Review: Business of Taste by Centre for Science and Environment

Business of Taste highlights high-nutrition foods that have fallen out of traditional diets at calamitous cost

There’s no greater indictment of the 21st century Indian state than the persistence of mass malnutrition. On September 18, The Lancet published the latest shocking statistics: in 2017, malnutrition was the predominant risk factor for death in children younger than five years in every state, accounting for 68•2% of total under-five deaths, and the leading risk factor for health loss for all ages. Prevalence of low birth-weight was 21.4% and child stunting was an extraordinary 39.3%. Even more unconscionably, anaemia (generally easily combated by healthy, varied diet) in children under five years of age was 59.7%, and 54.4% of all Indian women of reproductive age were also anemic.

The Lancet noted progress has been made over recent decades, but “even with these improvements, India continues to have a high prevalence of undernutrition, combined with an increasing prevalence of overweight and obesity in a subset of the population. Addressing this persistent development problem requires India to ensure implementation of practical and effective policies and interventions across the life cycle that consider the subnational variations and the context of each state.” To put it considerably more crudely, “it’s the culture, stupid!” India’s unendingly diverse demographic landscape has proven impervious to sweeping solutions, and the only things that have worked are targeted micro-strategies addressing specific communities and circumstances.

Here, it’s useful to recall Amartya Sen’s insightful analysis of the Bengal Famine of 1943, when up to three million people died in what he characterized as a man-made catastrophe, writing “famines are easy to prevent if there is a serious effort to do so, and a democratic government, facing elections and criticisms from opposition parties and independent newspapers, cannot help but make such an effort. Not surprisingly, while India continued to have famines under British rule right up to independence… they disappeared suddenly with the establishment of a multiparty democracy and a free press.” That conclusion rings conspicuously hollow in 2019, as each aspect of the democratic system named by Sen is under threat. The result is famine, albeit unrecognized and undeclared, as hundreds of millions of Indians struggle for survival, amidst unnecessary illness and premature death on an extraordinary scale.

If it is culture that underlies this abysmal pan-Indian performance (a handful of states, mainly in the south and north east, are much better off than the others), the main maladies can be divided into two broad groupings. The first – loosely, patriarchal systems - is best illustrated by findings from the Rajasthan Nutrition Project (designed by Grameen Foundation and Freedom from Hunger India Trust) where the simple act of rural families, including women and children, eating their meals together with the men immediately decreased malnutrition. The study findings are extremely stark: the greater women’s decision-making authority in a household, the greater their food security. 39 percent of women classified as having a high degree of autonomy were food secure, versus only 12 percent of women with low autonomy. In every way, statistics for nutrition closely shadow those representing women’s welfare in every part of the country.

The other category of cultural failings underlying India’s terrible performance in combating malnutrition is addressed directly by Centre for Science and Environment’s excellent First Food series of books. The most recent volume, Business of Taste, features 24 contributors, with editorial direction from Sunita Narain, and concept and research by Vibha Varshney, throughout highlights high-nutrition foods that have fallen out of traditional diets at calamitous cost. In the chapter about Alternanthera Sessilis (Anagone Soppu in Kannada) Puttama, a 75-year-old elder of the Soliga people indigenous to the Western Ghats recalls, “when we were young, we consumed at least 50 varieties of greens, over 40 varieties of wild fruits and over 30 vegetables and crops that grew in the forest and in our farmland.” That bounty has withered drastically. Now she says they consume mainly “rice and rice-based foods, black tea, and packaged snacks.”

Narain (the director-general of CSE) summarized the problem neatly in her introduction to the previous First Food book Culture of Taste, writing “We don’t have to first eat badly and then rediscover healthy and medicinal food that is not filled with toxins. We have a living tradition of healthy food still eaten in our homes…But knowledge of this diversity is disappearing. It is getting lost because we are losing the holders of that knowledge [and] it is also getting lost because we do not value their knowledge. Our food is getting “multinationalised”, industrialised, and “chemicalised”. It is the same anywhere and everywhere. Strangely, this McDonaldisation of food has been peddled as a sign of modernity and prosperity. It has become aspirational.”

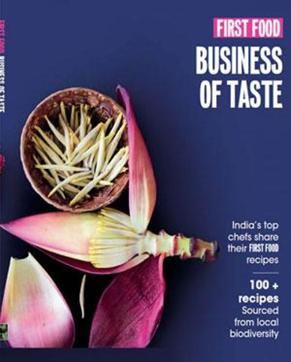

It is that last aspect of prevailing food culture that the First Food books have especially effectively combated, with their nuanced storytelling, unexpectedly lovely visuals, and impressive range of correspondents with boundless enthusiasm for the subject. Business of Taste takes it one step further by including contributions from 10 of India’s best-known chefs (though, regrettably, including only one woman). Thus we have The Bombay Canteen’s Thomas Zacharias on moras bhaji, “a halophyte that grows in salty lands or brackish waters” and Indian Accent’s Manish Mehrotra’s recipe for fish cooked with gongura (aka roselle) “a unique ingredient which gives acidic and pickle flavours to a dish.”

Each of these delightful books has been an individualistic grab-bag of different topics, with a consistent emphasis on cultural, culinary and environmental history. A Taste of India’s Biodiversity (2013) packaged recipes in categories like Breakfast, Beverages and Sweets along with in-depth articles on ingredients like mahua, and author-driven essays such as Aparna Pallavi’s quirky personal history, “Marathi food for [a] Bong palate.” Culture of Taste (2017), in my view the singularly outstanding volume in the series, had sections on leaves, flowers, and seeds, as well as preservation and business. Culture of Taste takes a similarly expansive view, spanning intriguing recipes (Uttarakhand’s flavoured salts! Manipuri bamboo shoot pickle!) as well as essays on diverse food traditions, and the means of livelihood for farmers and foragers.

Read more: India can lead the way in nutritious, sustainable diet, say experts

We live in paradoxical times, where my local supermarket in Goa stocks quinoa from South America on its shelves, but not its locally-grown relative, tambdi bhaji (red amaranth), which is equivalently power packed with vitamins and iron. This is where the CSE books represent an invaluable resource, for professionals as well as amateur cooks and consumers with their meticulous listing of dozens of greens, vegetables, seeds and fruits that literally grow in our backyards, and – should the necessary cultural shifts occur - can quickly supply the vast majority of the nutritional needs of the entire subcontinent.

There are many fascinating examples, but perhaps for obvious reasons, I was especially drawn to the chapter on Eclipta Prostrata (a close relative of the sunflower) written by Meenakshi Sushma, which describes nothing less than a miracle plant, used by various indigenous peoples as a cure for malaria, migraine, body ache, and “is full of adaptogenic properties – it increases the body’s tolerance to mental and physical stress. It is rich in vitamins, minerals and micro-nutrients like sodium, magnesium, copper, iron, calcium, zinc, and potassium.” What’s more, a paper in the International Journal of Moleculate Medicine reported the plant “stimulated the hair follicles” and could provide a cure to baldness!

Vivek Menezes is a photographer, writer and co-founder of the Goa Arts and Literature Festival