Keeping it real: Shyam Benegal on retirement, change, his first film in 11 years

In conversation with Madhusree Ghosh, Benegal, now 86, discuss his India-Bangladesh collaboration, changing tech, new platforms for storytelling and more.

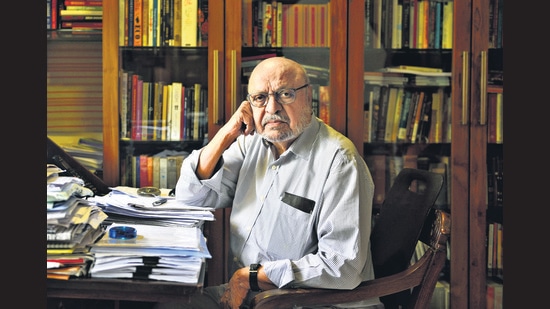

Shyam Benegal, 86, likes to joke that he’s always introduced as a man who needs no introduction, a line that is followed by a lengthy introduction nonetheless. It’s true, and unavoidable. So here goes: The filmmaker started his career 47 years ago with Ankur (1974), a story about a Dalit couple and their upper-caste landlord that was Shabana Azmi’s debut feature and is considered one of the finest works of Hindi cinema.

Audiences would come to recognise and love Benegal’s craft through subsequent films such as Nishant (1975) and Manthan (1976), stark tales, startlingly real, exquisitely lit, that followed everyday Indians as they struggled to be seen, heard, acknowledged.

His films shone a light on an India rarely, if ever, seen on screen. Mandi (1983), was the story of the residents of a Hyderabad brothel; Trikal (1985), of a Christian family in Goa during the last years of Portuguese rule. What made these movies impactful and evocative was that, beneath the quiet realism, were scathing takedowns of caste, class, disparity, India’s increasingly capitalist society.

These are the more public details of his work. What you may not know, as the long introduction continues to his dismay, is that the multi-award-winning Padmashri and Padma Bhushan continues to work out of the same small office in Mumbai that he has occupied for 44 years, answers his own landline, and readily sets aside time to talk about his craft.

He is currently shooting a Bengali film, Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal), a co-production by the governments of India and Bangladesh that tells the story of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, founding father of Bangladesh. The project has been planned to coincide with the centenary of Rahman’s birth (2020), and the 50th anniversary of the birth of Bangladesh (2021) and is due for release later this year.

This is Benegal’s first film in 11 years, since Well Done Abba, a political satire about a Muslim man trying to get his daughter married amid a rising drought crisis in his village. Why Bangabandhu? Is Benegal doing things differently? What does he make of the changes in storytelling, the new platforms, techniques and technology? Excerpts from an interview.

What was it about Bangabandhu that drew you to this project?

Mujibur Rahman’s life is like a Shakespearean tragedy, from a young leader and founder of East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League to a key figure in the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971, to becoming the first president, to the brutal assassination of him and his family (he was killed at his residence in 1975, along with his wife, three sons, two daughters-in-law, brother and nephew, during a military coup). The tale fascinated me. His was the kind of story that makes for high tragedy. Even the way his two daughters, Sheikh Hasina and Sheikh Rehana, escaped, because they were not in the country at the time.

His life story can be compared to a Shakespearian drama. He was passionate not only about Bengali as a language but about creating a Bengali nation. He gave his life for it.

It was a fascinating journey for me and my writers, Atul Tiwari and Shama Zaidi, to discover Mujibur Rahman from the various archives.

Are you doing anything differently, in this project? Do you think about movie-making differently, all these decades on?

When you are eating a meal every day, do you stop and think about the fact that you are eating? Movie-making is the same for me. I’m a filmmaker; this is what I do. When I started my career as a filmmaker almost 50 years ago, I used to think about how to be one. Now it’s like second nature. It’s like speaking a language or writing. It comes naturally. How well you can express yourself through the art of cinema, that’s a constant learning process. Every filmmaker wants to be more precise and lucid in his or her next film. I have to constantly hone my craft too.

What kinds of changes has that involved?

Technology has changed completely. I, as a filmmaker, have to learn the new technology as it comes, as these are one’s tools of expression. When we shot on celluloid, the kinds of exposure were adjusted manually. Now we don’t even need an exposure meter. It’s built-in, automatically giving you the right kind of exposure.

But what if one doesn’t want the standard exposure it gives? The advantage of advanced technology is that it stops you from making a mistake. But a filmmaker might still not get the result they want. To get the result the way you want it, with your individual view of the object, you have to go beyond the standard and do it manually. All artistic expression is subjective. We all have to go beyond the standard objective view the technology provides, to express our personal view of things.

Technological advances have changed ways of storytelling too. It allows you to express yourself in a more precise manner.

What’s next for you?

At my age you don’t think of what’s next; you do what best you can right at the moment. I’m trying to make the best of any opportunity that presents itself. I plan to work as long as I can. There’s no such thing as retirement. It doesn’t make any sense… Life will happen to you anyway. I enjoy life as long as I keep in good health and I plan to enjoy it for a long time to come.

.

New to Benegal’s work? Start here

Ankur (1974): Shyam Benegal’s debut feature, and the feature-film debut of Shabana Azmi (above). She plays a married Dalit woman who has an affair with the upper-caste son of a village zamindar. Subtle, evocative, rooted in the real, Ankur announced Benegal as one of the pioneers of the new-wave movement of the ’70s.

.

Manthan (1976): A crowdfunded film financed by 500,000 farmers who donated ₹2 each. Starring Girish Karnad, Smita Patil (above, centre), Naseeruddin Shah and Amrish Puri, it was inspired by the milk cooperative movement led by Verghese Kurien, which resulted in the foundation of Amul.

.

Bhumika (1977): Based on the Marathi memoir Sangtye Aika (You Ask, I Tell) of 1940s stage and screen actor Hansa Wadkar. This movie is a sort of foundation course in some of India’s finest filmmaking. Smita Patil plays the flamboyant artist struggling to define herself. The screenplay is co-written by Benegal and Girish Karnad, with cinematography by Govind Nihalani. Co-stars include Amol Palekar, Naseeruddin Shah and Amrish Puri.

.

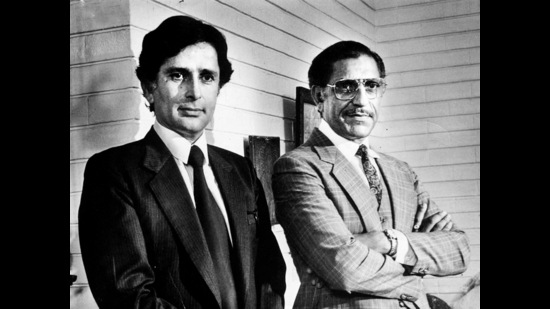

Kalyug (1981): Benegal got Shashi Kapoor to produce this retelling of the Mahabharata. Two industrial families, and cousins, compete for government contracts, affections, profit and power. There are layered performances by Kapoor, Rekha, Raj Babbar, Amrish Puri, Supriya Pathak and Anant Nag.

.

Mammo (1994): Farida Jalal plays a Muslim woman, Mammo, who becomes a Pakistani citizen after Partition but returns to India illegally, to her maternal home, after her husband dies. She is caught and sent back to Pakistan on a train. The film is poignant; Jalal is outstanding.