Balbir Singh Senior: The legendary goal machine who defined an era of champions

Singh’s long and storied life tells us about hockey in India and about India itself.

The death of Balbir Singh Senior does not mark the end of an era. The era in question had long disappeared in a vortex of fevered imagination and half-remembered truths. The man himself had seen it disappear. He had tried to alert others to the fact more than forty years ago but, like Cassandra, he had gone unheeded. That is why his death is a great loss: we never understood what we had.

If the average Indian remembers Singh today - if we remember him at all in the midst of the pandemic - it will be as a talismanic goal-scorer from the time when newly independent India won the hockey gold in three consecutive Olympic Games. The historically minded will savour the neat symmetry of it all, for the sequence mirrored the Olympic exploits of the hockey teams from British India in the inter-war years when the ur-Indian centre-forward, Dhyan Chand, reigned supreme.

Also Read | Balbir Singh Senior was a legend across the border too

Close followers of the game will also recall Singh’s role in the background of India’s triumph in the 1975 Hockey World Cup, the last tournament before international hockey replaced grass with artificial playing surface. Talk of the pre-Astroturf era may prompt the mischievous to make jokes about how India had been the one-eyed king in the land of the blind. After Partition, the other eye went to Pakistan who did not do too badly either, they will add. The confused may express surprise that Balbir Singh died twice when in fact it was his younger namesake who passed away in February.

All these different points of view will miss the essential import of Singh’s long and storied life and what it tells us about hockey in India and about India itself.

The colonial legacy

Singh and others from the first batch of Indian hockey heroes were products of colonialism. The way of life in a British-ruled colony conditioned them to take up a sport like hockey. Colonial-era institutions, whether sympathetic or opposed to the British Empire, gave them the opportunity to nurture their skills.

Also Read| ‘Saw Balbir Singh cry like a child after defeat to Pakistan’

A strong domestic structure with roots going back to the beginning of the twentieth century allowed them make a career out of the game. They had an earlier generation of players, some of them world beaters, to learn from. And they had able administrators, from the ranks of both the rulers and the ruled, to support them.

The bare bones of Singh’s life story fit the narrative. That he started playing hockey in the town of Moga in East Punjab points to the spread of the game beyond the big cities and traditional centres, in Punjab in particular and across British India in general. After his failure in the F.A. examinations in Moga, he could carry on with his education at Sikh National College, Lahore, and later at Khalsa College, Amritsar, because he was an outstanding hockey player. And it was his hockey skills that got him a job in law enforcement.

Sir John Bennett, the Inspector-General of Police, Punjab, knew a good hockey player when he saw one. Others who shaped Singh’s career included Harbail Singh, whom he first met when the latter was coach at Khalsa College, and Dickie Carr, an Anglo-Indian from Kharagpur and a gold medal winner at the 1932 Los Angeles Olympics, at whose insistence Singh was called up to the 1948 trials in Bombay.

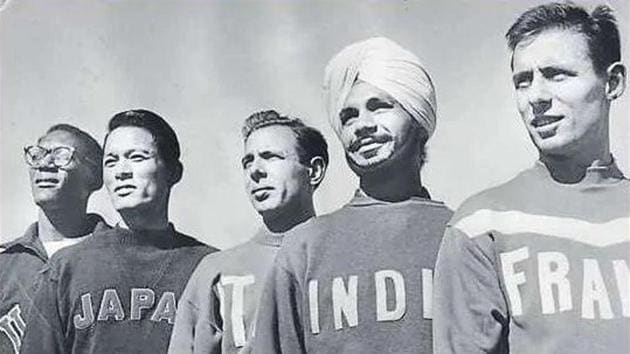

A team-man to the end of his life, Singh would not have disputed the fact that he was not an outlier. Taking the example of the 1948 India squad sent to London: apart from a large contingent from Bombay, it included players who spent a considerable part of their formative years in big cities like Lahore (Keshav Chandra Datt and Tarlochan Singh), Delhi (Jaswant Singh Rajput), Bangalore (Walter D’Souza) and Madras (Ranganathan Francis).

