How to implement Agnipath properly

A solid and long-term vision is required to roll out the plan. In addition, the scheme must be constantly evaluated to remove the rough edges and make changes, based on feedback

The government has finally announced the details of the much-debated short-term recruitment policy for the armed forces called Agnipath. With the formal decision behind us, let us examine the plan’s facets and their impact on those who want to join the services.

The scheme will be open to those within the 17.5 to 21 age bracket. They will join the armed forces on a four-year contractual service and will go through an intensive 24-week-long training. Though numbers will vary in the future, 40,000 will join the Indian Army, 3,000 the Indian Air Force, and 3,000 the Indian Navy. The Army may take 170,000 in the first four years. This number may vary later, depending on the requirement. The armed forces will eventually absorb only 25% of the initial intake.

The soldiers (agniveers) will receive ₹30,000 per month and an annual increment of up to ₹3,500. Of ₹30,000, ₹9,000 will be deducted for the Agnipath Corpus Fund, with an equal contribution from the government. On completion of the “tour of duty”, an agniveer will get severance pay of ₹11.7 lakh, though he will not be entitled to a pension.

In addition, an agniveer will be insured for ₹48 lakh by the government, and covered under an ex-gratia grant of ₹44 lakh on being a battle casualty. A similarly graded disability package and salary for the unserved portion for the soldier or their next of kin has been planned.

The scheme is undoubtedly a massive change from the existing intake format in the armed forces. The government has taken into cognisance a large number of recommendations. The scheme now has a single tenure of four years, a commensurate insurance scheme, and built-in variables to adjust to the circumstances and experience gained.

There are three significant effects of Agnipath that need examination.

First, what would be the outcome for aspirants after four years? There will be a substantial number of aspirants who would like to be in the armed forces. They will hope to become permanent or obtain the severance pay and placements. Hence the government has to envisage a “whole-of-government” approach to create avenues for those who complete four years under the new scheme. There is immense scope in home, railways, and industry ministries to absorb the well-trained, disciplined, and experienced but younger workforce. The armed forces can also help in placements. Banks have been advised to provide guarantees for small business loans (to add to the severance package). Therefore, the anxiety surrounding the possibility of a young soldier being unemployed and out on the streets needs to be allayed.

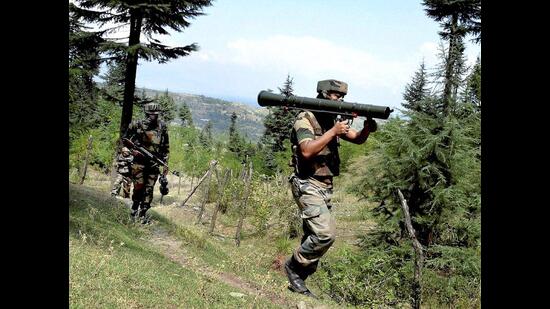

Second, what impact will Agnipath have on the armed forces, especially the manpower-intensive Army, and the infantry that is stretched on the northern borders and in Jammu and Kashmir? There is the anxiety of creating a “passersby” culture in an organisation that is built on discipline.

An infantry unit will get about 30 to 35 recruits a year, which, in four years will mean about 100 agniveers. Subsequently, less than 10 will be held back permanently in a unit annually. For an infantry battalion, with a good unit tarteeb — the bedrock of effective man-management and administration — should be able to integrate 50 intake-offtakes on a yearly basis. The Rashtriya Rifles is an excellent example of efficient turnover of manpower without sacrificing operational efficiency.

The All India-All Class (AIAC) — under which soldiers are recruited without any region-specific criteria — is another issue that is a worry for the largely north Indian single-class composed regiments. Currently, roughly three-fourths of the recruitment is from an all-India pool and a fourth for region-specific regiments (such as the Jat regiment). Therefore, stricter adherence to a national intake, based on the recruitable male population, may have an effect on combat arms over a period of time.

Apparently, the culture of the regiments will not be affected. Between 30 to 35 AIAC soldiers — of which a number may well be from the single class — will join the infantry battalions annually. A back-of-the-envelope calculation shows that in 10 years of the scheme, about 125 AIAC soldiers will be in infantry units. Again, with the basic character of the regiments unchanged, units will have to integrate and operate as one.

The third is the question of optimisation of the forces. As the existing shortfall in manpower is unlikely to be recouped, the armed forces must work on force optimisation.

India has two adversaries, with disputed borders. There is also an optimal necessity for investing in modern warfare — domains such as rockets or missiles, drones, counter-drone technology, modern platforms, cyber, space, and electronic warfare. Many of these domains do not fall under the ambit of the military. There is also the issue of integration of the three services. The forces need to optimise themselves for combat power than address optimisation on a manpower basis. Optimisation of combat power mandates careful sectoral considerations on “how will we fight”, with what, to what end, and for that, what tri-service and national capabilities are required. Therefore, this study of optimisation of combat power is most important and must emanate from the national security strategy.

Agnipath has far-reaching implications. The armed forces are revered national institutions, the ultimate source of hard power, and have a critical role to perform. Therefore, a solid and long-term vision is required to implement Agnipath. In addition, the scheme must be constantly evaluated to remove the rough edges and implement the feedback. Rigidity needs to be obviated, and sufficient dynamism built in.

Lt Gen (Dr) Rakesh Sharma commanded the Fire and Fury Corps in Ladakh responsible for Kargil, Siachen Glacier and Eastern Ladakh. He is currently a distinguished fellow at Vivekananda International Foundation (VIF) and Centre for Land Warfare Studies (CLAWS). The views expressed are personal

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website