Comic timing: Vir Das, Varun Grover and others on the role of the comedian today

What is it like to be dropping truth bombs in a time of distress? It’s hard, India’s stand-up comics say, especially in such a changed world. Hope keeps them going, and anger, and fear of the silence if they stop.

Joking is a bit like mining. You dig and shine your torch on what you find, but go too deep or place your dynamite wrong, and the whole structure becomes unstable.

The best jokes, of course, are timeless. But if you’re looking for the most current ones, the place to find them is at stand-up gigs, comedy clubs or late-night talk shows, on Zoom or at the local bar.

It is here that young urban Indians have, for about two decades, but increasingly over the past one, been talking about their families, their lives, their lies and their truth. It is here that we, in the audience, are confronted with the versions of our selves and our society that we know are down there, but that we don’t care to visit ourselves.

Take, for example, Niveditha Prakasam’s darkest joke from her spot in the 2020 Netflix stand-up special Ladies Up. She talks about wearing jeans in Coimbatore, Tamil Nadu, circa 2000. Jeans meant you were loose, she says. Guys would call out, “Hey, how much?” And, the joke goes, she’d respond with an incredulous: “You can’t afford it!” Her parents would get really worried: “What are you saying? You’re only 10 years old.” And to that she’d say: “That’s why they can’t afford it. Children are expensive.”

Now, there are those who will leap to the defence of Coimbatore, and those who will argue it’s not just Coimbatore (this is sadly true). But the point is not the city or the garment. It’s that with every twist, you, the listener, find yourself deeper in the mine. And it’s familiar and unsettling. You don’t want to flee, but you don’t want to stay too long either.

The thing about good stand-up is that it strikes a chord, and so it stays with you. Sometimes because you can’t forget about the fictional 10-year-old. Other times because it was just so purely funny that you want to revisit it for a private giggle. (Jay Leno talking about the first time he saw his name up in lights: “And it said JAY L NO. And I went to the guy and said, where’s the E. And the guy goes, ‘We’re out of Es. What can I tell you?’ And it goes back and forth and the guy finally snaps. “What… you think I can just go out and buy an E? I can’t just go out and buy a box of Es.” And that’s a stand-up master, riffing at the edge of the mine (he never did go very deep) but doing an unforgettable job.

Stand-up has kept soldiers going in war time, and revolutions going in peace. In the pandemic, it’s been a space for people to gather and, in a sense, commune. Vir Das in his At Home series invited audience members to talk about what they missed most, what they’d do first when things open up.

Comedians are talking about how hard it is to play this strange new role of joke-teller, grief support group and hope-giver. One recent virtual show ended up being more of a TED-style talk on grief, says stand-up comic Abhineet Mishra. It was so unlike his usual fare, he felt compelled to offer his audience the option of a refund at the end.

Mishra also speaks of having people in the audience who lost loved ones weeks earlier. “I thrive on mean jokes. But when someone thanks me for making them laugh because they lost someone... what do you come back with? What do you say to that?”

Indian stand-up comics have also been using their platforms to fund-raise, share information on the availability of hospital beds and oxygen cylinders. As they field desperate questions and try to keep their families safe and their own heads in order, the jokes can get shoved to the sidelines. Or they can become darker, more ravaging and rage-fuelled.

So where is the line for them? How do they see the comedian’s role today, and how far do they feel they can push it with riffs on death, sickness and apathy in a time of so much suffering? In one of his virtual shows on death and grief, Das tells the audience: “My job as a comedian is to talk about the elephant in the room. And I am not going to not do my job because the elephant is a dead body.” The role remains the same as it’s always been, adds writer and comedian Varun Grover. “To make people laugh while giving a unique take on things we all have experienced.”

.

LAUGHING AT A FUNERAL: VIR DAS

Vir Das says the pandemic has been freeing in many ways. His material has acquired more depth, a sort of cathartic quality. It’s far more personal and rooted in empathy. Despite the glitchy connections and the strangeness of doing stand-up in an empty room, he says he’s had the most creative two years.

In addition to his many virtual shows, in 2020 he also raised ₹37 lakh for charity through a special series of 30 virtual shows shot at his Mumbai residence. A month later those shows were turned into a Netflix special, Vir Das: Outside In. When the second wave hit, he launched the Vir Das At Home series to raise funds again for Covid relief.

His ongoing Ten On Ten series on YouTube (10 shows, each addressing a different aspect of the times we live in) has gathered around 5 million combined views. These shows, where he sits sometimes dejected and under-dressed, act as hyper-realistic portraits of the present as it unfolds. He discusses death and the failures of the system, religion, humanity, and how we are losing our voice, in so many ways.

