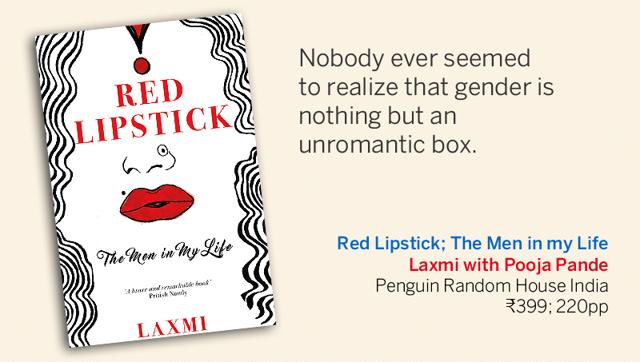

The Red Lipstick monologue: Laxmi speaks her mind in her new book

In her crackling new book, transgender activist Laxmi Narayan Tripathi writes about becoming a hijra, contemplates the idea of gender, and wonders about the mystery of femininity. An excerpt

When I was born, the doctor checked my genitals and pronounced me a boy.

Who could foretell that a claim like that, a seemingly innocuous gesture, would mark me for life?

What we’re assigned as at birth — male or female — is our gender. And somewhere along the way, we human beings decided that that gender would dictate our lives, steer us down certain paths, brand our behaviour, and inform almost all our choices—from something as trivial as the colour of your car to bigger decisions such as choosing a partner for life. Nobody ever seemed to realize that gender is nothing but an unromantic box.

And so it is that people like me, who fall nowhere in this binary, or somewhere in between, or even leap beyond — to me, the term ‘transgender’ has always implied ‘transcending gender’ — are considered misfits in society. We are termed ‘abnormal’, but as LGBT rights activist Ashok Row Kavi told me all those years ago when I, a boy myself, asked him why I liked men’s crotches: ‘The world around us is abnormal, baby. You are normal.’

Read more: Laxmi at the Jaipur Literature Festival 2016

As I was growing up, in the eyes of the world and those of my own family, I never gravitated towards ‘manly’ things. I loved to draw and paint, twirl around in lovely, flowy fabric, wear make-up and jewellery. My absolute passion, however, was dance. In dancing I was completely and utterly free. All of this meant, of course, that I was feminine. But the problem was that I was feminine despite being a boy. So when I wore bangles because they looked so good, red and shiny on my wrists, I would be told off by my friend’s mother. Everyone’s reactions around me seemed to indicate that I was acting like a girl, so I felt like a girl too. I would often refer to myself as one — ‘Main abhi aati hoon,’ I would say, and immediately be reprimanded for doing that. ‘Ladkiyon jaisi harkat mat kar (Don’t act like girls),’ I would be told. When I decided to grow my hair because long hair is beautiful, it really disturbed my father. He made sure I had it cut, because ‘Achche ghar ke ladke aise nahi karte (Boys from good households do not behave this way).’

The world kept suggesting I was a girl, but my private parts indicated that I was a boy. And then there was the whole question of sexuality. I was attracted to boys — my first inklings and stirrings of lust came from noticing big, strong arms, the hint of a guy’s moustache over his lips, billboards that advertised men’s underwear — and I was puzzled. Was there a woman inside me who couldn’t really express herself because of some last-minute mix-up that god did at the time of my birth?

Back then, in the early 1990s, the word ‘gay’ simply meant happy. Until one fine day, I was told that, in fact, that was who I was. Directed to Ashok for advice, I remember that day in Maheshwari Gardens so very well when seeing him and others like him and me around, I was overjoyed to have finally found an identity I could call mine wholeheartedly. I was not chhakka, mamu, god, or any of those terms hurled at me on a daily basis as abuses. I was gay. The world might still not like me for desiring someone of my own sex, but at least now there was certainty. For the first time in my life, I could set aside the crippling confusion and say to the world: ‘I am a gay man.’

The certainty did not last long. Now the world expected me to behave in yet another way — once again I was confronted with parameters and boundaries. I could wear shirts and pants, but I had to look and act ‘pansy’. And if I felt like wearing lipstick and a sari, it would mean I was ‘doing drag’. I just liked the feel of the sari, and the way it draped over my body. Does there really have to be more to it, I wondered. As a gay man, I was also always supposed to be ‘cruising’ other gay men — to be on the lookout for sex almost constantly. How exhausting! Is that any way to live? And why is it all only about sex?

