The partition of hope for Telangana

Telangana has become the 29th state of India. But it has opened the floodgates of old hurts and anxieties, souring the present. HT talks to a cross section of people on the birth pangs of the new state as they grapple with the changed realities.

This June, every Hyderabadi has two or three of these novels running in his head. One is a Ghetto Novel in which upper-caste Andhraites feel that their story will unfold, like the rich but persecuted Jews, in a resurgent middle caste-dominated Telangana. The second is a Partition Novel in which some people feel others want to push them back to their place of origin. The third is the Soviet Novel in which the Telangana chief minister K Chandrasekhar Rao (KCR) is being imagined as a ‘Commie punk’ who will separate the Andhra rich from their money and redistribute it among farmers and tribals.

The truth is somewhere in between. What these anxieties reveal, say experts, is the way the middle class experienced the different phases of the militant Telangana movement and their fear that KCR, (under the pressure of being the leader of a non-violent statehood movement in a state with a long history of armed struggle) will be forced to repay his debt to this interconnected legacy. So far, Andhraites have controlled the state’s political and economic power. Under a Telangana establishment whose leaders continue to talk of a ‘local-non-local’ criterion from various platforms without clarifying the fields in which they will be applied, they wonder if they are actually being asked to leave.

This summer, bureaucrats will be at the mercy of bureaucratese and it is the top officers who will feel the bifurcation pain most of all. What is at stake is a power struggle — who should govern Telangana, not about who should stay there. In a telephone conversation from Vijaywada, IYR Krishna Rao, chief secretary, Andhra Pradesh, says a committee “has been set up to decide guidelines for allocation of officers and heads of administrative departments. Lower-level staff stay where they are.”

In an office at the end of a corridor in the still-common secretariat of the two states in Hyderabad, bureaucrat Madhusudhan Vedula of Telangana also busts two newspaper headlines in one go. The furniture may be shifting around, master files may now have to be duplicated, but the difficulties of state bifurcation is being overcome at individual levels, with grace. In his hand is a file of a list of travel agents who can, if his proposal passes with his superiors, bring business to both states. “Why re-invent the wheel? The two states should work together,” he says, as one of his personal assistants, who had declared himself “complete, authentic, total Telangana” a while ago as Vedula had left the room for a meeting, shrinks back in alarm.

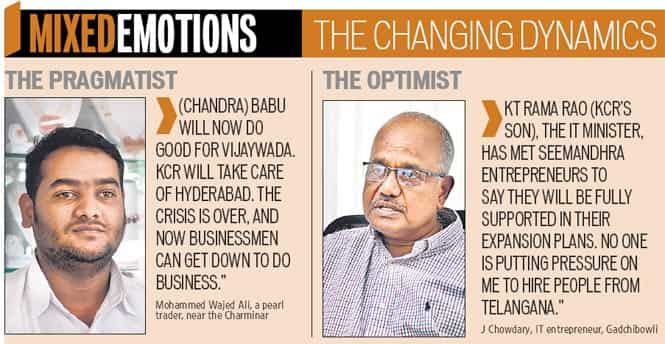

Telangana’s streets are less angsty about the split, though. After experiencing a cycle of militant struggle, which would erupt every 10 years since the first one broke out in 1944-48, Telangana has become India’s 29th state, and now they want it all to stop. Mohammed Wajed Ali, a pearl trader who runs a shop near the Charminar, says with a smile: “(Chandra) Babu will now do good for Vijaywada. KCR will take care of Hyderabad. The crisis is over, and now businessmen have to do business.”

Can the same be expected of the two Telugu-speaking people staying in Hyderabad, separate dialects be damned? For that to happen, their common history of success and backwardness has to be acknowledged to realise what actually brought them to this point. Telangana’s recent triumphalism, say its people, is a backlash of 60 years of economic and cultural suppression by Andhraites, which the latter say, has been brought on by 60 years of Telangana’s own inertia. For every Andhra person who thinks a person from Telangana is one who is “ever ready to pee to shirk work, and is waiting for a free lunch”, there are as many people from Telangana who feel every Andhra person is “bullish, part of an exploiter class who have made it big only because of caste and kinship links”.