On how the pandemic has altered his comedy

I’ve been in the business for 13 years, so there’s a certain amount of luxury. You fly in a nice plane and stay in a nice hotel and if you like a certain kind of biscuit those biscuits are waiting for you. Suddenly, with the pandemic, you’re carrying your own speaker up a hill and setting it up and performing for 50 people. I think you start to approach your material with a nothing-to-lose quality. I can kind of talk about anything because what’s the worst that can happen? 50 people will go home? That’s where the Ten On Ten came from. I thought, if I’m going to do it, I might as well keep it authentic. Even before the pandemic, I was always thinking, what did I do last and can I do the opposite of that? That’s really how I run my career.

On the role of the comedian in times of distress

The role is to make you laugh. The problem is that people are imposing too many other roles on us. We’re not your politicians, we’re not your journalists. We’re supposed to make you laugh by talking about those other people. Yet I acknowledge that if I’m privileged enough to continue doing his job during the ongoing Covid-19 crisis, I must weaponise this platform for something greater.

The biggest loss and biggest learning

The workout room has been the biggest loss my artform has suffered. Usually I’m just writing 10 minutes of jokes. But for online zoom shows, I’m writing 30 to 40 minutes of new material and have no place to work them out. The first time I did these Vir Das At Home shows, I performed in front of 1,000 distant faces, which is a weird way to do stand-up.

People value authenticity and that’s the learning in the last two years for me. It doesn’t matter where you’re from or what your format is. It all comes down to, are you authentic? I think this new generation can smell a bullshitter a mile away. You’ve got to be real.

A joke that pushed the envelope

I think Ten On Ten pushed the envelope quite a bit. I think there’s a section there about desperation, where I kind of knew that it wasn’t funny, but all the other dark material would not work if I didn’t address how desperate people had got or how crushing that experience can be, so that was something I was happy I said.

The lines go, “I know so many of us feel broken right now because you rushed from hospital... to hospital and you couldn’t find oxygen... But always remember that the ones you lost, saw you try... You screaming at a security guard... You reading a sign in disbelief... Desperation is nothing but unconditional love in its purest form.”

I think as you get older whatever is inside you comes out more easily. I had lost people to Covid; many of my friends did too. So this pent-up feeling just emerged. It’s akin to laughing at a funeral, which I’ve done many times, and many people have done many many times.

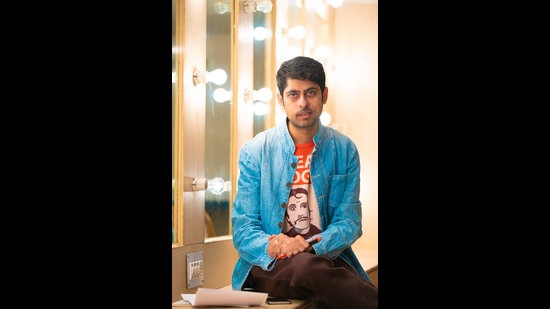

50% HOPE, 50% FEAR: VARUN GROVER

The role of the comedian doesn’t change, says Varun Grover, 41. It is to make people laugh while offering a unique take on things we have all experienced. But in the pandemic, he’s had less time and mind-space for comedy and no easy way to perform it, he adds.

Grover is based in Mumbai and wears many hats. He’s a screenwriter (Masaan, Sacred Games), a National Award-winning lyricist (he worked on Gangs of Wasseypur, Dum Laga Ke Haisha, Udta Punjab), a short story writer and a stand-up comedian. He’s one third of the political satire show Aisi Taisi Democracy (with Rahul Ram and Sanjay Rajoura).

“It’s difficult to say what will emerge from this time, but one great example is Bo Burnham’s Inside on Netflix. He wrote and shot the 90-minute show alone, in his house, and comments on a range of issues we have all faced during this time. So I believe comedy will bring new perspectives on how to deal with tragedy and lockdowns.”

On the biggest loss to his art form

The joy of performing for a thousand people in a closed auditorium, all laughing and carefree and maskless and believing in a world that is free. I am afraid we might not see that level of ignorance ever again.

A subject he won’t joke about

I have done it in the past and am ashamed of it, but for the last few years and definitely in future, I won’t make jokes about people with less social privilege than me in terms of caste, class or gender.

On what he hopes to give his audience

Other than a laugh, some new insight, a little fracture in their prejudice, and sometimes just better general knowledge. My target audience is myself. If I find it funny, I believe there are enough people like me who will find it funny.

On why satire

I chose it because I grew up in Uttar Pradesh. To survive there, you either need political power or a sense of satirical humour. The three things I find myself joking about most often are lack of scientific temperament, moral policing and political jumlebaazi. On good days, my comedy is fuelled 100% by hope. On bad days, it’s 50% hope and 50% fear. But the hope never goes below the 50% mark.

.

