Can you name India’s classical dance forms? We bet you missed this one

Sattriya is a vibrant, ancient classical form from Assam. But it was only recently recognised by the Sangeet Natak Akademi and is still struggling to find space on the national stage.

Nestling in the heart of South Delhi is the Srimanta Sankaradeva Bhawan under the Assam Association of Delhi. From its façade, a giant mural of two traditional Assamese performers watches over everyone walking through its gates. As you make your way to the first floor, you catch snatches of Assamese and beautiful aromas from the kitchen.

The overwhelming tranquility of the place cuts it off from the bustle outside, making it stand apart like an island — much like the river island of Majuli in Assam, which is synonymous with the dance form celebrated by this institute, Sattriya.

“In keeping with the beautiful philosophy of Srimanta Sankaradeva, we dance and sing… Now I understand that this work is an act of spiritualism, a mission, a thought process, and a journey into discovering the self — this is what Srimanta Sankaradeva taught us,” says Bhabananda Barbayan, founder and adhyapak (teacher) of Sattriya dance at Srimanta Sankaradeva Bhawan.

Originating and deriving its name from the ‘sattras’ or Vaishnavite monasteries of Assam, Sattriya, the dance, was introduced by the 15th century neo-Vaishnavite poet-saint Sankaradeva. As this Vaishnavite Bhakti movement gathered momentum in Assam, the sattras began to be recognised as spiritual, artistic and cultural seats of the state. In present-day Assam, there are over 900 sattras divided among four orders, or Sanghatis, which emerged after Sankaradeva’s death, amid rifts between disciples vying to succeed him.

ON STAGE

The origin of Sattriya lies in the theatre form of Ankia Naat, attributed to 15th century poet-saint Sankaradeva.

These were plays crafted as a way of reenacting episodes from the life of Krishna, considered the most complete avatar of Vishnu.

The dance form is marked by lilting and sprightly movements, often reminiscent of “the waves of the Brahmaputra,” according to Sattriya scholar Arshiya Sethi.

Instruments like the khol terracotta drum, the flute and the cymbals accompany a traditional Sattriya performance.

Costumes include dhoti, chadar and the paguri or turban for male characters, and ghuri or skirt, chadar and kanchi or loincloth for female characters.

Colours in a traditional performance are generally restricted to white, red and gold. In recent years, performers have been seen embracing other vibrant colours on stage as well.

Until recently, monks were the sole exponents of the dance, with performances led by a sattradhikari or sattra chief in the naamghar or prayer hall. It was only in the 1920s that women began to be included, following an initiative by Pitambar Dev Goswami, one of the most significant social reformers of Assam and sattradhikari of the Garamur Sattra.

Later, the inclusion of women in the performing spaces was given a bigger thrust with Rasheswar Saikia Barbayan, another Sattriya stalwart, setting up the Sangeet Sattra (earlier, the Bayanor School) in Guwahati in 1968, to train women and, eventually, take Sattriya out of the sattras. To this day, though, only the male monks are allowed to perform in the naamghar. Women are the principle flagbearers of the dance form on the public stage.

***

Although this is a rich living tradition with a history going back 500 years, it was only as recently as the year 2000 that Sattriya was recognised as one of the major traditional, or ‘classical’, dances of India, by the Sangeet Natak Akademi — the apex body for the performing arts in India, directly under the centre’s Ministry of Culture.

Among the eight ‘classical’ dances of India, Bharatnatyam, Kathak, Kathakali and Manipuri received the titles first, followed by Odissi, Kuchipudi and Mohini Attam. In India, the ideas of what make for a “classical” art form still draw from the Natyashastra, a Sanskrit text believed to have been compiled by Bharata Muni around 200 BCE.

The ancient temple and court dances of India were incorporated into the Natyashastra, and followed its guidelines of Nrittya, Natya, Bhava and Rasa (roughly, Movement, Drama, Emotion and Aesthetic). The intended purpose of the dance plays a role too. The dance forms which the Sangeet Natak Akademi recognises as classical fall under the category of Maargi (ones that show the path), as opposed to desi or folk dance forms, again drawing on the conventions prescribed by the Natyashastra.

