How to build a new innovation structure

The Rama Rao-Hamied- CSIR bond made HIV/AIDS drug accessible. To succeed, they broke the walls between scientific institutions, researchers and industry. This must now happen routinely

India is one of the world’s largest producers of what are called generic drugs. When pharmaceutical companies develop new drugs, they usually patent them. When patents expire, it is possible for other manufacturers to make the equivalent drug and market it. This is the niche Indian companies have very effectively occupied.

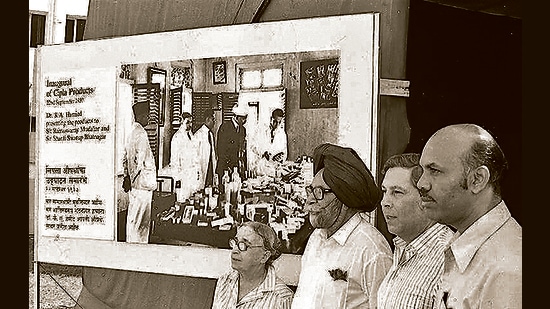

This has been a difficult accomplishment and a result of the intelligence, zeal and commitment of individuals, institutions, and the industry. Equivalence with branded drugs, high standards, and quality control are vital for acceptance. There is arguably a no better example of this than how Yusuf Hamied of Cipla provided the world with an affordable cocktail of anti-HIV/AIDS drugs.

Sometime in 1988, AV Rama Rao, then at the Council of Scientific and Industrial Research’s (CSIR) National Chemical Laboratory (NCL) in Pune, came across a news item about a 13-year-old boy dying due to HIV/AIDS. Rama Rao decided to act. Azidothymidine (AZT) was the only drug available at the time and was extremely expensive. Rama Rao improved on the known process and approached Hamied, who he knew well from an earlier collaboration.

“My friend at the National Chemical Laboratory was a gentleman called Dr Rama Rao; he assisted us with the development of many raw materials. He is still very active today, even at the age of seventy-eight [still active at 87 now], and I am still in touch with him. One day in 1991, Rama Rao came to me and said, ‘Yusuf, I’ve developed a synthesis for AZT, zidovudine, and the government has allowed me to collect the starting material beta thymidine, which can be imported without duty in India’,” said Hamied in a 2013 interview to Tarun Khanna as part of the book Leadership to Last: How Great Leaders Leave Legacies Behind, by Khanna and Geoffery Jones.

Rama Rao had also applied to the drug controller for review and a permit for manufacturing. Cipla started distributing this drug at only $1 a tablet, many times lower than the international price. Soon Cipla added other drugs to make a cocktail, again for $1 a day, saving millions of lives all over the world. While other industries were potential competition, the matter was one of astuteness in taking the business leap and of trust in Rama Rao’s daring. Hamied said, “If Rama Rao wouldn’t have come to me with this in 1991, I might not have taken it up.”

Rama Rao (born 1935) was one of 12 siblings and grew up in Guntur, Andhra Pradesh. Education meant the hope of a job, and failure meant poverty. As a chemistry student, employment as a demonstrator in the same college was a lifetime sinecure. But Rama Rao left that and went to Mumbai for his PhD at the university’s Institute of Chemical Technology (ICT), a great institution. He then went to NCL, another great institution, where Raghunath Mashelkar was the director when Rama Rao’s Cipla interactions took place. Rama Rao now runs AVRA Laboratories that do research and development of active pharmaceutical ingredients.

Hamied’s life could not have been more different. His Indian father and Lithuanian mother met in pre-war Vilnius, now in Lithuania, where he was born in 1936. Hamied studied chemistry too, did his undergraduate studies and PhD in Cambridge, England. Today, he is also well-known as a benefactor of research and collaborations between India and the United Kingdom.

The story of how a young man from Guntur whose spirit and drive matured in great institutions and made him seek out motivated scientist-industrialists needs to be heard by scientists, bureaucrats, and youth. It is a special Indian love story.

Much of this happened through turns of fate, individual motivation, and institutional permissiveness. This must now happen routinely and freely, for which enabling processes of collaboration between institutions, with universities, and with the industry must be absorbed and implemented. Top national laboratories of CSIR (NCL, Indian Institute of Chemical Technology, Central Drug Research Institute), Mumbai University’s ICT, the department of pharmaceutical’s National Institute of Pharmaceutical Education and Research, and pharma departments in universities must have collaborate in research that complement their strengths while valuing their diverse approaches. Early-stage research also depends heavily on computational approaches. Tools for this need to be developed, and we must not only import plug-and-play applications. For drug development to move from generics to innovation animal trials and “first-in-human” trials will have to be amplified here, in partnership with the industry.

Our strengths in the organic chemistry of generic drug development have come from the efforts of several scientists, usually determined men working on difficult problems. Determined women — such as Asima Chatterjee (1917-2006) and Darshan Ranganathan (1941-2001) for example — have faced greater odds and yet excelled. The next generation of drug innovators needs greater diversity.

We have a thriving drug and pharma industry, with dozens of companies such as Cipla.

We have international companies investing in India for chemistry and computational approaches to drug discovery. All of these are staffed by talented Indian students. On these broad shoulders, we can build a new structure of innovation and discovery, which is globally competitive and original. There will be many more triple bonds of researchers, institutions, and industry.

K VijayRaghavan is the principal scientific adviser to the Government of India. In this column, we celebrate the 75th year of our Independence and remember our great scientists, institutions, and scientific achievements even as we introspect and look to the next 25 years The views expressed are personal

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website