Diwali’s visual archive - lights on the canvas

Indians have celebrated Diwali with lights, but also with art of all kinds (from folk art to miniatures), reflecting the different forms the festival takes in the country

It was a day like no other.

Since the morning, Ayodhya’s air was thick with anticipation and taut with excitement. King Dasharath’s eldest son, Ram, wife, Sita, and his brother, Lakshman, were returning to Ayodhya after 14 years in exile. Those 14 years had been action-packed, and ended when Ram’s divine arrow pierced the heart of Ravana, the hydra-headed demon, in faraway Lanka, in a do-or-die battle. By the time the day eased into the inky autumn night, the kingdom was wrapped in a golden hue. As the resplendent chariots of the first family rolled in, Ayodhya, lit up by rows and rows of clay lamps, erupted in celebrations. It was Diwali, or Deepawali (“row of lamps”).

Since that day, the festival is celebrated in India – now even in other parts of the world – with great vigour and enthusiasm. But, in the cultural kaleidoscope that is India, there is no single template for Diwali, which gives it a pan-Indian flavour and an inclusive appeal. Unsurprisingly then, Diwali is also depicted in different ways in India’s rich repertoire of visual arts. “You’ll find exquisite paintings dedicated to Diwali, all the more striking because it is deepening dusk and the indigo skies are alight with stars, so it is also the most idyllic setting for lovers enjoying the festival. We see tribal artists celebrating Diwali with rituals unique to their rites of worship,” says art curator Ina Puri.

All inclusive

Even though it is a Hindu festival, the Mughal dynasty, with its roots in central Asia, took to Diwali in a big way. The Rang Mahal in Delhi’s Red Fort was the designated area for the royal celebrations of Jashn-e-Chiraghan (festival of lights), and the festivities were carried out under the watchful eyes of the king himself. Fireworks were organised in the fort’s vicinity, and the palace was lit with diyas, chandeliers, chiraghdaans (lamp stands), and faanooses (pedestal chandeliers).

In many 18th century paintings (Mughal, Pahari and Rajasthani), bejewelled men and ladies are depicted lighting lamps and enjoying a variety of fireworks. “While looking at these paintings, however, one should be careful because all paintings depicting fireworks are not about Diwali. Fireworks were widely used to celebrate weddings and processions too,” explains art historian, Naman Ahuja. In the late 1700s, as the British East India Company tightened its grip on India, the festival of Diwali, with accompanying descriptions of atishbaazi, began to surface in many paintings, in a genre known as the Company style. If the north of the country is all about lights, fireworks, teen patti, and Lakshmi puja on Diwali, in the east it’s Kali Pujo, though there is no link between the two festivals. However, like Diwali, the theme of good over evil runs through Kali Pujo also.

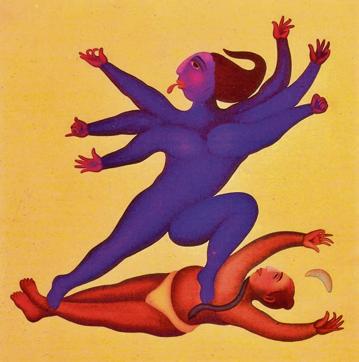

“Kali Pujo is restricted to the East, mainly Bengal, Assam and Orissa. It is on the 14th day of the lunar calendar, which coincidentally falls during Diwali. Kali is the malevolent form of the goddess, who kills the evil forces, in the form of dacoits and demons. She is the one who helps Durga kill the demon Raktabija, by drinking the demon’s blood, because every drop of blood that fell on the ground gave rise to more of his kind,” says mythologist, Utkarsh Patel.

It’s a coincidence and with the intermingling of people from different regions, it [Diwali] has blended in the cultural ethos of the modern-day Indian. So it is not unusual to find Bengalis lighting diyas and bursting crackers on Diwali, and visiting the houses of non-Bengalis when they perform Lakshmi Puja. (Prosperity was linked to Ram Rajya. So Diwali is the celebration of Ram’s return, when prosperity [Lakshmi] comes back).

