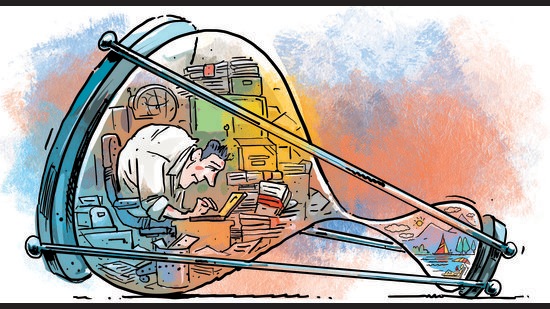

When will it be our turn to log out?

Indians continue to top the lists for most time spent at work and least on vacation. Countries with far better rankings were once here too. How did they turn things around, and can we?

In the future, people might work just 15 hours a week, economist John Maynard Keynes predicted 90 years ago. His essay was titled Economic Possibilities for Our Grandchildren. Well, the grandkids are here and everyone’s still devoting at least three times as much time to work as Keynes predicted, and that’s not even accounting for the boom in work hours since the pandemic hit.

Why blame Keynes? It’s been a century of cheery predictions about how humans will need to work less as technology and productivity boom. These predictions have been issued by economists, management experts, scientists and science-fiction writers.

And yet around the world studies show that lower- and middle-income countries tend to work long hours for low pay, amid heightened job insecurity. India routinely features in the top 5 or 10 countries in the world when it comes to the number of hours put in each week. And in the bottom 5 or 10 when it comes to vacation days taken.

In the most recent International Labour Organization (ILO) report, released in February, India came in at #5 on the list of countries with the longest work weeks (48 hours a week on average). Only Qatar, Mongolia, Gambia and the Maldives ranked above us.

The Netherlands and Denmark, at the other end of the spectrum, have average work weeks of 37.3 and 37.2 hours respectively, according to a 2021 report by the US-based think tank World Population Review.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development or OECD’s latest Better Life Index ranks countries by how well citizens are able to juggle work and personal life and it found that only 0.4% of employees work over 50 hours a week in the Netherlands.

It wasn’t always like this for them either. Economic theory suggests that long work weeks are a phase most economies must go through before they emerge on the other side — slower but wealthier and more stable. However, work culture plays a major role too. “In Europe, though the economy is highly developed, it’s also an economy of greater leisure,” says Sumangala Damodaran, professor of economics and development studies at Ambedkar University, Delhi.

Countries such as Germany pride themselves on the productivity that allows their economy to grow healthily and remain stable at one of the shortest working-hour averages in the world — 39.5 hours a week. That’s not even eight hours a day, five days a week, and in India you’d be told off as a slacker if you tried it for a single week.

“Ours is a hangover from the19th-century industrial mindset that more hours equal greater production,” says KR Shyam Sundar, professor at the XLRI – Xavier School of Management in Jamshedpur. We never moved on from the idea of production to the concept of productivity, he adds. “A longer course of work is still equated with economic efficiency which is not exactly true.”

How this will evolve amid and after the pandemic is unclear. Working from home could eventually push India’s work culture towards a better balance with life. Or it could continue, as it has been doing since March, to make work even more all-pervasive.

The consideration of work-life balance has become even more critical since the onset of Covid-19, says Sundar. It is a question for legislators too, he adds. “Working from home is affecting workers and their families, culture as well as leisure time. Work arrangements are also getting distorted in ways that allow employers to capitalise on the vulnerability of the person who needs the income in an uncertain time.”

In South Korea, which had a similar work culture of long hours in a rapidly growing economy, the grind is now seen as the source of some of the country’s most looming social issues, including low birth rates. In 2017, the country’s president Moon Jae-in pushed to legally reduce the country’s working hours and give workers the “right to rest”. In 2019, a new law reduced the maximum number of working hours per week from 68 to 52. A year earlier, then Japanese prime minister Shinzo Abe launched a similar campaign there.

“The mainstream economic logic is to first achieve progress and then fairness,” says Sundar. And the change from this mindset is never spontaneous. “As in Europe, companies must set up self-regulatory rules and regulations,” Sundar says. “But eventually, the onus will lie on the government.”