I wondered about all this as I went on with my life, checking the boxes I was tagged under as a gay man, as a drag queen. But the question of my identity, that dialogue with myself, remained unanswered, unaddressed. Who am I when it’s just me, alone in my room? Who am I for the world? Are these two selves different, do they have to be?

I am thirty-seven today and, over the years, I don’t know if I have reached a place closer to the answer; I don’t know if I ever will. But if there is one identity I stay true to, it is the one that was created almost seamlessly — it is the Laxmi the world demanded when I went out to make my voice heard, to talk about the rights of transgenders. The persona of Laxmi the activist that was formed as much by the world I was interacting with, as by my own efforts. The supremely confident Laxmi who wears gorgeous saris, expensive make-up and perfume, who projects an image of absolute self-assurance, travels the length and breadth of the country and attends international conferences, gives speeches at queer pride parades, delivers TED Talks, is interviewed by the likes of Guernica and Salman Rushdie. So many doors that were closed to me, that were firmly shut, opened to this Laxmi. The creation of this persona has played an incredibly important role in my story, in the journey of my life — I began to enjoy being this Laxmi. And this Laxmi got things done. So she is as much for the world as for me.

If there is one role for me, the one big cause I know I am meant for, the raison d’être of my existence, it is that of an activist. I firmly believe that even if you have the best laws, unless you change the mindset of people, nothing will change. And that is what true activism means to me. That’s why I can never be a 9–5 activist, I don’t understand that, I am and can only be a 24/7 activist. Which is why, whatever the circumstances in my personal life, in public I have to be that — the Laxmi. Once I step out of my personal space, I cannot be merely myself. I have to be in the garb of that strong activist Laxmi because, inadvertently, I have come to represent a community of millions of people in this country. People look up to me and I have to fulfil the responsibilities of the role that has been given to me. No matter what I’m dealing with in my personal life, in public, I always go as Laxmi, the strong unbreakable activist nobody can mess with. In fact if I am going through a difficult time personally, I act even stronger when I don the persona. When I’m completely alone, all by myself, I’m not sure what feeling I am most comfortable with, who I feel is completely and only me. I ask myself many questions: Who am I? What am I? Then later I think, ‘Fuck it. I am Laxmi.’ That’s my persona; there is no room for doubt.

When Rama was leaving Ayodhya to begin his fourteen-year exile in the forest, such was his popularity, so great the devotion of his people towards him, that the entire kingdom followed him to the outskirts of the city. Touched by their support, Rama turned around and told his subjects, ‘I request all the men and women gathered here who truly love me, to please return to their homes. Once the duration of my exile is complete, I shall be back with you.’ At the completion of his exile, when Rama returned, he saw that there were several people still waiting at the same spot on the outskirts of Ayodhya where he had bid them farewell all those years ago. These were the hijras, my brethren, those who did not return to their homes, since Rama had implored only the men and women to do so and they were neither. Overwhelmed by their dedication, Rama granted them, and future generations of hijras, a boon — we would have the power to grant both blessings and curses to men and women, which would always come true. When hijras were patronized and indulged by royalty, they were not only visible but respected. It is this history and tradition of the hijra culture — rich, strong, textured — in our country that I found myself most drawn to. A tradition in which even the mighty, macho warrior Arjuna could don the garb and identity of a woman and become Brihannala effortlessly. A culture that offers us characters such as Shikhandi, the transgender who managed to thwart the invincible Bhishma. Where the ultimate male god, whose linga unmarried girls worship, praying and observing fasts for strong, able-bodied men as their husbands, also acknowledges his feminine self, and even embraces it, literally. They subsume within one another, fuse to become Shiva–Shakti—the Ardhanareshwara. A history that speaks of hijras in eminent positions, as political advisors to kings, administrators, generals, and guardians of harems.

Read more: A girl dreams of owning a green bicycle in Mridula Koshy’s new novel

I embraced the identity of hijra deliberately; it was a conscious choice I made, one that not too many understood. Why, after all, would a male child belonging to an affluent, upright Brahmin family initiate himself into a cult, a tradition, a section of society that’s much reviled by the mainstream? Why, indeed? It is seldom by choice that most hijras are hijras — it is, in fact, the lack of education and opportunities that forces many to find refuge in the hijra world. A lack that I, by the grace of god and my parents, never faced. So why would I, a privileged boy, become a hijra?

