Where are the big cats? Curious case of Ranthambore’s missing tigers

Sundari had the advantage of pedigree. Born to the iconic ‘queen’ tigress of the Ranthambore Tiger Reserve (RTR), Machhli, she inherited her territory and fan following from her mother. So, when she suddenly disappeared from the reserve in March 2013, leaving three cubs in the lurch, 110 forest guards were deployed to find her. Ministers descended from the state capital “to handle the emergency”. The media launched its own hunt. Contrast this with the case of Indu. The tigress went missing from the reserve around the same time in almost similar circumstances. But nobody noticed.

“T-17 (Sundari) was the tigress of the tourism zone. She was much highlighted. We never heard of T-31’s (Indu’s) disappearance. Not even in our central meetings,” a forester, who did not wish to be named, told HT.

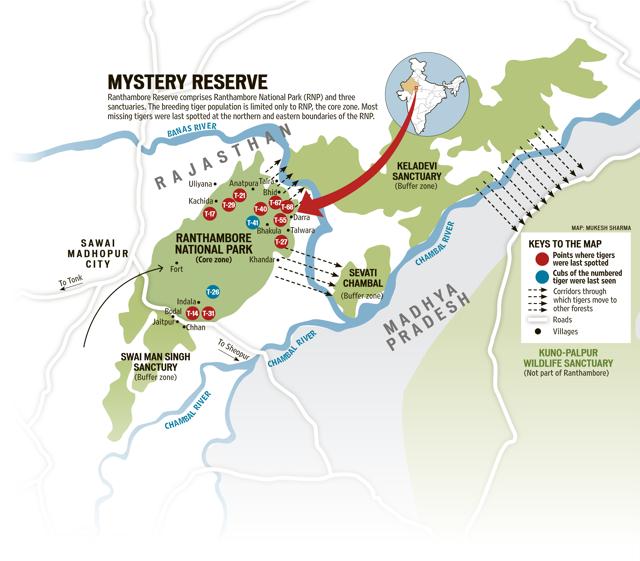

Indu is not alone. A Hindustan Times investigation reveals that in the past five years at least 12 tigers have mysteriously disappeared from RTR. This is equal to 25 per cent of the existing tiger population of the reserve. But unlike the uproar created over T-17 (Sundari), reports of other missing tigers -- belonging to the non-tourism zone of the reserve -- seem to have been quietly buried. To corroborate its findings, HT filed an RTI application with the Rajasthan Forest Department, pointing out the names of missing tigers and asking for the time and location of their last sightings. The RTI reply confirmed that 10 tigers had gone missing between 2010 and 2014 and have not been tracked, but was silent about the two other tigers. Nine of the missing tigers were young (less than 7 years old).

The revelation comes at the time when the Indian government is celebrating a “30 per cent” increase in tiger numbers in the country since 2011.

The RTR authorities downplay the vanishing of the tigers. “It cannot be conclusively said that tigers went missing. More and more tigers are moving out of the park to look for newterritories because the population in the park is increasing. It’s a positive sign. While the population of Ranthambhore National Park (RNP, the core area of the reserve) is constant the dispersing tigers might be populating newer territories,” said Y K Sahu, field director of RTR.

But, if the tigers are dispersing from RTR, do we know where they are going? Are we sure they are even alive to populate new areas? Not in the case of these 12 tigers at least.

Most missing tigers were last spotted at the peripheral areas of the RNP. While nine tigers went missing from the northern boundary, three disappeared from the south-eastern tip (see the map). This leads to the quick conclusion that the tigers might have dispersed through the corridors to the nearby sanctuaries. But the missing tigers do not feature in a recent study by the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF), which found records of 11 tigers dispersing from the RNP to the nearby forests and sanctuaries between 1999 and 2015.

So, what could have happened to the missing tigers? HT tracked the forests in and around RNP to look for answers.

The case files

Indu went missing from a big plateau called Indala Dang outside the eastern boundary of the park. Sahu attributed Indu’s disappearance to natural death. “It was an old tigress, about 12-13 years old. The dying of tigers due to old age or illness is as common as birth of new cubs. In most cases we don’t find the carcass because by nature tigers go to a secluded place to die naturally,” he said. Another forest official, however, informed us that the tigress was pushed out of its territory by one of its two daughters in a territorial fight. Tigers are territorial creatures and no two adult tigers or tigresses can live in the same territory; the weaker one has to move out.

A former forester, who retired from his service in early 2014, believed the tigress got poached once it was pushed out of the park. “Right below the plateau there are habitations notorious for hunting. A week before the tigress went missing there was a fight between the forest guard and residents of one of these villages. Within a few days, camera traps in the forest captured images of men with guns. The information was passed to the police but nothing was done,” he said.

Insiders in the forest department say Sundari might have also met the same fate. “After being pushed out from her territory in the tourism zone by a tiger, the tigress shifted to Kachida forests at the northern periphery of the park. She was injured and the department was feeding her and her cubs with bait. But another tiger fought with her in Kachida for the bait,” said a forester in the park. “The pug marks showed the tigress was pushed towards the villages where illegal stone mining is being carried out on the northern periphery. The miners might have poisoned the tigress,” he added.

A former poacher, now in his 60s, who was part of the infamous poaching network of Ranthambore till the 1980s, claimed Sundari died after being caught in a live wire trap that villagers near Kachida had put to protect their crops. “They buried the carcass to destroy the evidence,” he said.

