What purpose do dreams serve? The science is stranger than the fantasy fiction

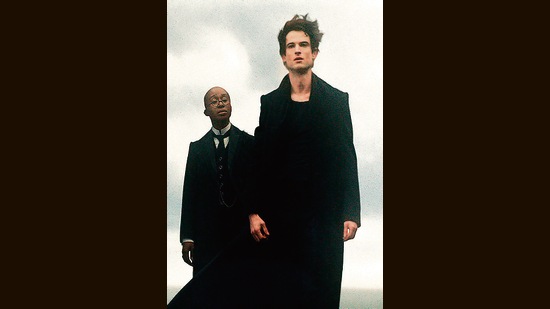

One man’s nightmares gave us The Sandman, a world in which the creator of all dreams struggles to control them. That’s the popular comic, now also a Netflix show. But what does the latest science say, about the abiding mystery of why we dream?

The writer Neil Gaiman has often talked about how he had terrible nightmares as a child; dreams that would leave him terrified, in a cold sweat. Where most of us would shake off the feeling and lull ourselves back to sleep, Gaiman says he flipped the script. He began to jot down what he’d been dreaming about — fragments of a scene, a half-formed villain, the mood, the cause of the terror — and he began to use those notes to write fantasy fiction.

The nightmares went away soon enough, he said, in an August 5 interview with Time magazine, as his cult comic, The Sandman, was released as a 10-episode adaptation on Netflix (a 11th bonus episode with two stories that form part of the Sandman canon dropped later). “My eventual theory was that whoever was giving me them was so disappointed by my reaction to them that they just couldn’t be bothered anymore.”

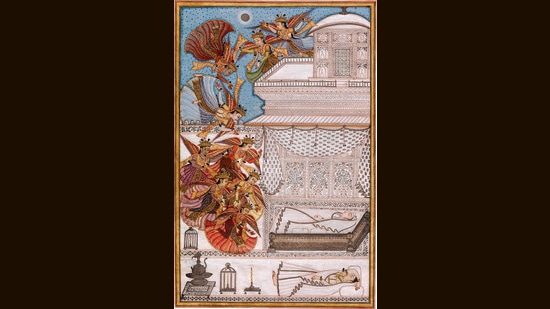

The Sandman was first published by DC Comics in 1989. By the following decade, the adventures of the dream-controlling Morpheus, who has to rebuild his empire, regain his magical possessions, and recapture errant dreams and nightmares after 70 years in captivity (the show makes this over a century), had turned Gaiman into a literary superstar. The show is dark; but it is rich in its depth of narrative; and almost magical in its imagination. But much of its appeal lies in its treatment of that blurry world of sleep where anything is possible and none of the normal rules apply.

On average, we spend about two hours each night dreaming. We know we dream largely during the rapid-eye movement (REM) stage of sleep, a period when brain activity is as high as when we’re awake. We suspect that other mammals, birds and reptiles dream too. Foetuses appear to dream as well. It now turns out that spiders might dream too.

We don’t yet know why we dream. It might be humankind’s longest-running mystery. Every culture, in every age, has found ways to make sense of where we go in our minds when we sleep. There are those that see dreams as a means of connecting with the divine, or receiving messages from the beyond. Psychologists tend to believe that dreams are the subconscious, reaching out to the waking self.

Dreams have also long been sources of inspiration. From Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s Kubla Khan to James Cameron’s Terminator, elaborate imagined worlds have entered our world through dreams (as have mundane things, such as the structure of Benzene, dreamed by chemist August Kekule ) Could our world be a dream? That’s the premise of Christopher Nolan’s 2010 film Inception, and there are schools of philosophy that would agree.

Who knows what dreams can become if they are released into the world. For now, take a look at what we now know about dreams. The science of why our brains might be taking us on these wild journeys is almost more fascinating than the fantasy.

- Rachel Lopez

.

