Sick of the stigma: Children with rare diseases who live a life apart

For kids with diseases that make them look different, social acceptance is tough and parents must work doubly hard to build confidence

Brothers Ashfaq Khan, 10, and Mushtaq Khan, 7, are the “ghost boys” of Rampur village in Vidisha district in Madhya Pradesh. They are routinely ridiculed, pelted with stones and have even had dogs set on them because they are different.

What sets them apart is not something they’ve done but the way they look. Both suffer from a rare genetic disease called Hypohidrotic Ectodermal Dysplasia (HED), which has manifested in four pointy teeth in their upper jaw, hair peppered with grey, flat noses, dark and cracked skin, and thin and reedy voices. “They couldn’t get an Aadhar card because their palms are too cracked (to get a biometric scan),” says their mother Abila Bi.

The brothers have no friends but each other and are shunned even by their extended family, which has ostracised their parents for giving birth to “ghosts”.

The parents, however, love their boys to bits. They resisted advice from ‘well-wishers’ to kill or abandon their firstborn Ashfaq after birth. When Mushtaq was born with the same disease, their extended family and villagers gave up on them and declared them cursed.

HED is one of around 150 types of ectodermal dysplasia that results in the abnormal development of the skin, hair, nails, teeth and sweat glands. The condition is life-threatening as affected children cannot sweat to regulate their body’s temperature.

“The disease can’t be cured but their sufferings can be reduced to some extent, but diagnosis is expensive as the medical tests for the HED type cost between Rs 35,000 and Rs 100,000,” says pediatrician Dr Gauri Pandit.

Watch Ashfaq and Mushtaq talk about their life

Tough diagnosis

Diagnosis is far from easy. “We somehow saved money for bus fare and took the boys to Guna and Bhopal, where doctors couldn’t diagnose the disease but made it clear to the villagers that they are not ghosts but suffer from an incurable disease,” says the children’s father, who works as a labourer.

Since the disease makes the boys feel exceedingly hot and the family can’t afford a fan, the two cool off by pouring water on themselves every half hour. They survive summers by staying indoors all day and stepping out only in the early morning and evening.

Having only four teeth in the upper jaws allows them to eat only food in a semi-liquid form. They have never tasted a fruit, not even the plums that grow wild around their village.

Three years ago, the brothers started attending school. They love every moment of it. “The teacher allows us to step out to pour water on ourselves and provides semi-liquid mid-day meals. We love to read with them,” said Ashfaq, who is Class 3 with his brother.

The only hurdle is social acceptance. “They looked like ghosts, I’m afraid of them. My mother asked me not to play with them,” said Shanu Khan, 8, a neighbour.

Read: Half of world’s disabled children are kept out of schools says report

Unwanted labels

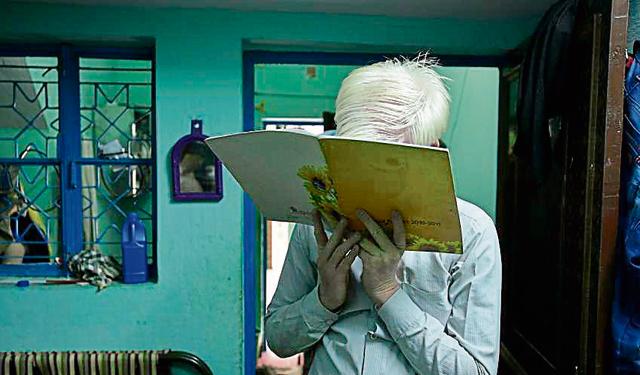

Delhi’s Pullan family also faces a hard time due to their fair skin; people label them as ‘Angrez’ because of their pale skin. They’re not foreigners but suffer from Albinism, a congenital disorder that results in complete or partial absence of melanin in the skin, hair and eyes.

“Life has not been easy for us,” Vijay Kumar, one of the six siblings, told HT. The family has struggled to get the colony kids to let them participate in games as children, to interact with the neighbours, find jobs and partners. They have also been called ‘Surajmukhi’, (a face like the sun) because of their extremely pale skin colour.

The mother, Mani, carries the gene from her family, while the father, Rose Turai, was the only one born with albinism in his clan. “We don’t have a choice. We just have to live with the discrimination,” says Vijay.

Heartbreak and hope

Mumbai’s Aarya Bhatkar, was one-and-a-half years old when he was diagnosed with Niemann-Pick disease, a rare type of Lysosomal Storage Disease (LSD) that is caused by genetic mutation and affects metabolism. Children with LSD have physical deformations depending upon the type of disorder. In some cases their bones grow abnormally, facial features can get coarser and the tongue may get enlarged, which makes it hard to function and harder to find acceptance among other kids.

“Aarya had an enlarged spleen, because of which his lower abdomen was bloated, his hands were twisted inwards and his feet never really grew after infancy,” says his mother Sheetal Bhatkar, a resident of Wadala, Mumbai. “Initially, my neighbour’s kids would come to play with him regularly, which he looked forward to. But, when his condition started deteriorating, they stopped visiting.”

Aarya took it hard. “He would ask me why they weren’t playing with him and I really had no answer,” says Bhatkar.

Her son passed away at age seven, two years ago, owing to the severity of his case, but Bhatkar is working to ensure that other children with rare disorders do not face the same stigma. She makes it a point to visit hospitals like KEM and Hinduja to talk to parents of other young patients on how they can cope and help their child deal with reactions from others.

Doctors too, refer parents to her so that she can counsel them on not losing heart. “One parent, whose child was battling a degenerative disease, called me up after I lost my son and told me that I must be relieved that the stress is over,” she recalls. “I was aghast, but then I realised that this stems from the social mindset about disorders like these. I explained to her that she needs to take things in her stride and do all that she can to make her daughter feel loved and accepted.”

Read: Tackling stigma- In Indore colony, HIV-positive patients live to the fullest