A giant shadow: Mridula Ramesh writes on elephants, climate and India

They have no sweat glands, and so the story of the elephant is the story of water. They never forget, and so they follow paths that no longer really exist. We love and revere them; capture and worship them. In this month’s Trade-Offs, an overview of India’s friendly giant.

It was sunset, and she was smiling as she applied an ungodly shade of purple to a statue that would become the cynosure of all eyes in some street, come Vinayaka Chaturthi.

In the Hindu pantheon, there are few deities with wider appeal than Ganesha. He is considered brave, clever, witty and capable of overcoming any obstacle. Culture imbues elephants with the same qualities: a noble temperament underpinned with strength, and an unforgiving memory. Even a pope was a fan. Hanno, the pet white pachyderm of Pope Leo X (1475-1521), entranced Romans centuries ago. When Hanno died (supposedly due to a gold-laced laxative), the pope wept and wrote the elephant’s epitaph himself.

Chanakya’s Arthashastra says that a good king earmarks entire forests for them, since the strength of an elephant army (which acted like a formation of tanks, in ancient warfare) dictates war outcomes.

The Mughals used elephants in war, to charge and break enemy ranks, and in peace, to buttress the imperial image. Akbar is depicted taming elephants in musth (when serum testosterone levels reach 60 to 140 times the non-musth normal) to underline his masculinity. Jahangir reportedly had 40,000 captive elephants — far more than India has in the wild today.

In 1877, then-Viceroy Edward Robert Lytton rode an elephant in his infamous Delhi Durbar, to appropriate the Mughal image, even as millions starved in a great famine. Sixteen years later, Bal Gangadhar Tilak co-opted the elephant-headed Ganesha into the freedom struggle, by making Chaturthi a community celebration.

***

There’s something about elephants. Despite being the largest land animals, they are curiously gentle. Are they intelligent? They navigate complex social hierarchies that see females lead herds of more than 100 members.

They are highly protective of their young: on a visit to the Nagarhole tiger reserve in Karnataka, I saw a newborn in the midst of a herd. Within seconds, the mother and two females surrounded the baby, leaving only the faintest memory of a sighting. Later, my husband and I observed a family crossing a large lake. Over half an hour, the baby was buoyed by multiple trunks and carried securely over the water, even as boisterous younglings splashed some distance away.

Young elephants can be naughty and charming in equal measure. Also in Nagarhole, we met two calves named Apoorva and Airavata. Apoorva clung to her mother, who carried us sedately. Airavata hung back and then charged, gathering momentum to add bite to his infantile tusk as he rammed into poor Apoorva, who would wail in pain and nuzzle further into her mother. Another female tried to hold Airavata back, but to little avail.

Elephants appear to self-medicate. At the tail end of a pregnancy, which typically lasts 22 months, African elephants chew on the leaves of the Boraginaceae plant to induce labour; Kenyan women brew a tea from this plant for the same purpose.

Elephants tap expertly into hidden underground sources of water. They use tools, of a sort: branchlets become fly-swatters, branches are used to knock over a solar fence.

While experimental evidence on captive elephants’ intelligence is equivocal, field researchers are united in praise of the animal’s intelligence. Raman Sukumar, a renowned elephant expert and vice-chairman of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), told me, “There are different categories of intelligence, but what amazes me is how elephants think their way through problems and issues they encounter… they do have a superior intelligence.”

They are subtle too. When they encounter an elephant skeleton, they caress the bones, running the tips of their trunks over the nooks and crannies, much as we might mourn at a grave.

***

Awe-inspiring, naughty, clever and subtle. Should they have rights?

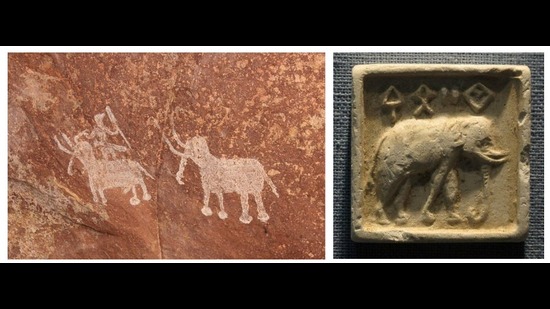

Elephants have been ceding ground steadily to humans. The Bhimbetka caves, an hour from Bhopal, contain some of India’s best cave art, some of it stretching deep into prehistory. Elephants appear in them 61 times. The area has no elephants now.

When elephants went extinct in Ancient Egypt, the pharaohs began to hunt them in the Tigris-Euphrates basin, where they also died out.

Ancient writings such as the Gajashastra, a manual on elephants dated to the 5th century BCE, show that they lived in the forests of the Indo-Gangetic Plain; both elephants and forests are gone from here now.

One recent study shows that habitat suitable for elephants has shrunk by two-thirds since the subcontinent was colonised. Their numbers appear to have rebounded from the lows of the 1980s, after the launch of Project Elephant, but a recent drop in Kerala (from about 6,000 in 2017 to about 1,700 in 2024) is concerning. Sukumar however advises caution when extrapolating inferences from the census because drought-related deaths, capture on a large scale, and poaching, the usual culprits behind falling populations, do not appear to be at play here, he says.