A filing system for the mind

Antonio Zadra was a young dream researcher when a neighbour told him a story that changed the course of his work. This neighbour had a dream, she said, about falling through the wooden staircase that led to her second-floor home. A few days later, a wooden step did collapse under her, and she narrowly escaped a serious fall.

The neighbour couldn’t understand how her dream could have “predicted” this. She’d had no reason to suspect the stairs were rotten. Zadra took the same stairs and they’d seemed fine to him too. But Zadra knew that as humans we perceive only a small fraction of the information that our brains absorb from the world around us. He came to the conclusion that his neighbour had subconsciously registered a rotting stair, and her dream had been a reflection of this information, now registered in her subconscious.

In his most recent book, When Brains Dream (2020), Zadra and his co-author Robert Stickgold, a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, propose that dreams are, in fact, not expressions of secret wishes, fears or hopes, but simply a unique form of memory processing.

The biological function of dreams, they argue, is to allow the brain to scan its memory, extract information, and embed it into long-term storage. This could also explain, for instance, why we sometimes wake with forgotten to-dos floating to the surface.

Should one be scanning one’s dreams, then, for signs of the future? Zadra and Stickgold are emphatic that one should not. It is very rare to find that kind of direct correlation.

Instead, they say, their model can be explained by the acronym NEXTUP (Network Exploration to Understand Possibilities). In simple words, a primary function of dreaming is to detect and dramatise the possible meanings of information latent in memories. The sleeping brain has its own way of doing this, using associations that we rarely access while awake. Part of this process, for instance, involves linking and cross-referencing new information with old memories.

Over time, the sleeping brain’s associations form a web. Within this web, narratives form. They make sense to the sleeping-but-busy brain; to us, awake, it’s just the world of dreams.

.

The recurring nightmare

For the lucky few, recurring dreams feature food or sex. But most recurring dreams, studies have found, involve the dreamer being in danger. Common themes include being chased, being naked in public, losing one’s teeth, and riding a tsunami.

Why do dreams recur, and why along these lines?

Studies suggest that part of the function of dreams is to help humans process the experiences and emotions of their day, particularly in times of stress. Dreaming is even described as “overnight therapy” in a 2009 study by sleep researchers from the University of California, Berkeley, published in the journal Psychological Bulletin. The amygdala, a brain area associated with emotion, and the hippocampus, a brain area associated with memory, are both reactivated during the REM sleep stage in which most dreams occur, this study found.

How close is the concurrence of stress and recurring dreams? A 2002 study of students’ dreams in the run-up to exam season found that the incidence of recurring dreams shot up in this period, particularly among those with a history of recurring dreams.

The study was conducted among a group of 39 students (aged 18 to 50), in the week prior to a midterm exam. The findings from that first phase of the study were then compared with a second phase conducted with the same students in a regular midsemester week. It was found that students had considerably more recurring dreams in the stress-filled pre-exam weeks.

The stress associated with recurring dreams is probably why most such dreams involve the dreamer feeling helpless or vulnerable, states the study, conducted by researchers Theresa Duke and John Davidson of the University of Tasmania, and published in the Journal Dreaming.

.

Vitamin B6 to help remember dreams?

New research suggests that a dose of Vitamin B6 could help sleepers better remember their dreams.

For their study, dream researchers at the University of Adelaide asked 50 adults to take a B6 supplement before bed for five consecutive days; a control group of 50 others took a placebo Vitamin B-complex pill, containing a variety of B vitamins.

According to the findings published in the journal Perceptual and Motor Skills, those who took the B6 pills were better able to recall the content of their dreams, remembering 64.1% more dream content than the group that took the B-complex.

“It seems as time went on my dreams were clearer and clearer and easier to remember,” said one participant. “I also did not lose fragments as the day went on.”

