The making of Mamata Banerjee

From a rabble rouser to a game changer on whom 90 million people pin their hopes for a new tomorrow, Mamata Banerjee has come a long way. Rajesh Mahapatra and Ravik Bhattacharya decode the making of Bengal’s new leader. The Mamata machine

On May 13, when Bengal counts votes, it will be adding a new date to history — the day the world’s longest-serving, democratically-elected communist regime will likely shut shop. But for Mamata Banerjee, whose three-decade tirade against the comrades is finally bearing fruit,

history was made, perhaps, on a rather fateful day —March 14, 2007.

On that day, the Left Front government in West Bengal committed its biggest political blunder, ordering 4,000-strong armed forces to storm Nandigram in East Midnapore district where residents were protesting a Special Economic Zone project that would usurp their farmland.

The incident, which left 14 dead in police firing, was so shocking and brutal that it triggered an unprecedented outrage across the state, anguished even the most loyal supporters of the Left and offered Mamata a platform that had eluded her for decades – that of the farmers and the intellectuals of Bengal who made up the bulwark of the Left Front.

Since then, there has been no looking back. She made no mistakes, while her rivals committed only blunders. And for the people of Bengal, who begin voting this Monday, their frenzy around Didi transformed into awe of Mamata.

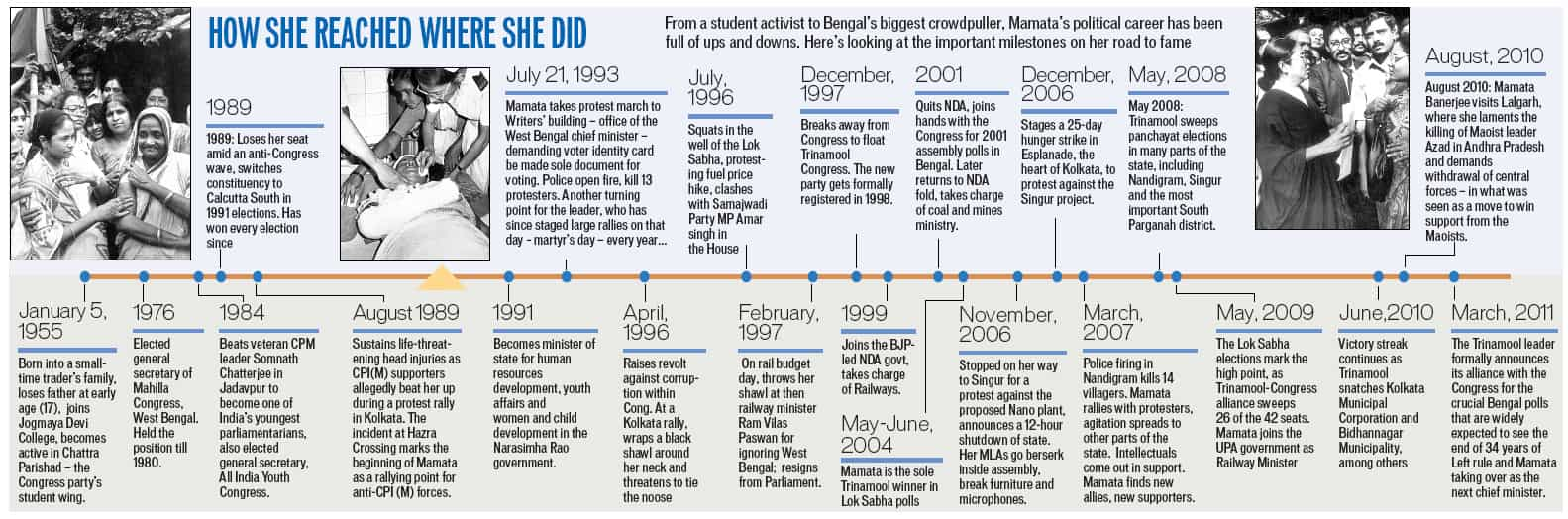

Born into the family of a small-time trader, 56-year-old Mamata’s tryst with politics began when she would accompany her father to political rallies. Her father, a Congress worker, died when Mamata was 17. She chose to relive her father’s dream, joined the student wing of the Congress in college and rose through the ranks.

