Jal Sanjhi: the holy art of painting on water

For half a millennium, the Vaishnav family of Udaipur has been practising this unusual form.

Navigating the maze-like lanes near Jagdish Chowk, I stopped several times to ask locals for directions to the Jal Sanjhi Temple on Kalash Marg, a narrow street lined with some of Udaipur’s most historic havelis. The banana-yellow house belonging to Rajesh Vaishnav, a practitioner of the unusual jal sanjhi art form, shares its entrance with the 500-year-old Shri Govardhan Nath Ji temple. The traditional doorway features intricate etchings of peacock feathers, cows, and royal figures crowned with the inscription ‘Jai Shree Krishna’.

The temple is dedicated to Krishna, who is lovingly called “Govardhan” after the sacred hill in Braj, where he was born. The hill itself is also believed to be a natural manifestation of Krishna. In the small room that houses the temple, Vaishnav greets me with prasad before preparing to demonstrate his water-based artistry, a practice he believes was bestowed on his family by divine grace. In one corner of the space measuring about four square feet are natural pigments; weathered stencils, their edges worn by a hundred years of use, rest in another. Two flat aluminium vessels of water catch what little light filters in, their surfaces gleaming before the sacred idols on the wall.

Rajesh Vaishnav belongs to an artistic lineage that stretches back 19 generations. The art of his illustrious ancestors — Hathiram Dasji, Chaturput Dasji, Behrud Dasji, Manala Dasji, and Ratan Dasji — flourished under the patronage of Mewar’s Maharajas, who made regular pilgrimages to the temple. Today, Rajesh and his son Ankur represent the latest link in this unbroken 500-year chain of tradition.

Vaishnav begins by creating layers in the water using two fundamental colours: white and black. While working, he explains the form’s use of eco-friendly practices and natural materials. “In jal sanjhi, we’ve traditionally used colours derived from stones, minerals, and natural powders. While we now source these natural pigments from specialized companies, my ancestors produced them by hand,” he explains. Gesturing to the soapstone pigment, he describes its white, zinc-like properties.

“These elements combine to create our base layer. For the darker tones, I incorporate coal powder,” he says. As Vaishnav adds yellow and green to his jal sanjhi to depict trees and plants, he mentions that Radha would create these water paintings using flowers and colours to please Krishna during their moments alone. Sanjhi compositions are crafted using an array of materials — flowers, leaves, coloured rocks, pebbles, paper, and powder — each adding layers of meaning to the visual narrative.

“This is among the most versatile storytelling methods I’ve come across,” says Nalini Ramachandran, author, Lore of the Land: Storytelling Traditions of India (Penguin Random House India). “It can be created on walls and floors, and then there’s jal sanjhi too — an art form with two variations. One involves depicting scenes from Krishna’s life using coloured powder on the surface of water, while the other is created underwater — thus highlighting the form’s nuanced creative evolution.”

In a chapter set in Braj, Uttar Pradesh, believed to be the birthplace of Sanjhi, Ramachandran’s book presents the craft through a conversation between the protagonist, Mohini, and a young boy named Gopal, a member of a Sanjhi artisan family. As the story unfolds, Mohini tries to understand the form: “I’m slightly confused. Is sanjhi the design made using flowers and stones or is it the name given to the paper stencils?” Gopal explains: “See, the traditional images created with flowers and stones are called sanjhi. Today, paper stencils are used to make these Rangoli-like designs with coloured powder — on the floor, on the surface of water, even underwater! And they are also sanjhi. Understood?”

Ramachandran speculates that sanjhi’s presence in Udaipur may be linked to the nearby Nathdwara temple. “Krishna is worshipped as Shrinathji there, the child avatar who lifted the Govardhan hill. It’s possible that the sanjhis created at various sites along the Braj Parikrama pilgrimage route are connected to those showcased in Nathdwara,” she says. She also draws attention to the symbolic significance of water in jal sanjhi. “There’s a story about how Radha, mesmerised by Krishna’s reflection in a water body, adorned it with a floral border, finding it picture-perfect. Jal sanjhi is believed to have originated from this very moment,” she says. The presence of water, especially the Yamuna river, is deeply tied to Krishna’s lore. Jal Sanjhi can be seen as a reflection of the deity’s qualities with the stillness of the water, essential for creating the art, running parallel to the unwavering poise with which he held up Govardhan hill.