TURNING THE TABLES: MERENLA IMSONG

Merenla Imsong, from Kohima in Nagaland, wrote a savage song in March 2020. It’s about the pandemic, but also about a problem that predates it: racism and prejudice against north-east Indians. Playing the piano and speaking of someone who called her cousin Corona, she sings, in one part: “I’m sorry that you’re a parody of the human gene pool.”

Imsong’s first take on the issue was the famously light-hearted, based on the idea: What if people from the north-east asked the kinds of questions they are typically asked? Titled Presumptuous Chinky Assumes the North Indian Way, it was uploaded on YouTube four years ago and quickly went viral. “I have a friend from the north-west. Her name is Pinky Singh,” she says, facing the camera. “Do you know her… Pinky Singh!?” There’s also a bit where she struggles to match capitals to states, expresses surprise that Bihar is not in UP, and tussles with the name Moo-kesh Kejj-raaai-wall, looks at the camera and smiles kindly. “I’ll just call you Moo.”

“For me, comedy has always been a space to relax and unwind, and laughter is now even more important,” says Imsong. Stuck in her tiny rented flat in Mumbai, making funny videos became a coping mechanism. Now back in Nagaland, she simply wants to laugh and to make others laugh, she says. As for the song, she wrote it after reading reports of a man in Delhi spitting on a Manipuri girl and calling her “Corona”. Sometimes the frustration and disgust just bubble over, she says.

On how the pandemic has altered her material

I’ve learnt to make content from lived experiences and not just hashtags and trends. The way people tend to outrage on social media is very polarised and anger is the easiest emotion you can latch on to. I can’t be posting random Instagram stories. I’d rather just sit by myself and examine what is causing the anger, think logically, and avoid the trap of feeling like a victim. Do a little digging: that is one responsibility we have.

On the kinds of content that will emerge from this time

I think a lot of people are talking about mental illness now, because everyone is going through collective gloom. So we’re more comfortable talking it about, laughing about it. Comedian Daniel Fernandes did a whole set on it recently.

A joke that pushed the envelope

I posted a video titled How to Nail an Election in Nagaland on YouTube two years ago. It’s advice for aspiring politicians. “In order to know your voters, it is important for aspiring politicians to understand what the voters would prefer as bribes — money, alcohol, promises.” That kind of thing.

On trolling and women comedians

When you’re female, you just get reduced to a piece of meat. So it’s just general comments about your body and your looks and not much to do with your content. It’s getting boring. To be honest, I’m disappointed at the level of trolling I get. I thought up better insults when I was seven.

.

BREATHING UNEASY: ABHINEET MISHRA

Performing after the lockdown was lifted, in Guwahati and Mumbai in February, the masked audience was unsettling for reasons Abhineet Mishra hadn’t anticipated. There was the sound of laughter, but no sight of it, he says. “And seeing audience members masked kept reminding me the pandemic was out there, the grief. It is so difficult to lift people up in this situation.”

Mishra, 34, is a former journalist and a native of Shillong. He’s performed across the country. But as a comedian, he says, the person telling the jokes is also going through their own little journey. And in this past year, no one has escaped untouched.

On the role of comedy in times of distress

The comedian is even more critical at such a time. Stand-up comedy has this element of standing up to the establishment. I think that element is emerging more strongly now, because almost everyone agrees that this is a colossal mess. A comedian can channel some of the anger into the comedy they create.

Personally, I wouldn’t joke about a person’s failing lungs. But I did. I wrote a joke calling lungs anti-national. It’s important to hold those in power accountable and stand-up comedy has a role to play in that. The filmstars won’t do it, the people with power won’t do it. I think there will be more content built around the devastation we’ve seen. In what form? We don’t know yet. But the pandemic has certainly defined a generation.

On what’s off-limits, as far as comedy goes

Drawing the line has been difficult in this time. What’s off limits to me is belittling people for their beliefs. Orthodoxy cannot be solved by humour. It will take more than a one-hour stand-up comedy show. On the other hand I feel, now is not the time to devolve into a political argument for no constructive reason. Or even polarise a joke, I mean there has to be space created for conversation, a middle ground that perhaps art can help create.

We cannot get through the pandemic if we keep moving in silos and dividing ourselves. We are all struggling. My best friend was in the ICU for weeks. A Zoom show around that time turned into a TED-type talk. We were in the midst of the second wave. Seven people had to cancel because they were going through some kind of sickness or loss. The last ten minutes was just a reflection on that, and people began sharing their own stories. So it went from being a comedy show to something else altogether. In the end, I asked my audience, in all seriousness, if they would like a refund.

But back to the idea of using someone else’s personal beliefs as a punchline, I feel there is a problem of narcissism in comedy today. Too many comedians think their opinion is the only valid one. You don’t want to become the extremist you’re trying to challenge.

