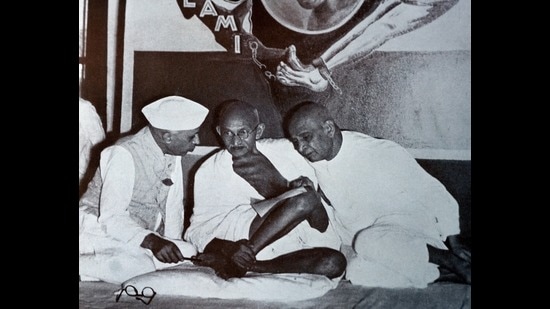

Gandhi’s two lieutenants: Panditji and the Sardar

Let no one suggest that Nehru and Patel weren’t different or didn’t differ. But let no one deny that they overcame those differences for the majesty of India

Sardar Patel, our first home minister and deputy prime minister was 75 when he died, in 1950. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, our first prime minister (PM), was also 75 when he died, in 1964. October 31 is Patel’s birth anniversary. In a fortnight from now, it will be Nehru’s.

No two persons could have more different; no two stalwarts of India’s freedom struggle more inseparable. Like pen and cap, letter and envelope.

Nehru’s letters written from prison to his daughter are famous. The lifafas (envelopes) Patel made under Mahatma Gandhi’s supervision in Yeravada prison are less known, but were “something else”.

The older of the two was born to the sinews of husbandry, tough and real in the sense in which the earth is real, droughts are real and the hoe and plough are real. And peasant resistance to unfair exactions of land revenue and taxes from them is real. Patel led two amazing peasant satyagrahas in Kheda (1918) and Bardoli (1928), to resounding success, earning the epithet of Sardar. And so when as the minister in-charge of the integration of the princely states into the new Indian Union, he knew that princely India was entitled to respect, not power in the new order. That now resided in the people who instinctively trusted Gandhi.

Patel was as much part of Gandhi as his charkha was. One drew strength from the other, organically. The very name, Sardar Patel, has strength to it, character, and a sense of no nonsense. Seeing him in control, India’s sons and daughters felt they were in safe hands.

Pandit Nehru, the younger of the two foremost associates of Gandhi, was made of the essence of the thinking mind, the analytic historian’s global mind and the philosophic enquirer’s universal mind. It was as sensitive as people’s feelings under colonial domination, imperial exploitation and feudal immiseration. Born to comfort, he doffed its appurtenances to become one with the people whose cause he made his own, rebelling against his aristocratic father’s ambitious vision for his only barrister son.

Casting his lot with Gandhi, he stayed true to his own sense of where India should be headed in the 20th century as a free nation.

Nehru was as much part of Gandhi as his famous watch was. One kept time with the other’s step. The very title “Panditji” sent heartbeats of excitement through the masses. Seeing him in their midst, the sons and daughters of India saw a deliverer, a liberator.

Patel and Nehru were inseparable in the history of our freedom struggle. India needed them together, said Gandhi, as a cart does its two bullocks. Both knew they were, within themselves, very different.

No cart, no bonding.

But the cart, India, was right there.

In his last conversation with a disturbed Patel on January 30, 1948, in Birla House, New Delhi, minutes before he was assassinated, Gandhi heard his comrade describe his differences with Nehru and his readiness to quit. There is no “official” record of that conversation, but, from all accounts, it is clear Gandhi told Patel his presence in the Cabinet was indispensable as was Nehru’s.

Patel returned to his house, as Gandhi walked to the prayer ground and to his death. News reached Patel and Nehru within minutes. Patel got back to Birla House a few moments before Nehru who, Rajmohan Gandhi tells us in his biography of Patel, “went down on his knees, put his head next to Gandhi’s and cried like a child”. He then put his head in Patel’s lap.

Nehru’s words, “The light has gone out of our lives” belong to literature. Patel’s belong to reality. “The mad youth who killed him was wrong if he thought that thereby he was destroying his noble mission.”

Amid calls for Patel’s resignation as home minister, and revived whispers on their differences, Nehru wrote to his senior colleague three days later: “With Bapu’s death, everything is changed…I have been greatly distressed by the persistence of whispers and rumors about you and me, magnifying out of all proportion any differences we may have…We must put an end to this mischief.”

And Patel responded, “I am deeply touched, indeed overwhelmed, by the warmth and affection of your letter…We both have been lifelong comrades in a common cause. The paramount interests of our country and our mutual love have held us together…”

When, in January 1950, on India becoming a Republic, he was demitting office as India’s last Governor-General, Chakravarti Rajagopalachari, was given a farewell banquet. Sentiments of sadness at his departure were expressed by the leaders present. PM Nehru and deputy prime minister Patel facing him at the table, Rajaji said in his reply: “The Prime Minister and his first colleague, the Deputy Prime Minister, together, make a possession which makes India rich in every sense of the term. The former commands universal love, the latter universal confidence. Not a tear need be shed for anyone going as long as these two stand foursquare against the hard winds to which our country may be exposed.”

The operative word in that observation was “universal”. That, of course, was poetic license. Nehru did not command the love of the Hindu fanatic. Patel did not enjoy the confidence of the Muslim bigot. And yet, the statement was broadly true. The two did converge in the overwhelmingly large middle ground that existed between the two communities — a fact which Right-wingers in both sections would want to deny today. And both knew this. They knew too that though they were very different, but mutually antagonistic polar opposites, they were not.

Patel was to say on October 2, 1950: “I have been referred to as the Deputy Prime Minister. I never think of myself in these terms. Jawaharlal Nehru is our leader. Bapu appointed him as his successor and had even proclaimed him as such. It is the duty of all Bapu’s soldiers to carry out his bequest. Whoever does not do so from the heart in the proper spirit, will be a sinner before God.” When Patel died within a few weeks of that, Nehru spoke of him as one who had “revived wavering hearts”.

Patel and Nehru stand on the same page today, validating Rajaji’s words, reviving our confidence in one and our love of the other.

Let no one suggest the Patel-Nehru differences dissolved in the meltdown of Gandhi’s assassination. They did not. But let no one deny that those differences were overcome by these two great sons of India for the majesty of our country. India needs confidence in its greatness which cannot exist without a love for its uniting spirit.

Gopalkrishna Gandhi is a former administrator, diplomat and governorThe views expressed are personal

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website