When parents abduct their own children

India is not a signatory of the 1980 Hague Convention that seeks to protect children from wrongful removal across international borders. But with increasing cases of parental child abduction, is it time for India to rethink its position on the treaty?

Fifteen-year-old Vividha is calm. She is standing in court number eight of the Supreme Court of India. Her parents are engaged in a custody battle over her. Lawyers engaged by her parents are embroiled in a heated argument over who should get her custody. Vividha raises her hand. She wants to speak. In clear words she paints in front of the court a memory from her growing-up years. It is a happy memory. Of a day spent at her maternal grandparents’ house with her mother. She is six, and she is just back from eating pao bhaaji with her mother. But that’s where the memory stops being happy. Vividha remembers her mother asking her whether she wants to live with her father or her mother. She remembers her perplexity over how to answer the question. She remembers answering that she wants both. And she remembers her mother angry and upset at her answer. She remembers her storming out of the room, banging the door behind her. “Who behaves like this with a six-year-old child,” she asks. Her voice is heavy with remembered hurt. Her careful composure breaks, as does her voice. Tears fill her eyes.

Vividha’s case is not just any custody batter. Vividha’s mother, Sapna is a British citizen who has alleged that Vividha’s father “abducted” the child and brought her to India in 2009. Sapna claims that the family was living in UK at the time and that Vividha was brought to India without her knowledge and permission. Sapna says that she has been fighting to take her daughter home since. But claims that in the years that her daughter has been away from her, her husband and his family has poisoned her daughter’s mind against her with the result that her daughter doesn’t want to live with her anymore. Her father’s lawyer meanwhile is trying to convince the judge that Vividha is well settled with him and should be allowed to continue as such.

In 1980 the Hague Convention drew up a multilateral treaty on the civil aspects of international child abduction. The aim of the treaty was to protect children from abduction and where it takes place, to create a system for their easy and quick return. According to the treaty, a child will be said to have been wrongly removed when the move is in violation of the rights of custody attributed to someone by the authorities of the country where the child has been living. Though the treaty doesn’t use the word “parental child abduction”, lawyer Anil Malhotra says it can be interpreted to be used in such cases. But only if both countries - the one of which the child was a resident and the one where he has been taken - have signed the treaty. Malhotra has over 30 years of experience in handling parental child abduction cases and has also written a book on the subject.

India has not signed the treaty. But with mounting international pressure, and faced with a growing number of such cases, the Ministry of Women and Child Development is scheduled to meet on February 3 to review its stand.

Gone for good?

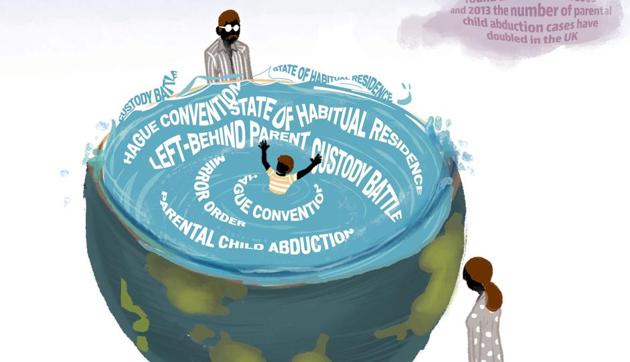

US resident Rakesh Agarwal says his son was “abducted” by wife and brought to India in 2012. Since then he has educated himself about the subject. As of August 2016 there were more than 80 cases of parental child abduction from the US to India, he says. India has the second highest number of such children being taken out of the US. And the number is growing, he says. “The year before India had the third highest number of such cases,” says Agarwal. US is not the only country from where children are being brought to India by parents trying to break out of a marriage while keeping the children with them. “India is among the top ten destinations where children are being taken to from UK,” says Vicky Mayes, development and external communications liaison officer, Reunite International Child Abduction Centre. The organisation was started by a group of mothers 30 years ago to support each other in their fight with their spouses to bring their children home. According to a study by the British government in 2013, the number of parental child abduction cases have doubled between 2003 and 2013. Reunite gets about 500 to 600 such cases every year, says Mayes.

The fact of the matter

India is among the top ten countries to which children abducted from UK are being taken by the abducting parent

A 2013 report found that between 2003 and 2013 the number of parental child abduction cases have doubled in UK.

India is number two on the list of countries to which children wrongfully removed from the US are being taken

According to US government data, there were more than 80 cases of parental child abduction cases from the US to India

The 1980 Hague Convention on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction seeks to protect children from the harmful effects of abduction and retention across international boundaries by providing a procedure to bring about their prompt return

The Law Commission of India has said that India should become a signatory of the Convention

In the US, Agarwal is part of a similar group called “Bring Our Kids Home”. A two-and-a-half-year-old organisation , it spreads awareness about parental child abduction. It also acts as a pressure group to bring in policy changes to address the issue. Agarwal alleges that when his wife left with their three-year-old son,he didn’t even hire a lawyer for six months. “I didn’t know about the Hague Convention. I didn’t know a parent can ‘abduct’ his or her child. I guess, I kept hoping that my wife will return with our son,” he says.