Different expressions

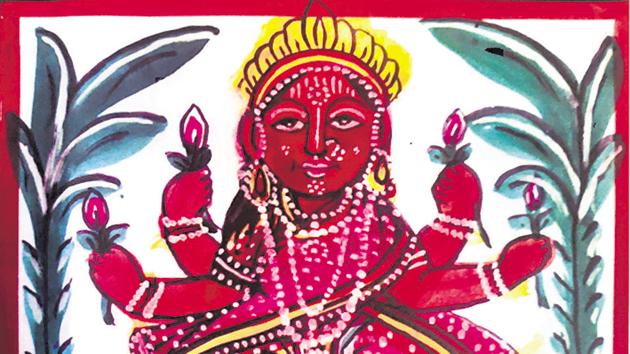

“The Pattachitra [cloth-based scroll painting] painters of the east portray Kali as she is worshipped in the region, while the Gond artists have their own artistic expressions... be it the veneration of Kali or Deepawali, the artists have their way of celebrating shakti and the festival of lights,” adds Puri.

In the south, where some of the mythological stories connected to the festival come from the north, Deepawali is celebrated a day before the festival in the north, with lots of light, less noise (though this is also changing). On the no-moon night (amavasya), the goddess of wealth is venerated.

There are several Indian folk-art forms and traditions (Mandana, Chitera and Thapa) that are drawn/painted during Diwali.

The Mandana paintings of Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh are done by women who chalk-paint their houses with different designs during the festival season. The root design of a ‘Deepawali ka Mandana’ is invariably enclosed within a circle or a series of lines drawn parallel to the lines and angles of the original design. The Thapa drawings – the stamping done by the palm of the hands – entail certain ritual observances. The Thapas of Lakshmi depict the goddess seated on a lotus or with a lotus in her hand, and is done with vermillion.

Chitera or Chitravan are wall paintings done by professional painters (mostly men from Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan). They draw inspiration from religious narratives. During Diwali, Lakshmi is depicted seated on a lotus, and either two or four elephants are shown to be bathing her with a kalash held in their trunks. In other parts of India, such artworks are also known as aripan and rangoli. “This has strong religious, moral and cultural aspects for the communities that draw/paint them,” explains Molly Kaushal, head, Janapada Sampada Division, Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, Delhi.

Over the years, Diwali has become synonymous more with fireworks than lights. With rising awareness about pollution, it’s time to return to its original form, and make it exclusively a festival of lights, and the arts.

Around the world in Diwali stamps

In 2016, the 2.5 million-strong Indian-American community in the US won a major victory. After campaigning for two decades, which included garnering support of three Democrat legislators, Carolyn B Maloney, Ami Bera, and Grace Meng, the US Postal Service, which gets around 40,000 requests for issuing stamps to highlight various issues and accepts 25, finally released a special Diwali stamp.

The beauty of the 2016 campaign was that it went beyond being a demand of the Indian-Americans. “It is not about the celebration of a religion or a nation. It is about universal values of inclusiveness,” Ranju Batra, chair, Diwali Stamp Project, had told the media back then. Once the sale of the stamp, the first to commemorate Hinduism, was announced, it opened the floodgates of demand. Five people ordered stamps worth $10,000, and soon postal offices ran out of stock. Over 20 countries supported the gesture to commemorate the release of the stamp. In 2018, the United Nations Postal Administration issued a special stamp sheet to commemorate Diwali. Each stamp sheet has 10 stamps with diyas and lights in various colours.

“The struggle between Good & Evil happens everyday @UN. Thank you @UNStamps for portraying our common quest for the triumph of Good over Evil in your 1st set of Diwali stamps on the occasion of the auspicious Festival of Lights,” India’s Permanent Representative to the UN, Ambassador Syed Akbaruddin, had tweeted. Over the years, many other nations, which have a strong Indian diaspora, such as Singapore, Australia, and Canada have also issued Diwali stamps.

“The issuance of stamps signifies the importance of India and its culture. It also spreads the deeper message of the festival, which is about togetherness and joy,” says Rajesh Kumar Bagri, secretary general, the Philatelic Congress of India.