Digital art, NFTs and owning a tweet: India is getting virtually creative

NFTs are popping up at auctions, galleries, in music and film. Take a look at how they work, why they’re everywhere and see how Indians are creating and trading in them too.

They popped up overnight and suddenly they’re in everything. People are selling art and music as non-fungible tokens. Tweets, memes and films have sold as NFTs.

To recap, an NFT is a digital-only product — it might be a jpeg file, an audio clip, a GIF — bought using cryptocurrency (usually Ether, because most NFTs are based on the Ethereum blockchain, but platform such as Flow and Tezos use their own cryptocurrencies too).

NFTs, also called “crypto collectibles”, are essentially one-of-a-kind assets with unique identification codes that can’t be tampered with or duplicated. They’re stored and protected on a shared public exchange system called blockchain.

In a digital world defined by ease of duplication, this is what makes the NFT so desirable to some. It is designed to create a sense of scarcity. “With an NFT, you are assured of authenticity,” says Nischal Shetty, founder of the platform WazirX, which set up an NFT platform for Indian artists last month.

WHO’S MAKING THEM?

Anyone can create an NFT. Twitter co-founder Jack Dorsey sold his first tweet as an NFT. It reads “just setting up my twttr” and was bought by a Malaysia-based businessman for $2.9m (about ₹18 crore). Canadian singer Grimes, SpaceX founder Elon Musk’s girlfriend, sold a set of songs as an NFT, for $5.8 million (about ₹43 crore).

Art auction houses Christies and Sotheby’s have both held auctions of NFTs. Last month, Christies auctioned a digital composite of 5,000 pieces of art by Beeple for $69 million. Last week, Sotheby’s held its first NFT sale.

The American rock band Kings of Leon has generated over $2 million from the sale of limited-edition NFT versions of their eighth album, When You See Yourself, released on March 5. The different packages have included copies of the album on vinyl, album artwork and lifetime passes to future KoL events.

Trevor Hawkin released his feature film Lotawana as an NFT on March 17 and fellow indie filmmaker Kevin Smith will release his next movie, a horror film called Killroy Was Here, as an NFT too. As with Lotawana, Killroy Was Here will be auctioned to a single buyer. “Whoever buys it could choose to monetise it traditionally, or simply own a film that nobody ever sees but them,” Smith said in an interview with Deadline magazine.

NFTs IN INDIA

Digital artists in India are creating NFTs and raking it in. It’s becoming a rather crowded and competitive market, says Jaipur-based visual artist Pulkit Kudiwal, 20. You need to build connections as you go, stay active on the scene and liaise with collectors. “I try building connections on social media. It doesn’t always work out, but the key is to wait your turn,” Kudiwal says.

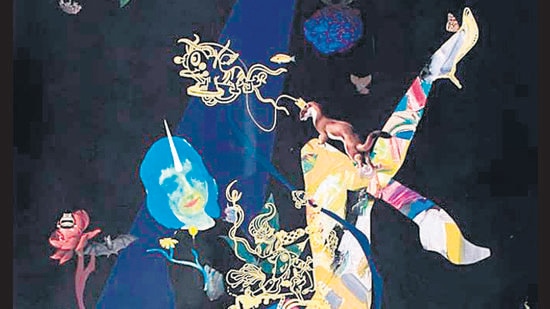

He has sold five digital creations on Foundation and Rarible, for a total of about ₹5 lakh. All his artworks feature surrealistic, post-apocalyptic imagery set in a fantasy world. Prasad Bhat, a Bengaluru-based illustrator, sold his first NFT — a caricature of Leonardo DiCaprio — for the equivalent of ₹2.82 lakh in March and has sold several caricatures of Hollywood stars since.

Siraj Hassan, a Chennai-based artist, has been selling works from a series titled Caged; music producer and 3D artist Ezzyland has been making audio-visual NFTs. Devan Suresh, a Kochi-based concept 3D artist and musician, has had two abstract digital drawings based on his everyday life sell for the equivalent of ₹2.60 lakh.

In February, when the French electronic music duo Daft Punk split up, Delhi-based 3D illustrator and art director Amrit Pal Singh created jpeg illustrations representing each member, tagged them as non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and auctioned them for the equivalent of ₹27 lakh. So far, Singh has sold five other such works, earning approximately ₹95 lakh.

Some of it is art in a new format, some of it is gimmick, some of it is people hitching their wagon to a fad.

“I’ve never been in the crypto economy to make a fast buck by trading. But I do think culture is a worthwhile investment,” says Bengaluru-based angel investor Nikhil Velpanur. He bought his first NFT on April 8 from artist Raghava KK, also a friend. “I’ve seen his artwork purchased by the big art collectors, I’ve seen them in highly acclaimed exhibitions, but could never afford it. I’m not an art collector, I’m just a random guy. But in the crypto world, things are different,” Velpanur says.

Each artwork was bought for about ₹85,000, which Velpanur considers a steal. “This will be worth 100 times more in the coming months,” he says. “A recognised, highly valued mainstream artist putting his artwork up on the chain as NFTs is some serious value.”

THE POLITICS OF NFTs

For some creators and buyers, trading in NFTs is a subversive way of getting back at a hyper-capitalist system that depends on centralised trade systems, ownership models and supply chains.

“By being able to prove provenance and giving creators the ability to trade and call the shots, NFTs are changing the game,” says Velpanur. “We are back to decentralisation — one doesn’t need curators, permission from the central tastemakers. It’s decentralised. It’s yours. The power is in your hands.”

There’s also the sense of history being made and archived. “With lot of memes and tweets that are being bought, the idea is that the collectors are paying for bits of internet history and digital history,” says Singh. “Somebody in 2040 will look back and be able to better understand what was happening in 2021.” A good example is a Nyan Cat meme from 2011 that sold for almost $600,000. These are bits of digital history that marked a point in the evolution of the internet, but will fade from public consciousness, except where they are preserved as art or memorabilia.

THE TRUE COST

There are growing concerns over the ecological cost of NFTs. It’s a format that is energy-ravenous. Units of cryptocurrency and transactions in blockchain are the result of a process called mining that involves computers guzzling energy as they conduct trillions of calculations to solve complex math puzzles in attempts to determine whether transactions are valid.

ArtStation, an online marketplace for digital artists, decided to cancel its plans to launch an NFT platform following backlash over how environmentally unethical this model is.

Joanie Lemercier, a French artist and climate activist, expressed horror when he discovered that six NFT videos he created a few months ago consumed in 10 seconds more electricity than his studio had over the past two years. He is putting future NFT releases on hold. “It felt like madness to even consider continuing that practice,” he said on his website.

HOW IT WORKS

A non-fungible token or NFT is an asset that exists only online, within the shared public exchange system called blockchain, as a one-of-a-kind product.

NFTs have been around since 2017, but have gained momentum this year, with many more being created and bought.

Anything can be an NFT – an image or art work in the form of a jpeg; an album in the form of an audio file; a film in the form of a video; even a tweet.

The only way to create, buy or sell an NFT is on an NFT platform, using cryptocurrency. The cost of uploading an NFT is known as a gas fee. Depending on the platform, the gas fee can range from ₹6,000 to ₹30,000, and it fluctuates depending on factors such as time of day and traffic on the network. Every time a work is resold, the artist is guaranteed royalties of 10% to 15%, depending on the terms of the platform.