A joke that pushed the envelope

Last year, after the Assam floods, we did shows around it to raise funds for relief. One joke went: “When an India-New Zealand match gets washed out, you guys go, “What the f**k. But when the north-east gets washed out, you guys go, Who the f**k?”

The region needs representation. So I will do my bit. Also, when I’m doing a set, I want to find at least 15 minutes in the hour to talk about a social issue. I do comedy to enjoy myself. I still want to be a light-hearted guy at the end of a show. But I’m also writing for myself. Because at least 30% of the audience will not like you, not like your joke.

.

NO KIDDING: PRASHASTI SINGH

For Prashasti Singh, 34, the pandemic has been a time to step back, think and find her true voice. Singh’s usual style so far has been to weave together anecdotes and observations about life in small-town India. In the Netflix special Ladies Up, she riffs on the TV journalist Ravish Kumar, real-estate and her home state of Uttar Pradesh. “Despite the fact that he’s a senior journalist, he still goes on field, in search of new stories in these villages. Now I understand why... in his youth he must have made the same mistake as me and invested in a real-estate property between Darbhanga and Patna.”

Much of her comedy draws on her lived experience. The jokes are unique but relatable. As with so many, her reality has changed since March 2020. In April, she was among the tens of thousands struggling to find a hospital bed and oxygen supply, in her case for her 60-year-old mother. “I’m just using this time to be more academic about writing and comedy. To think about how I feel as a citizen of this country and as a human being on Earth,” she says. “There’s definitely a change in approach to thinking and writing, happening within me.”

On the role of the comedian in times of distress

It’s up to every comedian what role they want to play at a time like this or if they want to play any role at all. Comedy can be a much-needed break from all the distress. But it has to be empathetic. It cannot discount the fact that people are suffering. It has to either address that people are suffering or be part of the healing in some way. A secondary goal, for me, is to bridge the polarised gap, to make somebody with an opposite view laugh.

On what’s off-limits, as far as comedy goes

A comedian should be able to joke about anything, in an equal, ideal society. But of course out in the real world, there are people who are powerful, who are oppressors. Whenever you’re making a joke you’re always punching up or punching down. My line typically is that you should not be punching down. One’s jokes should not be at the cost of a person or a section of society that is oppressed and will suffer more as a consequence of a culture of comedy.

A lesson learnt in the pandemic

That there is an audience for everybody. Different styles of comedy and comedians can exist and a lot of different types will tune in to watch. I’ve also learnt that one has to adapt to survive. An art form should not be dependent on the medium; it should navigate across media. I’ve also learnt that it’s totally all right to not make jokes, to mourn rather than try to be relevant.

.

THE TWISTER: NIVEDITHA PRAKASAM

The pandemic has changed her as a person, says Niveditha Prakasam of Coimbatore. It’s been a year since she did any live comedy, though, so she’s not even sure how much she’s changed, she adds.

“As comedians, we’re struggling through this. Unless you’re famous or rich, it’s hard to even continue doing the job right now,” she says. “So if you’re lucky enough to still be here then it’s like, congratulations you get to do this awesome and fun thing that pays sometimes.”

Prakasam shines in the 2020 Netflix stand-up special Ladies Up, where she touches upon colourism and why Tamil movies don’t do their community any favours. Her following she guesses is an English-speaking or urban audience. And south Indian girls. “It’s a very small and polite audience. I haven’t faced the kind of hate my peers face,” she says.

On lessons and losses from this time

My job was live stand-up. To get with the times, I did Zoom shows, but they just weren’t for me. I decided to give it all up for a while. But I’m slowly trying to put myself out there again. It’s quite daunting, to be honest. Especially internet content. It’s a whole other art form. So this period has taught me patience.

The pandemic has forced a lot of budding, talented comics to quit. It has also made it harder for there to be diversity because the more marginalised you are, the harder it is to sustain. To me, that’s a huge collective loss.

On the role of comedy times of distress

Comedy makes people forget. I think tragedy brings out the funny in all of us because there isn’t another way to survive it.

A joke that pushed the envelope

I did a bit on the stigma around dark skin in my Netflix special. The closing joke was: “This guy came up to me one time and said, “You are so dark!” and I said, “So are you... Dad!” I told it because I want people to start this conversation that gets pushed under the rug so often. It’s 2021 and Indian cinema still continues to brownface. It’s disgraceful to the people of this country. And our film industry should be embarrassed about it.

Rage fuels my comedy. There are so many things to be angry about and how better to navigate this emotion than to turn it into a joke. The satire and sarcasm… come from being fed up with a lot of things.

What she hopes her audience walks away with

Some perspective. There are hardly any Tamil women in entertainment. It’s sad but we have no representation. And so people have no idea about us or our opinions.

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website