, he is an assertive and lovable family man, who is simply living his life and, in that journey, comes across as people who do not look at him with impartial appreciation. Yet, he does not give up on his abilities. He is willing to wrestle with the system for his rights. He is non-confrontational but upright when it comes to the rights of citizens. Kalu is a leader, who is an ethical partner in the making of a new politics. He contests for the Labour party and is elected to Parliament. A personable individual, he wants to do good and in doing so, hopes to inspire mass change in the morals and behaviour of society. Though tragedy and violence adds gravel to his path, he manages to stay compassionate. He is committed to the well-being of all and even provides generous opportunities for those who slaughtered his beloved wife. The plot in the second half revolves around getting justice for Kalu, who is attempting to balance his responsibilities as a single father, a son to ailing parents, and as a professional, even as he fights for justice for his murdered wife and runs political campaigns. Meanwhile, the antagonists are gaining limited power within their social circles. For the Jatts, the gurudwaras become places where they can demonstrate their influence. When Udho goes to a gurdwara, he is assaulted by those who are averse to a Chamar sharing their place of worship. Incidentally, every gurudwara I’ve visited outside India is dominated by aspirant upper castes. A parallel can be seen in the Telugu state organisations in the US, which are easily identifiable with the Reddys and Kammas.

I often testify as an expert in court cases in Canada and the US where the victim has faced abuse and violence based on caste. The Canadian immigration agency is keen to follow a template on caste-based persecution in asylum and refugee policies. The Western world is now embracing the anti-caste work of Dalits. Legislation is being discussed, and many institutions have outlawed caste from their campuses. Dalit organisations worldwide have taken it upon themselves to defend the human rights of those oppressed by caste. Caste has now become an intimate experience of second and third generation Dalits in the diaspora. School children are often questioned about their caste, food choices, and even ancestry by classmates who should have been removed from this particular reality. In the book, Kalu’s son, Angad, is reminded of his caste by a Jatt boy. When he hears of it, Kalu realises “the trek to Delhi and flight to London had all been an illusion”. Refusing to give in to bullies, he advocates for anti-caste training. Growing up under the gaze of Udho, Banti and Kalu, Angad is prepared to dare the casteist gaze. When caste is understood rather than hidden – as Udho tried to do throughout his life – all the pieces fall into place, and every experience from marriage, love, school, family, community, and politics starts to make sense for a Dalit. When caste pride becomes the politics of outcastes, a new identity foregrounds their existence. This is seen when Kalu prefers to be identified as “Dr Kalu Chamar”, MP of Bedford.

Dosanjh is a writer with an ethnographic insight whose characters live on with the reader. That he is a former premier of British Columbia in Canada gives one hope that an anti-caste agenda will make it to the core of that country’s politics. In the UK, where this novel is largely set, Ambedkarite-Buddhist politics has been around for over 50 years and is a testament to the power and efficacy of Dalit organising. It is now time for Dalits to participate in state affairs to the fullest wherever they are in the world.

Suraj Yengde is a WEB Du Bois Fellow at Harvard University. His forthcoming book, Caste: A New History of the World, is a study of castes outside India.