But there were others who had learnt their hockey in smaller centres like Faisalabad (Grahanandan Singh), Naini Tal (Pat Jansen), Bhopal (Akhtar Hussain and Latif-ur-Rehman), Jubbulpore (Gerry Glacken), Mhow (Kishan Lal, the captain) and Kharagpur (Leslie Claudius). Their love for the game had been variously nurtured by Anglo-Indian schools, colleges, civilian clubs, helpful seniors and sympathetic administrators. A number of players from that era found employment in government services, which had been the bulwark of British rule in India.

These facts are not stated to undermine the thrill felt by the players when they got the opportunity to represent the tri-colour in London in 1948, about which Singh had spoken eloquently. And independent India rightly reaped the benefits of what this fine generation of hockey players achieved for the country. However, it is equally important to understand the legacy they had inherited, a legacy that independent India failed to protect beyond a point.

Early struggles

Of course, as Indians coming to maturity in and around 1947, Singh’s generation had to negotiate a world marked by both continuity and change, including the seminal events of Independence and Partition, the brutality of which Singh, as a policeman in Punjab, saw from close quarters. There were other, minor discontinuities that had to be dealt with. The 12-year Olympic hiatus forced by the Second World War meant free India could no longer call upon any player from Dhyan Chand’s generation. A fresh challenge had to be mounted with new players. India was fortunate that hockey had continued in the country uninterrupted through the war years but meanwhile the standard of hockey across the world had also improved. And of course, there was Pakistan.

The players had their individual demons to deal with too. Looking back at India’s Olympic domination in the decade after independence, it is tempting to imagine that it came all too easily. However, behind every triumph lay stories of individual and collective struggle. For example, it is rarely remembered that Claudius, who would go on to win three Olympic gold medals and one silver, played only one match in London. He was considered too small to be effective in the heavy grounds of England.

It was no different for Singh. Tucked away in Dhyan Chand’s memoirs, Goal!, published in 1952, is a comment about the Indian centre-forwards of the time. “It is a pity,” writes Dhyan Chand, “That we have no outstanding centre-forward to-day. That is my opinion. What we have to-day is a company of mediocrities amongst whom I would include Balbir Singh of East Punjab.” As a player and a coach, Singh made many critics eat their words. One would like to imagine that Dhyan Chand would have agreed to do the same by the time Singh ended his playing career.

A warning that went unheeded

What allowed players like Singh and Claudius to overcome such obstacles early in their careers was the robust system that produced and supported Indian hockey players. And this is what Singh had seen disappearing before his eyes. In 1977, he wrote, in collaboration with sports journalist Samuel Banerjee, an autobiography, The Golden Hat Trick: My Hockey Days. In the foreword, Banerjee writes: “(Balbir Singh’s) only concern was whether the printed word would draw more youngsters to our dying hockey tradition.” India were still the World Cup holders, but had missed out on an Olympic semi-final spot for the first time in Montreal in 1976. Singh could already see the end.

He was not the first. Twenty years earlier, in 1957, Father Daniel Donnelly, rector at St Stanislaus School, Bombay, had identified the main threats to India’s hockey supremacy: the failure of schools to foster the game and falling spectatorship at hockey matches. Donnelly’s clear-sighted analysis had implicated, without naming, government officials, educators and hockey administrators in India’s failure to protect its hockey legacy. What made Singh different was that he had shown, in 1975, that he had a solution.

Of course, Singh would have been the first to point out that he had help from like-minded individuals and, more importantly, he had the trust of the players who executed his plans to perfection. If only Indian hockey administrators had reposed similar faith in the man in the decades that followed. The advent of Astroturf, and its scarcity in India, would have arguably created a new obstacle in his path. However, from what we know of Singh, on the field and off it, he would have likely found a way past it.

(The writer is a former journalist whose doctoral thesis was on the role of Anglo-Indian community in Indian hockey)