Nandana Sen: When I was growing up, my mother was the superstar in our family

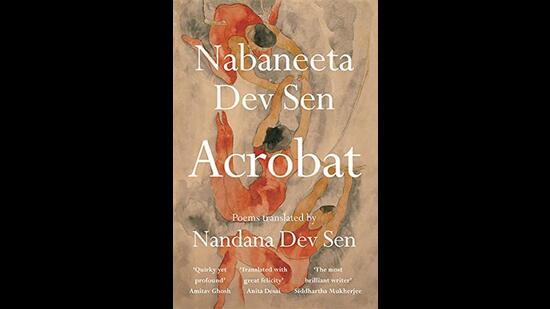

Author, child rights activist and actor Nandana Sen speaks to us about translating her mother Nabaneeta Dev Sen’s poems from Bengali into English

Your mother was a formidable literary figure. What gave you the courage to translate her?

We had been translating together for decades before Acrobat came into the picture. We started when I was in college. I must admit that I didn’t see myself as a translator back then. I was basically helping Ma have a body of work available in the English language that she could share.

Later, for her 75th birthday, I had a book published for her as a surprise gift. It was called Make Up Your Mind: 25 Poems About Choice, and was brought out by iUniverse as a bilingual edition with Ma’s poems in Bangla and my English translations alongside. Most of the poems that I had chosen for that book were taken from Ma’s latest poetry collection Tumi Monostheer Koro.

She adored those translations. That made me happy because she was very ill in her last year and I knew that she had unfulfilled dreams that were important to her, such as publishing her work for an international audience. It was unbelievable that it hadn’t happened despite the fact that she had over a hundred books in print. She was not only a formidable literary figure but also a very distinguished academic. There was a sadness in her about the fact that her books weren’t accessible to a global audience but she also recognised that it was her choice to have always written in Bangla even though she could write just as beautifully in English.

Ma passed away exactly a year from the date of diagnosis of her pancreatic cancer. Before that, something truly amazing happened. A copy of Make Up Your Mind: 25 Poems About Choice fell into the hands of Jill Schoolman, the wonderful founder publisher of Archipelago Books – one of the leading global publishers of literary translations. She loved the book, and suggested that we do one together. She had a clear idea – my translations of my mother’s poetry. Ma was delighted. We signed the contract for this book two weeks before she passed away. Ma wrote about it in her very last column. There was a particular kind of promise that I felt I had made to Ma.

Nabaneeta di used to hate the fact that her poetry, and women’s poetry in general, is often assumed to be autobiographical. How did you grapple with that aspect of her work?

Actually, this is true for women poets, women artists, all women who are in the public eye. It’s quite rightly said that men do not go through the same experience of being constantly judged and, in some ways, imprisoned. She did not like the fact that her entering the public arena made her fair game for this kind of extreme scrutiny. It was frustrating and, because of this, she stopped publishing her poetry for a while even when she was writing a lot. When a woman writes, the readers assume that she’s writing about her life. Ma felt that this easy identification between the writer’s imagined world and literal world does not happen in the case of male writers.

It is true that a lot of her poetry came out of her most intimate emotions but she felt burdened by the fact that it made readers assume she was writing about exactly what was happening in her life. What followed from this was their wanting to know more about her life. It was as if she had given them permission to be curious. It was a real tussle internally. She wanted to be relentlessly honest about herself in her poetry but that poetry was also giving her away to a point where she didn’t feel comfortable with the voyeurism that came in response to her emotional nakedness.

As a translator, I could not worry about the conclusions that readers would jump to. My accountability as a translator required me to focus on ensuring that I was being true to the emotions, images, and linguistic choices made by the poet. I had to recreate all of that from Bangla into English in a way that was universal and would make sense to readers who may not be familiar with all of the cultural, historical and political context that Ma wrote her poetry in.

For me, it was more of a priority to make sure that the universality of the poems would be conveyed. I did not bother much about extra-literary considerations that I have no control over.

You have talked about the challenging parts of translation. Tell us about the fun you had.

I have inherited my mother’s love for rhymes, and she inherited it from both her parents – Narendra Dev and Radharani Devi – who were poets. Ma loved poetry in every form, including poems with complicated rhyming and metrical structures. If you look closely at the poems in Acrobat, the rhymes are sometimes internal. They are not obvious because they are not necessarily placed at the end of a sentence. It is a lot of fun to stumble upon them because they are like inside jokes. You can discover them only when you read a poem over and over again.

There are several poems like that. One of them is called Sometimes, Love. It does not read like a rhyming poem but it’s actually full of internal rhyme. Another one that has a complicated metrical and rhyming structure is called Right Now: Forever. It is one of her most iconic poems. Ma loved reading it out at every kobi sammelan (assembly of poets) that she went to. I spent months on that one poem. I wanted it to be perfect. I was loyal to the rhythmic structure and also to the way the poem inhabits the page. I believe that the way a poem takes up space also contributes a lot to the emotion it creates. The stakes were high but I had fun. I love Ma’s poems.

What is striking about her poetry is that, on the one hand, there is this very conversational style where she addresses the reader. At the same time, there are words that are quite classical and archaic even, and the metaphors are drawn from our epics and scriptures. Ma could take the stories of our classical heroines and turn them into every woman’s story and ultimately into her own story. She also liked making up words. She was fantastic at conjuring them like magic.

Working with all these layers was hard but also enriching for me. I had choices to make, and that’s when my own creative, imaginative and political sensibilities entered and had fun.

Name some poets that Nabaneeta di introduced you to, poets you continue to read.