Bharatnatyam got its classical tag first. “This gave it first-mover advantage,” says Arshiya Sethi, a scholar whose research focuses on Sattriya and its politics. “The whole process of nomenclature is a politically ridden process. A name can’t be more politically ridden than the term ‘Bharatnatyam’,” she adds.

In an essay, Odissi exponent and scholar Ananya Chatterjea says that not only did “Sadir’s renaming as Bharatanatyam (have) its own symbolic weight”, but because Bharatnatyam was the first to claim classical status, “it effectively set a clear model for how ‘classicism’ might be interpreted” with respect to the Indian dances.

Interestingly, there seems to be a lack of acceptance and understanding of this politics in the dances as we see them today, Sethi adds. “One of the groups that refuses to see it like this is the dancers themselves.”

***

It was Maheswar Neog, an eminent Assamese scholar and authority on Sattriya heritage, who first argued for Sattriya to be included in the classical pantheon, at a seminar organised in Delhi in 1958 by the Sangeet Natak Akademi.

“At the time, Shanti Dev Ghosh of Santiniketan too supported the idea of Sattriya being recognised as classical. In fact, he even advanced the proposition that the origin of Manipuri lay in Sattriya dance,” Sethi says in her research. However, Sattriya still failed to make the cut; Odissi, Kuchipudi and Mohini Attam raced past it to the finish line. Soon after, an expert committee was set up by the government in response to a demand put forward at the same seminar. The committee included Neog, Sanskrit scholar and musicologist V Raghavan, and Rukmini Devi Arundale, the legendary exponent of Bharatanatyam.

In 1959, on their recommendation, Sattriya artistes were made eligible for Sangeet Natak Akademi awards, but under the ‘other traditional dance forms’ category.

Why it took another 41 years to get the coveted tag “is difficult to explain, because there isn’t any written documentation as to why it happened,” says Anwesa Mahanta, an Ustad Bismillah Khan Yuva Puraskar awardee for Sattriya and currently a resident artiste at IIT-Guwahati. “A lot of work still needs to be done because not many people still know about Sattriya,” Mahanta says.

A simple Google search for Sattriya training institutes in Delhi shows the Assam Association as the only legitimate result. This isn’t the only challenge facing the dance form today. Mahanta attributes the lack of widely accessible literature and scholarship in the Sattriya arts as another reason for its slow growth in popularity.

On account of the knowledge being passed on orally from one generation of monks to the next, “Sattriya was in its own zone… We do have shlokas and written theatre traditions by the saint poets, but mostly you’ll see that the repertoire of the dance numbers is in Assamese or Brajabali, not even Sanskrit. Most research was also done in Assamese. Even now, not much is being done on Sattriya in English,” Mahanta says, adding that she too suffered due to a lack of resources while conducting field work for her research.

***

The language barrier and geographic isolation of Assam played important roles in deciding Sattriya’s destiny, as did the politics of the movement. From its inception, the sattras and Sattriya adopted an anti-establishment stance, denouncing all animal sacrifice and the caste system. And then the politics of the state vis-à-vis the Indian state came into play.

Soon after independence, the massive Province of Assam (which also included the princely states of Manipur and Tripura) began to be broken up. In the hopes of pacifying the hostile, refractory tribes in these new states, the Centre left Assam to deal with the largest chunk of the population, on a gradually shrinking piece of land.

The next few decades saw the riverine state slowly turn into a conflict zone amid the growth of regional militant groups and an influx of migrants from Bangladesh. The Indian state continued to look the other way, whether in terms of economic policy or coercive measures taken on the pretext of security concerns.

The political situation in Assam reached its boiling point when the major insurgent group, the United Liberation Front for Asom (ULFA), demanded separation from the Indian state. Soon after, then prime minister Rajiv Gandhi signed the highly contested Assam Accord, in 1985, in which the union government promised to “renew their commitment for the speedy all round economic development of Assam as to improve the standard of living of the people.”

