World’s oldest known amputation from 31k years ago, and the myths it busts

In 2020, archaeologists excavated a skeleton from a burial site in Borneo and were struck by the fact that the lower left leg was missing, the wound having healed in a way that indicated a surgical amputation.

In 2020, archaeologists excavated a skeleton from a burial site in Borneo and were struck by the fact that the lower left leg was missing, the wound having healed in a way that indicated a surgical amputation.

Subsequent dating placed the skeleton at 31,000 years ago, making it the earliest known evidence of surgical amputation, and challenging the notion that hunter-gatherer societies of the time were inferior in their medicine skills to agricultural societies that flourished thousands of years later.

Before this, the earliest evidence of surgical amputation was from around 7,000 years ago. The remains of that individual, whose left arm had been amputated below the elbow, were unearthed near Paris, and reported in Nature Precedings in 2007.

The findings on the Borneo excavation were published in Nature this week. This individual had undergone the amputation during childhood, six to nine years before he or she died at age 19 or 20. The sex of the individual could not be determined.

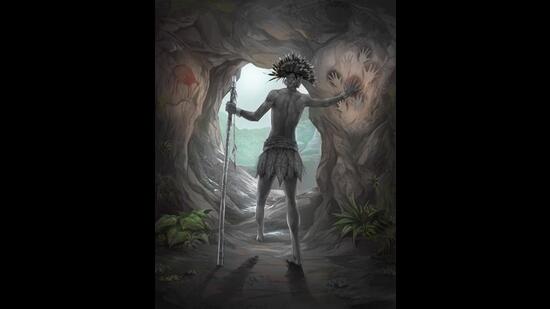

The site is in the Sangkulirang-Mankalihat region of Indonesia’s East Kalimantan province. It has some of the world’s oldest rock art, dated to 40,000 years ago, and it was to study this that Australian and Indonesian researchers began excavations in a limestone cave called Liang Tebo in February 2020.

“Here we discovered the skeletal remains of a young individual whose remains were intentionally buried with grave goods including ochre. The left foot was entirely missing, and the abnormally shortened tibia and fibula presented with evidence for healed bone,” Dr India Ella Dilkes-Hall, an archaeologist with the University of Western Australia, said in an email.

The age of the remains was estimated by radiocarbon dating of charcoal associated with the burial coupled with the dating of one of the individual’s teeth. The person had died between 31,201 and 30,714 years ago.

The fact that the individual survived such a serious childhood operation, followed by the healing of the wound, underlined not only the surgical skills of those who performed the amputation, but also a knowledge of medicine. Although no direct evidence survives of what exactly was used at the time of amputation, the researchers believe there is a strong case for the use of medicinal botanical resources sourced from the local rainforest environment.

“For example, Pangium edule is well documented as an important medicinal plant and traditional ecological knowledge recorded by the Iban of Sarawak documents the use of the sap from the inner bark as an antiseptic to treat wounds. I believe there is similarly a strong case for plant use in the way of plant-based technologies for bandages and wrappings,” Dilkes-Hall said.

“Evidence for a successful transtibial amputation performed ~31,000 years ago is incredible as it demonstrates the people’s performing this operation possessed incredible knowledge around human anatomy and arterial blood flow. The implications go further still, in that medical and medicinal aspects of this complex surgery probably benefited from the use of locally available tropical rainforest botanical resources to provide anaesthetics for pain relief and antimicrobial remedies to prevent infection,” she said.

The location of the find, too, is significant. In an article accompanying the study in Nature, Dilkes-Hall is quoted as saying that archaeologists once described southeast Asia “as a cultural backwater”. As it is, the recovery of human skeletal remains in this part of the world is “exceptionally rare”.

“Thus, we do not know if other societies in the area or more broadly across the Indo-Pacific region and in fact the world possessed knowledge of this nature as there is no other find like this to compare,” Dilkes-Hall told Hindustan Times.

“What we do know is that this find shatters long-held views and narratives formed from Eurocentric, racist, and sexist foundations, that have perpetuated the belief that societies who lived, and in some parts of the world continue to live, non-sedentary foraging lifeways (hunter-gatherer-fisher) were/are inferior to agricultural societies and not capable of the same medico-socio-cultural developments that have, until now, been confined to the Neolithic,” she said.