I was barely twenty when I met Lawrence Francis, aka Shabina, back in 1998. She was the first hijra I met and became close to. I used to work as a model coordinator in those days, and Shabina was the brother of a friend who worked as a model. Until then I was like any other person, frightened and somewhat repulsed by hijras. I met Shabina at the Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus station and coaxed her into going with me to Café Mondegar for a bite and a chat. I asked her many questions and learnt a lot about hijras in the process — the history, rituals, lifestyles, sources of income, the concept of gharanas, how your guru is like your parent, you are the chela, and it becomes a family. A few days later, I went to Byculla where the head of Shabina’s Lashkar gharana, Lata naik, held court. Nervous and unsure, I finally gathered the courage to ask those assembled there, ‘I want to become a chela. How much is the fee?’ To my surprise, they all burst out laughing. Lata guru, who went on to become my guru, said, ‘There is no fee, child. If you want to become my chela, come.’ My initiation ceremony, the reet, followed soon after—I was given two green saris, which are known as jogjanam saris signifying the inculcation into a new way of life, and crowned with the community dupatta.

Whenever I hear the term ‘transgender’, which we hear so often these days, I always feel that it implies ‘transcending gender’. Identifying as transgender, I connect with being hijra the most — the word ‘hij’ refers to a holy soul and the body in which it resides is ‘hijra’, hence they say the soul is hijra. As hijra, I can access both states of being — and I can also go beyond. In my strongest moments, I feel what a man feels, the power games that they like to play. And when I’m shining in my femininity, driving men crazy, I feel more like a woman than even the most womanly of women one could imagine. Like Cleopatra, or Umrao Jaan—both ultimate symbols of femininity.

I would really question things at one point. What is it about me that attracts men, I would wonder. These ‘straight’, patriarchal men. I am not a woman; I am feminine, but I am not a woman biologically, so what are these men about? So many men who’ve called me mother or sister have turned to me on an evening when they were drunk or when they thought I was drunk and have wanted to sleep with me. But I don’t need motherfuckers or sisterfuckers in my life. ‘Get the hell out of here!’ I would respond. They were ready to sacrifice everything to be in bed with me, even our relationship. I wondered then how that would happen — all these men were, in the eyes of the world and their own, heterosexual. And then I realized that the notion of heterosexual is, in itself, questionable. If you think about it, a woman is complete —she is XX and therefore complete. It is the man who is XY and hence has the woman in him. This ‘manliness’, then, is just a show, nothing but a convenient construct, a pretence to keep patriarchy alive, to keep women tamed. I am fortunate to be able to traverse through both genders so well. It is why I understand patriarchy inside out, and why I can empathize with the things women do, and how they think, act and behave.

Being a woman is so beautiful though — if I could always stay in that state of being, if I had the choice, I probably would. Again, I am not alone in this. Our heritage is full of stories that tell us how being a woman is a preferred state of being and existence. Take, for instance the story of King Bhangashvana, recounted in the Mahabharata, who lived his life both as a man and as a woman and who, when faced with the ultimate choice, opted to be a woman. And this was a king! There is also that unmistakable element of mystery about a woman, which is so alluring, which everyone wants and desires, and something that men can never experience. Tera charitra swayam Brahma nahi samajh paaye, they say — the Creator himself could not fathom womanhood and a woman’s character.

Being a woman is not easy in our culture, however. I often wonder how I come across as a woman. Slutty and available? Perhaps. But why? Is it because ever since I had the choice about my body and who I would give it to, I have only slept for pleasure? Or because I have opinions, strong ones, that I’m not scared to voice?

Women always have an image that men or the world constructs for them — it’s how they see them and how women see themselves. But that’s not how I feel. I think everyone creates their own parameters and boundaries and they live and function within them — charitra ke maap dand. And it’s the same for me. As far as I’m concerned, I am the Ganga, the holy Ganga. My purity cannot be measured by society’s standards. My purity is to my own self, to my own parameters. It is how I have conducted myself throughout my life and continue to. I decide my own standards and I abide by them. I have my own sense of integrity that’s very strong and in place, which nobody else has decided for me. My spirituality is to my soul, and it is for me. It should work for me. The world cannot have a say in that.