Agarwal remembers dropping his wife and son off at the airport in US. His wife’s sister was getting married and his wife and son were going to India for three weeks, he says. He was to join them in a week. “They were standing in queue for the security check and my son kept running back to where I was standing to hug me,” he says. Agarwal alleges that a few days before the family was to return to the US, his father got a call from his father-in-law informing him that Agarwal’s wife and son wouldn’t be going back to the US. While Agarwal admits that the marriage was troubled, his voice turns indignant as he insists that he had had no idea that his wife was planning to not return. “I tried to reason with her to return, or at least let me return to the US with my son, but she threatened me that I would be held responsible if anything happened to her,” he recalls. Agarwal claims that he took that as a threat to her life, and was coerced to leave his son in India. “I returned hoping that she would return once she cooled down. When she didn’t do so even after six months, I was forced to seek legal help,” says Agarwal.

Lawyers say that a family trip is often used as an excuse by parents to get the children out of the country of habitual residence. When marriages break down, children are the first to become collateral damage in the battle that almost always ensues over custody. When the battle spills beyond the borders of one country, it gets uglier and more complicated. As in every dispute there are, of course, two sides to the argument.

‘There is no rule of law. Decision is dependent completely on the discretion of the judge, and there are many stereotypes at work,’ says Deepti Khanna

There are many reasons for one parent to just take the child and disappear , instead of fighting a custody battle in the country of residence. One may do it when he or she fears that there is a stronger chance of the other parent getting custody of the child. Or when they are without the resources to fight a legal battle in the country of residence. They may feel they have a stronger support system in the country of origin and run away with the child to initiate legal proceedings there. Or , in case of a messy divorce, Malhotra says, the child is used by one parent against another to settle a score.

Malhotra handled his first parental child abduction case in 1986. The number of such cases in on the rise. With globalisation, as many more Indians move to live and work abroad, and marry outside the community , the number of such cases is on the rise. Malhotra estimates the growth to have been about three times in the last ten years. “On an average I get about three such cases every month,” he says. Since India is not a signatory of the Hague Convention, Malhotra says that parents who are trying to run away with their children feel India is safe haven for them. “It has given the country a bad name internationally,” he adds.

Not a custody battle

In the absence of proper laws a case of “abduction” by one parent, is treated as a case of custody battle in India, says Agarwal. If a country has signed the treaty, a court in the country where the child had been residing passes an order that a child be returned. The court in the country where the child has been brought to passes a mirror order. “This is not an order of custody. It just means that the child be taken back to the country of habitual residence where both parents may then file for custody,” explains Malhotra.

India is not only not a signatory of the Convention, but also does not yet recognise removal of child by a parent as an offence. Thus the only legal route open to the left-behind parent is to initiate legal proceedings in the country of habitual residence and then armed with the order from that court, come to India and file a case of Habeas Corpus in India. Once the child is produced in court, the case turns into a custody battle. “It is a long and slow process in India. Further there are very few lawyers in India who are aware of the law and who have the expertise to take on such cases. The cost to the left behind parent are sometimes prohibitive and they simply can’t afford to do so,” says Anne-Marie Hutchinson, a specialist in family law in the UK ,and an expert on the Hague Convention.

The in-between years

Time is crucial because of how it impacts the children. Anita Rastogi’s son was “abducted” by her husband as a toddler. She managed to get him back only after a search of four years. But it affected her relationship with him. “When he came back to me, he couldn’t accept my new partner and daughter,” says Rastogi. They underwent counselling and family therapy. But Rastogi rues, that though her son is a grown man now, her relationship with him continues to be strained. Left-behind parents allege that the year that the child spends away from them also gives time to the other parent to manipulate the child’s feelings against them.

‘Since India does not recognise parental child abduction as an offence, it becomes a custody battle in courts here,” says Rakesh Agarwal

India’s original reason for not signing the treaty, say some, was because the government felt that most cases of child removal are committed by women trying to escape a bad or abusive marriage in another country. Criminalising the act and forcing her to return to the country of habitual residence would therefore add to her problems. Mayes agrees that in 70% of cases, even today, it is the mother who removes the child. “But I don’t believe that it is a good argument anymore to not sign the treaty,” says Malhotra. Unlike in the eighties and nineties when a woman marrying outside the country was financially dependent on her spouse and had little access to resources, Malhotra says, today most women are employed, have access to the laws and are aware of their rights. To be a signatory to the Hague Convention, a country needs to have a domestic law on wrongful removal and retention of a child. In 2016 the Ministry of Women and Child Development drafted a Bill against parental child abduction. The Bill is available on the department’s website. But it is yet to be passed. The Law Commission of India has also advised that India become a signatory of the Hague Convention.

Steeped in stereotypes

In the absence of a law, Deepti Khanna, a US resident who alleges that her husband “abducted” their daughter in 2014, feels that the decision in favour of or against the left-behind parent “is dependent on the discretion of the judge. There is no rule of law. here are various kinds of stereotypes at work. Where the child has been removed by the mother, often the judge decides in her favour because the mother is believed to be the better caregiver. However, when the child has been removed by the father, there is often pressure on the mother to return to India for the sake of the family and stay with the child here. If you are reluctant to return, it is a count against you,” she says.

Her words might have been a summation of the battle being fought between Vividha’s parents. “The problem we are faced with is that you are in UK, and the child doesn’t want to go there. Can’t you return to India for a while,” the judge asks Vividha’s mother. Her mother pleads that they be allowed to return to UK, since the couple’s younger daughter is undergoing medical treatment in UK. The judge appears to be at a loss. Unlike “In such cases we have to also take into consideration the emotions of the various parties. I wonder whether I am even the right person to decide this,” he questions.