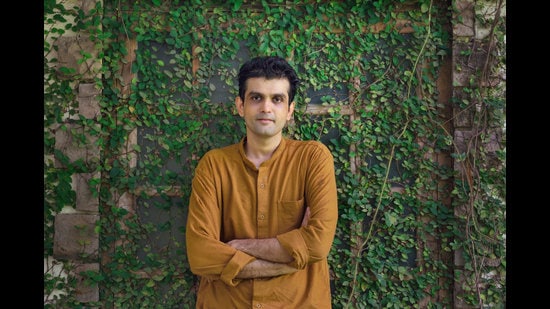

The real deal: Director Amit Masurkar’s journey from Newton to Sherni

How does one get a film to look so authentic? In Sherni, as in his last film Newton, the villagers are real, the forest officers actually do the job. It takes attention to detail, curiosity and a willingness to learn, says Masurkar.

He was 19, studying industrial engineering in Manipal, when Amit Masurkar fell in love with cinema. He watched Quentin Tarantino’s neo-noir black comedy Pulp Fiction 17 times that year (it’s a 1994 film, but still played almost on a loop in the video parlours that dotted the student town in Karnataka). “I didn’t understand it the first time. I wanted to understand what it was about the film that people liked so much,” Masurkar says.

So he found the script online, read it, re-watched the movie. With every viewing, more layers emerged. He moved on from Tarantino to Spike Lee, Werner Herzog and David Lynch, watching their movies in the same tiny video parlours.

For someone who hadn’t engaged with films much beyond the group family outing, these storytellers stirred something in him. So much so that he dropped out of engineering college, determined to make movies of his own. He started on a slight tangent, drawing cartoons for a youth magazine, then interned at MTV, assisted filmmaker Aanand L Rai on a telefilm, and wrote sketches for The Great Indian Comedy Show.

Through it all, he kept writing. Script after script collected in a pile (he still has the stack). Until Sulemani Keeda. The 2014 slacker comedy about two struggling writers trying to make it in Bollywood actually benefited from its shoestring budget. Most of the cast and crew worked on it just for the credits, and Masurkar called in favours to access shoot locations. But that meant that the struggle in the story was also the struggle of its making. The screenplay mined the inherent absurdities of an industry that demands hope as a kind of blood sacrifice, while usually offering nothing in return. All in all, the film exuded an authenticity that would become a Masurkar trademark.

Sulemani Keeda was enough of a slow-burn success to make raising money for his next film easier. But Newton (2017) would be more than Masurkar bargained for. It fared well at the box office and with critics. It shot Rajkummar Rao to fame, won a National Award and was India’s official entry to the Oscars. “There were a lot of expectations and I was a little overwhelmed,” Masurkar says, speaking from his home in Mumbai.

Now 40, his third directorial feature, Sherni, was released on Amazon Prime last week. Shot in the jungles of Madhya Pradesh, the film explores the fraught relationship between villagers living and farming on the edges of a forest, a tigress trying to make her way between shrinking habitats, and a forest officer (Vidya Balan) trying to keep the tigress and her two cubs from being shot.

Except for the quiet energy of Balan’s character Vidya Vincent, the innate lethargy of the system comes through in the gradual pace of the action. Election campaigning turns the tigress into a political pawn. Rather than combine forces to find her, the regional head of the forest division conducts a havan in the office, attended earnestly by the staff.

The screenplay by Aastha Tiku, as with the one by Mayank Tiwari for Newton, was the result of hours of extensive interviews with locals living in identical situations. “When you meet people and you talk to them, you find players you might miss when you’re sitting in Bombay and writing a script. So, it’s important for a writer to travel, meet people and read,” says Masurkar.

Sherni’s cast is a blend of A-list talent, veterans like Neeraj Kabi and Vijay Raaz, and real-life residents of villages near the forests where the film was shot. “Most of the forest guards, except for three or four actors, are real forest guards too,” Masurkar says. “All the villagers, except for Sampa Mandal, the NSD graduate who played Jyoti, were from local villages.”

On the surface, Sherni seems like a logical progression from Newton. Like the election officer played by Rao, Vincent is struggling to navigate a bureaucracy that doesn’t care about her passion or about the job being done right, so long as the paperwork remains unproblematic and the local bosses of all persuasions, unruffled.

But where Newton was fiery, uncompromising and quick to anger, Vincent has been mellowed by nine years on the job. She doesn’t fight because she knows she can’t win, but she doesn’t stop trying.

Masurkar sees his cinema as “being interested in big ideas and paying attention to small details”. After Newton, he knew his next story had to be particularly meaningful, layered, commentative. The climate crisis seemed like a good subject to tackle since it is also something that occupies his mind. “Everything is linked to the way we are treating nature — global warming, extinctions of species and to a certain extent even the pandemic,” he says.

“For the last few years, Aastha and I had been talking about doing something in the space of conservation. She started looking at various case studies involving rhinos, elephants, whales, tigers.” They finally chose the tiger as representative of the larger cause, the jungle itself.

As he tells his stories, creates his authentic worlds, the 19-year-old Masurkar is still in there, watching, questioning, learning. “These Malayalam new wave films are quite inspiring. I just watched Joji [starring Fahadh Faasil]. I really liked The Disciple [a Marathi film directed by Chaitanya Tamhane]. I watched [the 2019 film] Sound of Metal recently. I love Riz Ahmed.”

His next challenge will be a web series, working with Tiku again. “A storyteller must be curious.” Every film of his has taken on a different subject, so he ends up learning with each of them too, he says.

The conversation moves to Masurkar’s first time on a film set. “There was some shooting happening outside my school and it was recess so we stood around watching it. I don’t remember who was in it but I remember being really bored,” he says, “because they just kept repeating the same thing again and again.”

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website