“In Braj, a traditional sanjhi is made with flowers and colours on the floor or in water, inside a shallow basin or plate. It evolved into a temple art around the seventeenth century. Only a few temples continue the tradition today, where the design is prepared throughout the day but revealed only at dusk, after the aarti has been performed,” says Ramachandran.

The appeal of sanjhi lies in the precision with which artisans cut intricate stencils, coupled with the painter’s expertise in layering them, ensuring that the background remains undisturbed. At the temple in Udaipur, Vaishnav carefully retrieves some of the oldest paper stencils from his personal collection, and explains that crafting them is a time-intensive process which sometimes takes about 15 days to perfect. His own collection includes remarkably old pieces like a 450-year-old deer (hiran), a 250-year-old Yashoda Ji (Lord Krishna’s mother), a mango tree, Bakkasura, the demon sent by Kansa to kill the child Krishna, Udaipur’s City Palace, and some 100 other pieces which are about 150 years old.

Vaishnav gently places the City Palace stencil, made from handcrafted paper, onto the water’s surface. He then hand-presses colours onto it — similar to creating a rangoli — to form intricate designs on the water. “According to Vedic traditions,” he says, “Jal sanjhi has a special connection to unmarried girls during Shradh paksh, when they couldn’t participate in auspicious activities. These girls began creating artistic designs using various materials — flowers, dry fruits, lentils, food, and even cow dung.” He explains that while ‘sanjhi’ refers to painting, ‘sanjh’ means ‘evening’. “This art is deeply connected to Sandhya Mata, the goddess,” he says. “Young women would create these designs while praying to Sandhya Devi, hoping to find a good husband. The goddess herself represents the divine feminine through this artistic expression,” he adds.

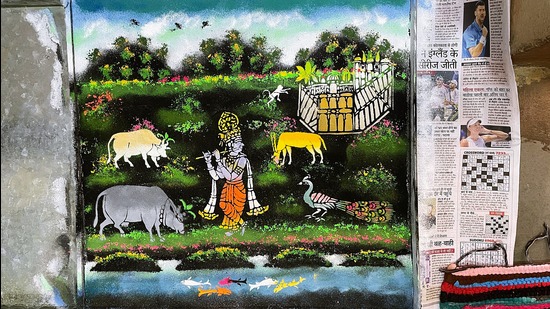

Within the space of an hour, Vaishnav has layered more than 12 colours and nine stencils on the water. He is methodical in his arrangement: first, the city palace; next, a deer, peacock, bull and cow, followed by a monkey, birds soaring through the sky, and fish swimming below. At the heart of the composition sits Lord Krishna. The entire jal sanjhi took nearly 90 minutes to complete. Once finished, the painting floated motionless on the water until Vaishnav reached into an adjoining vessel and stirred the surface, creating gentle ripples that animated it. He also reflected on the ritual of boiling the water beforehand, a practice that symbolizes devotional purity.

“The ripples that emerge when the work is completed makes the image float and this perhaps symbolises the flow of devotion in the hearts of Krishna’s devotees,” reflects Ramachandran. Both sanjhi and jal sanjhi embody the philosophy of impermanence, a reminder of the cyclical nature of life. “Only when a sanjhi or jal sanjhi is erased can a new one be created the next evening. I remember reading that jal sanjhis were immersed in the Yamuna after the evening aarti at a temple in Vrindavan every day. I’m not sure if this ritual still continues,” the author says.

Meanwhile, Vaishnav beams with pride as he completes his piece. He then leafs through an old book written in Gujarati and Mewari that showcase his art. It features stunning depictions of Makhan Chori, Shreenath ji, and Krishna Leela. Having created thousands of pieces through his life, he can now execute one in just two hours. These delicate water paintings typically last 24 hours, though covering them with glass can preserve them for up to 72. “Larger pieces might require about 10 hours to make,” he says. “During the five-day festival in Udaipur, we create these grand paintings for all the devotees. Beyond the festival, we’ve received prestigious invitations, including to the G20 summit — our greatest achievement yet,” he says.

Perhaps the devotional art is now set to move into the secular arena as well.

Veidehi Gite is an independent journalist.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website