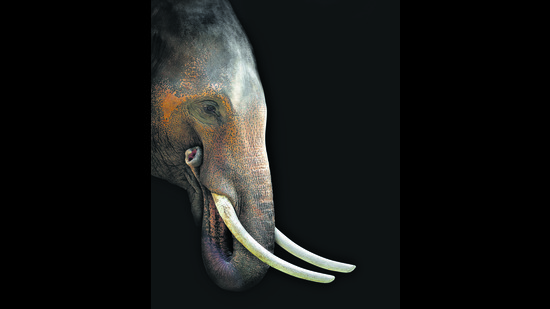

Human-elephant conflict is at an all-time high, killing 600 humans and 100 elephants annually. To understand why, consider the elephant’s beginnings. Their paleo-progenitor likely originated near the Tethys Sea, in the present-day Himalaya. Their closest extant relative is the sea cow.

This aquatic past has consequences. Elephants lack exquisite neuroendocrine control over water loss since they lack sweat glands save between their toes. Desert ungulates, for example, conserve water by controlling how much they sweat when water is scarce. Elephants cannot do that. So, when it gets hot and other ways of releasing heat (bathing, covering themselves in mud, flapping their ears, etc) prove insufficient, they lose buckets of water via their skin.

That’s what a study tracking skin temperature and water loss of captive elephants found: in the trade-off between losing heat and losing water, the elephants prioritise losing heat, and so risk dehydration without adequate water and shade.

An elephant drinks 150 to 200 litres of water and eats 150 kg of feed a day. Multiply that by the size of a herd, in the context of splintering forests and disappearing grassland across India, and one begins to see the problem.

Perhaps this is why elephants move so much. They need shade in the day. In the dry season, they seek out waterholes, while in the autumn and winter, they prefer open spaces such as grasslands. The latter coincides with harvest time, which is why human-elephant conflict peaks in winter.

Moving with the seasons along historic routes, they cannot be neatly confined within protected areas. To make matters worse, elephants are moving to the rhythm of their favoured foods. A forest guard in the Palani hills says that come jackfruit harvest season, elephants arrive. One young bull, he said, would show up like clockwork as the potatoes ripened. He was shy, needing only a torch shined in his direction to duck behind a nearby tree, face hidden but body completely visible, waiting for the humans to go away so he could get at his beloved potatoes.

As elephants become crop-raiders, they invite a backlash.

***

Other times, migration is forced. According to Sukumar, elephants are moving to Chhattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh (MP) from Odisha and Jharkhand, where mines have splintered their homes and unfavourable climate may have triggered their dispersal.

On a visit to Bandhavgarh National Park in MP a few years ago, we were told that four tiger cubs had gone missing, in the chaos unleashed by the entry of an elephant herd into the Tala region. This was the first time elephants had ventured here in living memory, our guide added. Today, reports state that Tala is home to 50 pachyderms.

There is also the problem of invasive plants. Elephants don’t eat the lantana, which has invaded large tracts of Indian forests, where it outcompetes native edible undergrowth. With less feed inside forests, elephants venture into fields.

The converse can be true: the removal of invasives heralds the return of elephants. In the Berijam range of the Kodaikanal hills, the forest department cleared 250 hectares of wattles and planted a variety of grasses on the land. Soon, a herd of elephants began to return.

The loss of grasslands across India poses a threat. These were viewed as valueless by the British, who couldn’t see past the timber, and grasslands gave way to plantations and fields. Elephants, as grazers and browsers, suffered. When field supplants grass, what do elephants do?

They move through them, munching and inviting conflict.

India’s cultural respect for the elephant has kept retaliation somewhat in check. One study in North Bengal, based on interviews with more than 100 farmers, found that many in the Hindu and Adivasi communities regarded the elephant as sacred and were thus reluctant to even demand compensation when it damaged their crops.

As one respondent put it, “The elephant is not at fault. It comes to fill its stomach as the forests have become empty.” This attitude appears to hold across large parts of India. Six humans die for every pachyderm killed in human-elephant conflict in India, while in neighbouring Sri Lanka, three elephants die for every human.

Myanmar’s elephants are being poached not just for their ivory but also for their meat and skin. Poaching numbers in India remain low, but, make no mistake, when we become complacent, there are many waiting in the wings to slaughter elephants for ivory.

But… tolerance has its limits. Repeated depredation of fields leads to misery on both sides. Remember the image of an elephant with its trunk blown away by a hidden country bomb, standing in a river, in pain, waiting to die?

What to do? We can begin by understanding why elephant’s move, respecting corridors and then working with local communities to protect fields, pay adequate compensation for crop damage, and rid our forests of invasives.

One company earns carbon credit by clearing hectares of Prosopis to make biochar. This approach can be applied elsewhere. Moreover, fragmented forests are more vulnerable to climate change, and grasslands are better than invasive-filled forests for downstream (summer) river flow.

The story of elephants is the story of India’s seasonal waters and how climate change and splintering, weakened forests are leaving us both vulnerable.

Maybe, by helping the elephant we help ourselves.

(Mridula Ramesh is a climate-tech investor and author of The Climate Solution and Watershed. She can be reached on tradeoffs@climaction.net)