Plot twist: How the bungalow was born in India, and has travelled the world since

All bungalows have their roots in colonial Bengal. See how they spread, how the style evolved. Tour the 21st-century inheritors of this tradition.

There are few words in the English language that can conjure as many vastly differing images as “bungalow”.

Depending on where in the world one is, and when, a bungalow could be a cottage-like structure amid a plantation in British Malaya (1826–1957) or a country home in rural England. It could stand for the official residence of a government administrator or evoke the ordered and manicured layouts of stereotypical suburbia.

The history of the bungalow is more than that of a private residence. It represents how the domestic space was transformed by factors as global as colonialism, industrialisation, urbanisation, and migration, and as local as personal desires, aspirations and changing traditions.

We’ll get to each of those in a bit. But the really interesting thing?

All bungalows have their roots in colonial India, where this housing format first emerged.

It took shape as a distinct architectural category in 18th-century British India, melding influences from rural Bengal with elements of rural British workers’ cottages of the time. The word “bungalow” itself is derived from “Bangla”, meaning “of or belonging to Bengal”.

This housing format draws its fundamental shape from rural huts that were common in Bengal at the time. Accounts written by European travellers such as Comte du Modave, Bishop Heber and Francis Buchanan, between the 17th and 19th centuries, describe a traditional Bengali bangla or a banggolo as either makeshift or permanent; made of bamboo, thatch, grass and mud; in the rough shape of a pavilion or a rural hut.

The roof could have two sloping sides, resembling an “overturned boat”, or four sides, extending over the walls of the structure and supported by bamboo or wood posts, to form a verandah. Extensions to the house could help it double as a place of work, such as a shop.

(There is more on this in the historian Anthony King’s fascinating book, The Bungalow: The Production of a Global Culture (1984).)

***

The colonial bungalow in India would retain several traits of the Bengali hut.

Typically made of mud and bricks, it was built on a raised platform, with a sloping roof made initially of thatch and later, tile. A pyramidal or four-sloped roof extended past the outer walls and was supported at the edges by pillars or columns, to form a verandah.

Inside, there were changes. The colonial bungalow was typically larger, meant to house a family and guests. It was laid out around a large hall meant for entertaining guests, dining, and sometimes dancing. Bedrooms flanked the hall, with dressing rooms and bathrooms towards the rear.

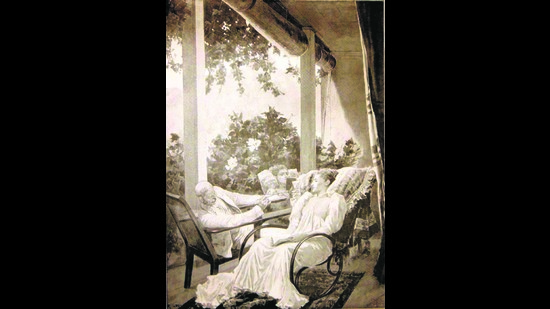

The verandah was a big part of the social life of this bungalow. It could be a place of repose or of business; it was ideal for entertaining guests. And it helped limit the access granted to outsiders.

In this way, the architecture of the bungalow demarcated public, semi-public and private spaces. In India, this would become useful when residents wished to segregate visitors and help based on factors such as race and caste. It would serve similar functions in colonial settlements across Asia and Africa.

***

Later variations in the architecture included flat roofs and high ceilings, modified verandahs and the incorporation of classical European architectural motifs and trends.

Soon enough, the more luxurious of these homes began to sit amid large lawns, lush with flowering plants and trees, adjoined by private tennis and croquet courts. Elaborate gatehouses were then added, and porticos large enough for an elephant to walk through, as well as stables and vegetable gardens.

From the mid-19th century, as the British Crown gained political control of India, institutions such as the public works department (PWD) and military board standardised the bungalow format in government-run enclaves, making it a distinct symbol of colonial architecture across Asian, African and Pacific colonies.

The business of Empire — whether administrative, military, commercial, leisure or infrastructure-related — resulted in forms such as the “planter’s bungalow”, “inspector’s bungalow”, and the trail of “dak” or “postal” bungalows which housed officials, travellers and, as Rudyard Kipling once wrote, “resident ghosts”.

***

As the British empire grew, subsuming local economies, the bungalow acquired an aura of “separateness” and desirability. In the segregated White Towns and Civil Lines areas of major colonial cities, each of these homes, situated in its own compound, with several placed evenly along wide, planned streets, represented the order, organisation — and exclusionary nature — of British rule, and underlined the stark contrast with the also-new but far-more-densely-settled “native” towns where the colonised now lived and worked.

Part of the prestige associated with the bungalow came from the small retinues attached to them, a lifestyle unthinkable for anyone but an aristocrat or royal, in the Western world.

There were cleaners, cooks, servers, gardeners, punkahwallahs who sat in the verandah tugging at swinging, roof-mounted cloth fans. There were ayahs for the children and housekeepers to help the lady of the house oversee it all.

By the turn of the 20th century, the bungalow was being adopted by affluent Indians.

By the 1920s, its popularity had trickled down to the urban middle-class.

As the architects and scholars Madhavi Desai, Miki Desai and Jon Lang observe in their book, The Bungalow in Twentieth-Century India (2012), this adoption reflected a fresh wave of change, driven by urbanisation.

As lakhs moved into the cities, there was a rapid suburbanisation.

An early middle-class was learning to live differently; not with people of the same community, caste or village, but in mixed neighbourhoods. The nuclear family was becoming more widespread too.

The bungalow, with the prestige and separation it promised, was an ideal way to signal status in this new setting. And so, across areas such as Bandra and Khar in Bombay, as well as in cities like Delhi and Bangalore, new planned layouts and housing clusters with bungalow plots began to emerge.

And so it was that the modern bungalow, rather than the haveli or wada for instance, became the default standalone housing format in cities ranging from Lutyens’ Delhi (built from the 1910s on) to planned industrial townships such as Jamshedpur (developed in the 1910s) and new state capitals such as Chandigarh (built in the 1950s).

***

Unlike the templatised PWD and military board structures, private bungalows became canvasses of their owners’ wealth and tastes, as well as of the architectural styles in vogue at the time.

Some would incorporate bold new elements from a burgeoning design school that made optimum use of mouldable concrete wall cladding: Art Deco.

Designs also accommodated prayer rooms, and traditions of gender-segregation.

In a big shift for the Indian family, the kitchen moved indoors — which was now possible because wood fires had been replaced, at least in the cities, by gas stoves. The kitchen platform made an appearance, and women began to cook standing up. Amenities such as refrigerators appeared; as did Western-style furniture (sofas, chairs and dining tables, crockery cupboards and sideboards).

Over the last few decades, the bungalow has become both a typology in danger of decline and a form of housing that sharply reinforces social and class divides.

It is disappearing, rapidly, from India’s densest cities (Mumbai, Bengaluru, even parts of Delhi and Hyderabad), hurt by rising land and maintenance costs, litigation between heirs, and simply the pressures of attempting to accommodate millions on a too-small patch of land.

Today’s status-symbol separations come not from a single family held within a boundary wall, but from a gated “enclave”, with its own swimming pools, spas, movie theatres, playgrounds, gardens, and 24x7 security. The truly wealthy still have bungalows; but they’re often farmhouses and villas on the outskirts.

The bungalows that remain stand out, just as they did when they first arrived, all those years ago.

(Rachna Shetty is a research specialist with MAP Academy, an online platform encouraging greater engagement with South Asia’s art and cultural histories)