Not all of the charges are untrue. Many Andhraites, such as cinematographer Shiva, empathetic to the latter narrative, point out how Telugu films, for instance, dominated by coastal Andhras, invariably have “villains speaking in the Telangana dialect. The people of Telangana have always been made to feel they are less”.

The problem with stereotypes is that if they are ‘good’ — i.e. if they can be backed with evidence — they stick and they wound indiscriminately. City geographer Anant Maringanti, born and bred in Hyderabad, says his father, a college teacher from coastal Andhra, who lived and worked in Hyderabad since the 50s, began to feel unwelcome ever since the movement for a separate state entered its final phase. “He was attached to Hyderabad and also to the place where he came from. ‘Everyone born in Lanka has to be Ravan is it?’, he would ask, only to be told that they were saying that about some other people, not him….”

Hyderabad blues

In 10 years, Hyderabad will be the exclusive capital of the state of Telangana. Its cosmopolitanism predates the IT-isation of the city. It has been home to Turks, Marathas, Gujratis, Bengalis. “There may be stray incidents or election rhetoric, but if no one is asking people of other states to leave, no one is asking Andhraites to go,” says professor Padmaja Shaw, Osmania University, one of the headquarters, so to speak, of the statehood movement. “If Hyderabad was so fundamentalist, this assembly election, the Telangana Rastra Samiti (TRS) should have swept Hyderabad. Only a few of its candidates won,” says Professor G Hargopal, University of Hyderabad, a well-known civil society activist.

The blues and the paranoia surrounding the split may be mainly about the loss of Hyderabad, the former revenue engine and capital of Andhra Pradesh, but there are reasons for the sharpness of rhetoric on either side. “What some Andhraites fear more is losing their dominance, with time, they will get used to feeling equal,” adds Hargopal.

On the city’s thoroughfares, the hoardings of the new political class indicate that the nexus of upper-caste and economically-dominant communities may be cracking. Rauf, a taxi-driver, pointing to a hoarding of KCR and other TRS leaders, says: “One of his deputy chief ministers is a Dalit and the other a Muslim. How many chief ministers have like KCR, handled the OBC, minorities welfare portfolio? Usually that’s a punishment portfolio or given to a low-rung minister. Surely that must mean something!”

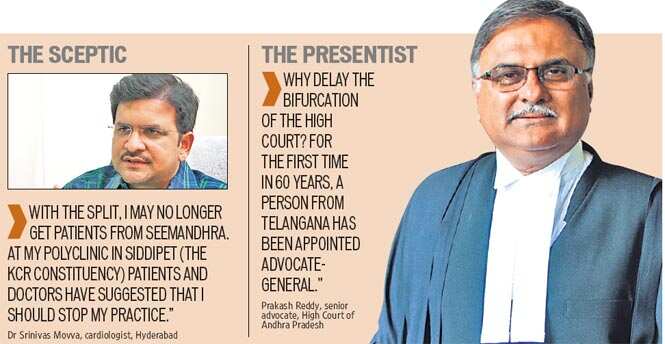

The city’s professionals are coming to terms with the new reality called KCR in different ways. In air-conditioned offices, he is the elephant in the room. Everyone is careful to speak if not well of him, then certainly, no ill of him. For cardiologist Srinivas Movva, who runs a Hyderabad-based hospital with wife Madhuri Movva, a gynaecologist, the new government, he feels, should do more to reassure Andhraites that their livelihoods will not suffer. “At my polyclinic in Siddipet (the KCR constituency) patients and doctors have suggested I should stop my practice.” J Chowdary, co-founder of Talentsprint, an innovation start-up that trains professionals in the IT sector, says, on his part, he has experienced no strong-arm tactics by TRS cadres. “KT Rama Rao (KCR’s son), the IT minister, has, in fact, met Seemandhra entrepreneurs to say they will be fully supported in their expansion plans. As far as hiring goes, people are hired according to what they bring to the table. So, there’s no question of getting directives for hiring people from Telangana or Timbuktu.”

Those who still take the critical vein, ironically enough, are KCR’s old comrades. Trade unionist Pradeep Burgula clarifies that for the KCR government, their support comes with strings. “We were part of the Joint Action Committee together. For us, Telangana, was about giving people the confidence to struggle. Now there will be other demands,” he says. “Polavaram (dam), farmers’ loan waivers, land to Dalits…. KCR has promises to keep.” This story is clearly not over yet.