Spotlight fell on her when she emerged a giant killer in the parliamentary elections of 1984, defeating the indomitable Somnath Chatterjee from Jadavpur. At 31, she became one of India’s youngest MPs, but none of that would change the way she lived and the girl-next-door image she had.

She never left her lower-middle class home in Kalighat, which has an approach road barely five metres wide and is separated from city’s main jail by a reeking, open sewage drain. “Courage and conviction are two words very easy to pronounce, but very difficult to practise. She is a lady who never wore lipstick, never wore a saree that cost more than R 500,” said Trinamool leader Partha Chatterjee who has been with Mamata since her college days.

Mamata’s political ascent coincided with both a growing urban discontent over shrinking economic opportunities in Bengal and increasing infighting within the state Congress whose leaders had given up on fighting the Left.

“She played on the Bengal identity and rebellion within the Congress,” said CPI (M) leader Mohd. Selim. “The mid-90s were also the time when regional parties were gaining ground.”

After her "Clean Congress" campaign failed to remove leaders of the state unit, she split the party in 1997 and replaced it with Trinamool as the main opposition in Bengal. Her desperation to dislodge the Left pushed her to ally with the Bharatiya Janata Party and join the NDA government. A few other flip flops were to follow.

She quit the NDA to form a grand alliance with the Congress and others in the 2001 assembly elections, but the Left swept the polls, managing to co-opt voters with a new leader __ Buddhadeb Bhattacharya. The trend stayed through parliamentary elections of 2004 and the assembly polls of 2006, leaving Mamata grappling in political wilderness.

But as the turn of events would have it, she didn’t have to wait for long to strike back. In the days and weeks that followed the March 14 carnage, Nandigram turned into a war zone. Not far away, another farmer’s agitation had been raising its head to stop the Tatas from building the Nano plant on Singur’s fertile farmland.

An arrogant government ignored the writing on the wall, even as hundreds of thousands of Bengal’s intelligentsia, for the first time in decades, took to streets. Their anger needed a voice, and a leader. And Mamata was there.

She could see her Ma, Mati, Manush campaign coming to fruition. Her party swept the panchayat polls in 2008, elections to Lok Sabha in 2009 and the municipal polls that followed. Now it’s a matter of days for her to realise her long-cherished goal – laying siege to the Writers’ building in Dalhousie square.

Until Nandigram, Mamata was seen, at best, as the only opposition Bengal had to the monolithic CPI (M), but few believed she could actually steer Bengal out of the Left’s hostage. Her detractors dubbed her as a protester in perpetuity who suffered from a deep sense of persecution.

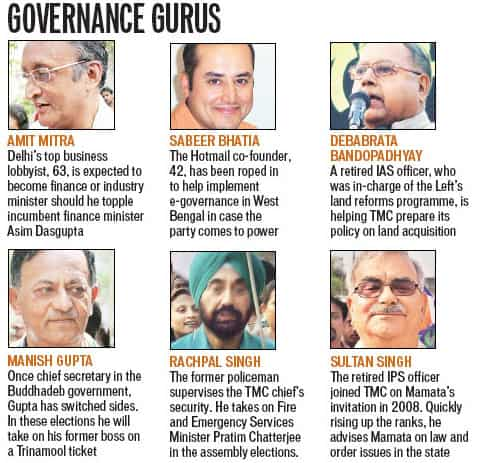

In recent years, though, Mamata and her aides have worked to change that image. She has learnt to be patient, smiles a lot more than she did and is willing to accommodate diverse views. To silence her critics, who often described Trinamool as an apology of a party, she has picked old friends and new allies to create a structure and an organisation (see graphic).

Last month, her party released a manifesto that surprised many with its rigour and details.

Still, there is skepticism if Mamata can really pull Bengal out of the mess. Almost every part of the state is in turmoil; the exchequer is so stretched that the new government may not have money to pay salaries; and worse, several Trinamool leaders are already displaying the arrogance that did the CPI(M) in.

Mamata is aware of the challenges.

"We are not selling dreams ," she said recently. "We have to work very hard to meet the aspirations of the people." That said she is the change Bengal has no option, but to embrace.