Oh, so many! First and foremost, I’d say Rabindranath Tagore. Well, as a Bengali, I grew up with his poetry and his songs all around me. There was so much of him in our house. People on the maternal side and paternal side of my family were close to Tagore. They knew him personally. His influence has been deep and abiding. Ma also introduced me to the poetry of Maya Angelou, Pablo Neruda, Mary Oliver, Margaret Atwood, Alice Walker, Anna Akhmatova, and so many more. She loved translating poetry from across the world, especially poetry by women. She translated haikus by Japanese poets. She went to Israel and learnt Hebrew so that she could translate women poets from there. She also translated the 14th century Kashmiri mystic poet Lal Ded. Ma had a real commitment to translating poetry from across the world.

How did her passion for translation rub off on you?

Ma spoke a lot about the critical role that translation plays in sustaining the literature of the world. Living in a multilingual country like India, she felt very strongly that the younger urban generation was losing its connection to the mother tongue. She was also a huge admirer of Indian writing in English, and followed it closely before it exploded. She had anticipated back in the 1970s that Indian writing would be represented to the world through Indian writing in English rather than Indian writing in the regional languages, which we have such a long and rich tradition of. She was a professor at the Department of Comparative Literature at Jadavpur University in Kolkata. She saw translation as a way to understanding each other better, as a means to solidarity. She made me think about the importance of translation in cultural literacy.

In your introduction to the book, you mention that writing poetry was liberating and healing for her. Did the process of translating her poems evoke the same in you?

It was painful to work on Acrobat after Ma passed away. That was also when the pandemic hit us. It was a strange and disturbing time for everybody in the world. To be steeped in Ma’s words and her emotional history, many layers of which I had not fully understood while she was alive, was a kind of profound and moving experience for me. It wasn’t the easiest of book projects. I couldn’t work on anything other than my mother’s poetry. Every poem brought her voice back to me, and not in a metaphorical way. I could actually hear her voice. It was disorienting to feel her so close but also know that she was far away. It was heartbreaking process but it also allowed me to continue having a conversation with her. I felt like every poem was a message from her to me. Working on every word and every line and every rhyme gave me a chance to stay connected with Ma, which is another reason why translating took me much longer than I thought it would.

Aren’t the poems in this book from different periods of Nabaneeta di’s life?

Yes, these poems are from across 60 years of her life as a poet. She published her first book of poems when she was barely 21, and she kept writing poetry until the last weeks of her luminous life. Poetry was a survival tool for me, and it became a coping mechanism for me as well. It absolutely helped me in healing as I was grieving for her, although it was not obvious at the time. I was working on the book during the Covid-19 pandemic, when we were all so closed off. There weren’t too many ways of getting support. You couldn’t cry on your best friend’s shoulder, and you couldn’t go to your therapist. Translating Ma’s poetry was certainly my way of healing.

While growing up, did you take pride in your mother’s accomplishments, or were you jealous that you had to share your beloved Ma with so many admirers and students?

I was always incredibly proud of her. She used to laugh and say that one of my weaknesses was that I didn’t have the jealous gene. I was a good student but not a competitive one. I didn’t compare myself with others. I am sure this had a lot to do with the way Ma brought me up. Apart from her huge talent as a writer, she had the greatest capacity to love. I was as proud of that as I was of her writing. She had so many admirers not only because she was a great writer but also because she was so emotionally open and welcoming and she made herself available. She opened her heart to everybody, whether it was her readers, her students, or the young women writers and artists that she mentored. She would spend hours even though she was incredibly busy.

Ma would actually answer random fan mail from people that she didn’t know and would probably never meet. But it was important to her to have that. She felt accountable to her readers, and she responded to the love that she got from them by giving that back. It was a beautiful thing to see, actually. When I was growing up, my mother was the superstar in our family. When we walked out of the house, she would be mobbed by people who wanted autographs. This is before the time of mobile phones. When those came in, of course, people would want selfies. My father (Amartya Sen) was beloved in academic circles but it was only after he got the Nobel Prize in 1998 that he became a household name. My mom was a household name all my life.

What did your father think of Acrobat?

He really loved it. He has always felt that my mother’s talents were not fully understood internationally, and he regretted in some ways that she didn’t pursue the academic work she had done in the origins of epic poetry. It was pioneering, and she got a distinction at Harvard and all of that. But she got so busy as a creative writer and as a mother and as a professor that she had to make a choice between her academic work and her creative work. My father was delighted that her work was represented to a global audience, finally after all these years, through this book. Thanks to Chiki Sarkar at Juggernaut Books, the book is also available to readers in India.

What projects are you working on?

I wrote a children’s book called Mambi and the Forest Fire, which came out in 2016. I am working on the second book in that series. Apart from that, I am doing a book called Mother Tongues, which Ma and I had started working on a couple of years before she passed away. It is a book of narrative non-fiction about three generations of women in Bengal. I have been approached to work on some translation projects. I’m trying to make a decision about what I can fit in. I have also completed writing a screenplay about the intersection of cinema, politics and journalism. There’s a lot of interest in it, so I’m busy with that as well.

You were writing a screenplay based on RK Narayan’s fiction. Is this the same?

It’s not the same but I am thrilled that you’ve done your homework so well. I had worked on a film script, which was an adaptation of Narayan’s novel Waiting for the Mahatma. It did not get produced eventually but that was a really fun project to work on. He is one of my favourite authors, and I got to meet him. Our common friend, N Ram, took me to see him. Narayan was so memorable. The female protagonist in the book is a freedom fighter named Bharati, who is outspoken, passionate, and committed to the cause. I asked Narayan about the inspiration behind this character. I wanted to know if there was a particular woman he was thinking of while writing Bharati. We spent about two to three hours chatting in his little garden, and he said, “Yes, of course there was.” I got very excited and asked, “Who was it?” He looked me straight in the eye with a twinkle and said, “It was you.” And I just melted. Narayan was such a charming man!

Chintan Girish Modi is an independent writer, journalist and book reviewer.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website