What applications could this information have? Denholm Aspy, lead author of the study, points out that having greater recall helps people achieve the phenomenon of lucid dreams, which occur when a person is consciously aware that they are dreaming within a dream. And lucid dreaming has been found to help reduce nightmares, particularly in people with post-traumatic stress disorder. It has also been shown to help treat certain phobias. “It is critical to first be able to recall dreams on a regular basis in order to have lucid dreams,” Aspy said in a statement. “This study suggests that Vitamin B6 may help.”

.

Fly on the wall to a spider’s dreams

Does one need a spine, in order to dream? Spiders are throwing down the gauntlet in this regard, forcing researchers to rethink how they view the dream world.

So far, it was thought that only mammals, birds and certain reptiles could have REM sleep, which, in humans, is the phase linked to dreaming. Then it turned out that cephalopods such as octopi also exhibit signs of REM-like sleep. Now, a study published in August in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggests that a species of jumping spider might be a dreamer too.

A team of researchers at the University of Konstanz in Germany reported that a group of 34 juvenile Evarcha arcuata jumping spiders all exhibited signs of REM-like sleep, when studied at night via infrared camera.

It all began in 2020, when behavioural ecologist Daniela C Roessler returned home from dinner one night to find her jumping spiders dangling from the lids of their boxes. Roessler, who had brought the spiders home because her lab was inaccessible during the pandemic, thought they’d all died. It turned out she just hadn’t studied them by night; this was merely how they slept.

Intrigued and wondering what else she might learn about their sleep habits, she added a new angle to her existing study, which had been testing the spiders’ response to 3D-printed predatory spider models. She decided to film the spiders as they slept. In reviewing the footage, she noticed the spiders’ interior retinal tubes shaking rapidly. Could this be REM sleep, in an arachnid?

As Roessler and her team investigated further, they noted that the young Evarcha arcuata’s retinal movements were accompanied by a twitching of the legs, as they hung upside-down. “The twitches seemed so classical. They immediately reminded me of a dog dreaming,” Roessler told The Washington Post in August.

The next phase of research will seek to establish that what Roessler calls “REM-like sleep” in her study report is in fact REM sleep. As with other species, signs of REM sleep would then be compared with changes in brain activity or physical movements to assume dream states, since there is no way to know for sure if any of these species dreams.

.

Are dreams a form of cerebral disruption?

Could dreams be the brain’s way of reprogramming itself? A paper published in the journal Patterns in May proposes that dreams are the brain’s way of breaking out of a rut and keeping itself alert to new ways of thinking — in much the same way as random data is used to teach computers to recognise and respond to new patterns.

In his study, Erik Hoel, a neuroscientist and assistant professor at Tufts University in Boston, refers to his concept as the “overfitted brain hypothesis”. It is partly inspired by a common problem in training artificial intelligence. When AI becomes overly familiar with the data on which it has been trained, it begins to believe that the training set is a perfect representation of everything it will encounter. This can render the program “overfit” — capable of doing one thing extremely well but unable to “learn” or process information that could be applied to other tasks.

To avoid this, programmers frequently introduce random variables, or noise, into the data. Hoel argues that the human brain does something similar, through dreaming. In essence, he says, dreams are the brain’s way of counteracting the familiarity of everyday tasks, a form of disruption or noise added to its data, in order to keep itself fit, flexible, and more alert and responsive to change.

It’s why we sometimes awake with a solution to a nagging problem, he adds in his study. It’s possible that the waking brain had become overfitted for the task; the sleeping brain, with its dream scenarios, was able to offer much-needed disruption, and voila, a new approach was found. “This fits with... the long-standing traditional association between dreams and creativity,” Hoel says in a Tufts University blog.

Neuroscience research already supports the overfitted brain hypothesis, Hoel states. For instance, it has been demonstrated that the most reliable way to elicit dreams is to perform a task over and over prior to sleeping. Hoel argues that this works because repeating a task over and over constitutes over-training, and so the response to overfitting is triggered.

“Life can be boring at times,” he says in the study. “Dreams are there to keep you from becoming too fitted to the model of the world.”

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website