Translating Faiz over and again | Column

Translators will never tire of rendering the poetry of Faiz Ahmad Faiz into English, and here comes a fresh attempt that contextualises his work with the struggles of his time.

The first major translation of the poetry of legendary Faiz Ahmad Faiz into English came out in 1971. British Marxist historian Victor Kiernan introduced the revolutionary poet’s Urdu verses to the English world. There has been no stopping since then. This has something to do with Faiz’s everlasting appeal, who was to Urdu poetry in 20th century, what Ghalib was in the 19th and Mir Taqi Mir in the 18th century.

Of course, there were no trials and jails for Mir and Ghalib, neither was there any Lenin Peace Prize. Faiz saw this all and much more.

He took the genre of ghazal in Urdu poetry to new heights by aesthetically weaving in the dream of a new morrow within the given imagery of classical Urdu poetry. One recalls him telling a gathering of journalists and writers in the late 1970s in Chandigarh that if one did not use metaphors like zulf, paimana and mohabbat, the poem does not reach the masses.

Essentially a poets’ poet, the appeal of Faiz’s poetry was such that many longed-for translating his work into English. Those who have translated his verses include some well-known writers and poets from the sub-continent like Khushwant Singh, Shiv K Kumar, Vikram Seth, Shoaib Hashmi, among others. The sheer temptation to even attempt the hard task is remarkable.

In fact, playwright Shoaib Hashmi, who is married to Faiz’s daughter Salima, had an interesting anecdote about his father-in-law. When a friend told Faiz that a noted economist wanted to translate his poetry into English he just smiled and nodded, for he was as gentle as his poetry was fiery. When goaded to opine, he finally said, “Before you set out to translate poetry from one language to the other, you should make sure that you know at least one of the bloody languages!”

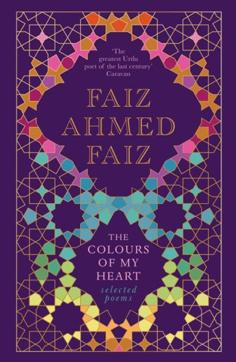

In this backdrop, ‘The Colours of My Heart’, the latest attempt to translate Faiz’s work into English reflects the finesse of a Persian carpet. The poems are selected and translated by Baran Farooqi, a seasoned translator and a professor of English at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi. Her work is distinct because she not only translates Faiz’s poems but also contextualises his work with the struggles of his time.

A look into the corridors of history suggests that Faiz lived in turbulent times. When he was blossoming as a poet in the mid 1930s, the nationalist fervour to gain independence was very strong. Besides, communal polarisation between the Hindus and Muslims was also gaining grounds.

Despite these, there were common platforms for the radicals and Faiz, like many others, was writing poetry and dreaming the colour of revolution-red. When independence was finally attained, a disappointed Faiz said, Intezar tha jiska yeh woh sehar to nahin (This is not the morn we were awaiting so eagerly for).

Describing the need to translate Faiz now, Farooqi says, “Today, when the word is in danger at the hands of demagogue, when individual’s dignity is at stake and freedom of speech at the risk of fast becoming an obsolete concept, we need Faiz’s poetry more than ever before.”

Indeed, Faiz stood for human dignity and when a Hindi publisher brought out his work in Devanagri, again in the 1970s, it was a mini revolution for those among us who did not read Urdu. Faiz was a much-loved poet of the sub-continent and not just of Pakistan.

Drifting back to that treasured evening hearing him talk with us in the city, I recall a tipsy scribe had said to him: “You belong more to Hindustan than Pakistan”. To this, the poet, who was aware of the consequence of nodding at such remarks, gently said, “By saying this, you make things difficult for us there. You belong here, I belong there. But let us keep meeting and exchanging messages of goodwill.” Amen!