The other disappearing tigers might have met the similar fate. A mutilated carcass of a tiger was found in Khandar in 2012 with half of its body parts missing. While it was difficult to figure out the gender of the carcass, the forest officials were quick to claim it could be the tigress T-27, who had gone missing in 2010. They claimed they saw pug marks of another tiger and concluded the big cat had died in a territorial fight. But a few months later this theory collapsed when a forensic report confirmed the tiger had died due to poisoning.

“If these tigers have not been photo-captured in camera traps or sighted in Ranthambore for such long time, and have not been recorded in the nearby forests, there is a huge possibility that they might have died. In the human dominated landscape outside Ranthambore it is very unlikely for a tiger to live unnoticed for such length of time,” said Ayan Sadhu, researcher at the Wildlife Institute of India, Dehradun who is conducting research on tigers of Ranthambore since 2011. “The death could be due to natural reasons, accidents, poaching or revenge killing by locals. None of the possibilities can be denied,” he added.

Poachers’ gain

RNP is ecologically a small area to accommodate large number of tigers. At 41 adult tigers (2014 census), scientists believe, the RNP tiger population has reached saturation point and has been so for the past few years. “Every year 5-7 cubs are born while 1-2 tigers die naturally. This means, 4-5 tigers are surplus every year who would be pushed out of the park,” said Sadhu.

While tiger protection is considered quite effective inside the RNP, the forest in the corridors and in the buffer zone is too fragmented to support a breeding tiger population, said Sunny Shah, team leader at the WWF office in Sawai Madhopur. “Due to poor connectivity with the next protected area, a lot of tigers who move out might be living in compromised habitat where they become easy targets for poachers. There are several settlements of poachers along the northern corridor towards Madhya Pradesh. Also, if tigers don’t find prey they kill livestock. The villagers then might kill the tiger in retaliation,” he added.

The WWF report has identified mining, increasing human pressure and poaching as possible threats to tigers in the surrounding areas. “Evidence of poaching was found on more than one occasion when survey teams encountered armed poachers in certain sites. Empty cartridge shells were also encountered during the sampling period,” says the report.

Residents of the villages Bodal and Gopalpura at the periphery of the park told HT that gun shots can be heard at night from nearby forests. “While most of the hunting is done by locals for subsistence, one or two tigers might be decimated every year by larger poaching networks. The forest guards here are not equipped to deal with poachers. They don’t have the will power. With several surplus tigers dispersing out of the park and being not sighted for months, hiding one or two cases of poaching becomes easy for everybody,” says the former poacher quoted earlier in the story.

Sahu admits to the possibility of poaching, albeit hesitantly. “Anything is possible. The forest departments (of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh) are aware that when a tiger moves out of its area, it is more vulnerable. We are doing what can be done,” he added.

Divided focus

Experts, however, feel enough is not being done to secure the dispersing tiger population. The WWF report recommends that the corridors connecting RNP to nearby parks and sanctuaries can be secured by regenerating forests and enhancing protection. However, till recently the RTR was being patrolled by half the number of guards required to cover the reserve. The 1335 sq km reserve has just 92 forest guards. The government has recently approved appointment of 132 more guards but the process will take time. While the protection measures are lagging behind, thriving tourism keeps the reserve management occupied.

Ranthambore is one of the most high-profile tiger reserves in the country. Project Tiger was first launched here. As tigers became the biggest tourist attraction of recent times, Ranthambore, with its small size and rising tiger numbers, has become a sought-after tiger-tourism destination. This has led to a massive investment in the tourism industry by land sharks. Hotels and resorts have mushroomed on every patch of saleable land. About 60 big resorts operating near RTR can accommodate about 3000 tourists, reveals forest department data. But on a given day only 1040 tourists can go inside the park according to its carrying capacity. This skewed ratio of demand and supply seems to have led to pervasive corruption in booking safaris.

On March 13, the Anti Corruption Department (ACD) of Rajasthan Police conducted a raid in the park. It found that 105 vehicles were plying inside the park at one time while only 80 are allowed according to the forest department’s own rules. The number of vehicles were almost double than the prescribed number in the zones which had a higher possibility of sightings.

Sahu denied irregularities. “We make exceptions to accommodate tourist pressure on some days. 105 vehicles are within the carrying capacity of the park,” he said. A source in the ACD, however, said a handful of hotels and their agents controlled the safari bookings and zone allotment. “Those who can pay money many times higher than the prescribed fee to their tour operators get a secured safari booking. If you want to go to the zone where chances of tiger sighting are higher, the charges will increase,” said the ACD source.

When HT visited the booking window, the scene was like a fish market. It was mostly the travel agents, guides and drivers who were negotiating tickets with the officers at the window. Tourist were not allowed by the agents to go ahead in the queue. Tickets and money are traded openly outside the windows by the agents, and accommodation deals for tourists are loudly negotiated over mobile phones.

Last month, conservationists raised concerns when the Rajasthan Forest Department announced its plans to start full-day safaris and night safaris in the park at higher charges. They said it would disturb the wildlife. Right now the safaris are conducted for three hours each in the morning and evening.

While the RTR makes news for its big plans on tourism, the stories of the missing tigers are quietly buried. The fact that most of the missing tigers are from the non-tourism zone might be more than just a coincidence. “There is a lot of money if, as a forester, you are posted on tourism management duty. On the other hand, there is hardly any incentive if you are on protection duty,” said a retired forester.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Taylor Swift, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.

Catch your daily dose of Fashion, Taylor Swift, Health, Festivals, Travel, Relationship, Recipe and all the other Latest Lifestyle News on Hindustan Times Website and APPs.