“In the accord, the Union government had, in a sense, accepted the charge of neglect of Assam,” says the Sattriya scholar Sethi. Thereafter began a rather obvious attempt at ‘corrective federalism’, as Sethi calls it, with infrastructure set up, awards instituted and statues installed to reflect the culture of Assam in the state and in the national Capital.

When the Srimanta Sankaradeva Kalakshetra was set up in Guwahati in 1998, it was inaugurated by then President of India KR Narayanan. Later that year, the iconic Assamese singer song-writer Bhupen Hazarika was appointed chairperson of the Sangeet Natak Akademi. The culmination of all these individual moments finally led to Sattriya being declared a ‘classical’ dance on November 16, 2000, under the chairmanship of Hazarika, in a general body meeting held in Guwahati — the first held outside Delhi since the Akademi had been set up in 1952.

As the noted dance historian and Padma Shri awardee Sunil Kothari wrote in his obituary for Hazarika, “Thanks to Bhupenda’s initiative, finally Sattriya dances received recognition as a classical dance form along with other dance forms. And after 2000, the dancers practising Sattriya dances never looked back.”

***

They now had a spot on the national stage, but practitioners of the dance continue to struggle to take their art beyond the monasteries. Bhabananda Barbayan currently trains 35 students at Srimanta Sankaradeva Bhawan in Delhi and another 25 at a centre in Gurugram. Almost all are Assamese; Bhabananda admits that they “need some non-Assamese students” if the form is to gain a more diverse audience.

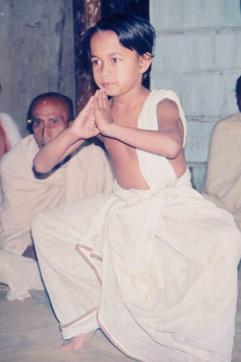

Bhabananda, who is from the Uttar Kamalabari Sattra of Assam, has trained in the Sattriya arts as a monk, since the age of three. He eventually stepped out of his monastery to embrace a larger, more public stage, and went on to pursue a PhD on Sattriya from Rabindra Bharati University in West Bengal. He travelled abroad for the first time in 2008, to France and Portugal, and staged 36 performances at 18 cultural festivals. “It was a huge success for Sattriya,” he says, with a hint of a smile.

Anwesa Mahanta, the award-winning exponent, blames a lack of government initiative to recognise and harness Assam’s magnificent cultural heritage as “cultural diplomacy, or even cultural tourism”.

“Not a single fellowship is awarded to practitioners to pursue their work, forget about research,” she says. “The government remembers the Sattriya dance only when there is a delegation arriving and they want a 15-minutes performance,” she adds.

“The government remembers the Sattriya dance only when there is a delegation arriving and they want a 15-minutes performance,” says award-winning Sattriya exponent Anwesa Mahanta (above).

Raju Das, deputy secretary of the Sangeet Natak Akademi and director of the Sattriya Kendra in Guwahati, says continuous efforts are being made by authorities to popularise the dance form “at every level”.

“We organise many festivals outside Assam, for example at Benaras Hindu University, in Karnataka, at Pune University; we organised one in collaboration with Symbiosis. The Bhartiya Vidya Bhavan University in Pune has also started a course in Sattriya… We also sponsor artistes outside Assam. Apart from that, we are also funding research and publications,” he says.

He believes maintaining the sanctity of the living tradition is essential to its growth, and the dilution of the form by some upcoming artistes, who practise their “own style”, needs to be strictly monitored.

The art has adapted as it moved to embrace women, and platforms outside the monasteries. In fact, there is now concern over the dropping number of male exponents. “Discriminating between a man and a woman performer wouldn’t be fair because both can perform with equal finesse,” says Prerona Bhuyan, co-founder of the US based Sattriya Dance Company. “But with every passing generation, the number of male performers is diminishing.”

Perhaps, as Sethi says, “Sattriya needs to not only assimilate, but also ‘Assam’ilate itself”.