In the heart of darkness

Even as Naxals expands their base, Harinder Baweja and photographer Ajay Aggarwal visit Chhattisgarh, the heart of Mao land, to bring us this ground report. In pic: Where guns bleed | The thin red line gets thicker

Nisar Mohammad, Commandant, 170 Battallion, runs what he calls a 24/7 air traffic control, deep in the jungles of Bijapur, Chattisgarh, where the CRPF and the Naxals are locked in an intense game of hide and seek. This game, results in death more often than it does in a catch and so, Mohammad is constantly on the wireless, enquiring if his jawans are dead or alive. Stepping out of the camp — on patrols, and cordon and search operations — is laden with risk and the troops can get ambushed or blown up in a landmine explosion. Even within the confines of the camp, danger lurks. The camp can be run over, any minute, and so the troops have to sleep with loaded automatic rifles within handy reach on their beds. They have also been trained to assemble and load their weapons, blindfolded. The rifle is their anthem and, borrowed from an American soldier in Vietnam, they are told, "This is my rifle. There are many like it. But this one is mine. My rifle is my best friend. It is my life."

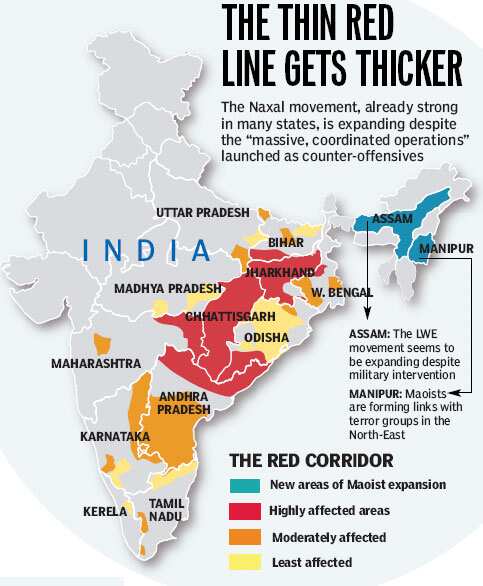

Nisar Mohammad could have been in any of the Naxal hot spots with his men and rifles. In Jharkhand or Orissa. Or Maharashtra and West Bengal. The jungles, across ten states, are swamped with uniformed men, wielding state-of-the-art automatic rifles, mortars and rocket launchers but despite the'massive and coordinated operations', launched over two years ago, the red corridor is only expanding. Early this year, the security establishment celebrated the dip in the violence graph — 142 security personnel killed in 2011 as compared to 285 in 2010; 216 police informers killed in 2011 vis a vis 323 the previous year; and 131 attacks on the police as against 230.

The celebrations, however, were short lived as the first three months of this year saw abductions of two Italian men and an MLA in Odisha and the deaths of 12 CRPF men in Gadchiroli, Maharashtra. As Ajai Sahni, executive director, Institute of Conflict Management, says, "a decline in fatalities is not synonymous with decline in rebel capacities or with improvement in the 'security situation'." Home Minister P Chidambaram understood this and perhaps looked at the same figures and realised that the Naxals too had taken less hits — 99 killed in 2011 compared to 172 the previous year. Chidambaram, in fact, cautioned the chief ministers this week, at the internal security meet when he said, "Decline in the overall number of casualties among civilians and security forces in Left-Wing Extremism-affected districts may give a false sense of assurance, but that is not the true picture."

The true picture can be found in Ground Zero; far away from the state capitals of Raipur, Bhubaneswar and Ranchi. Far, also from the portals of North Block that houses the offices of the ministry of home affairs.

New milestones at ground Zero In Bijapur, we are driving along a slim metalled road; ostensibly National Highway 16, but the 21 kms has only just been constructed — under the supervision of gun-wielding security personnel — and it has its own milestones. "Ma'am, this is what we call ambush point. This is where we lost seven men," says a voice in the dark as we drive down the road where turning on headlights is inadvisable. A little further is where 12 were killed in an explosion and just ahead, another milestone: the place where a jawan died of a heat stroke. The temperatures soar and here, in the thick jungles of Bijapur — one of the worst Naxal-affected districts, which is 70 percent forest — there is no guarantee that you will die a 'martyr'. A bullet or blast kills instantly; but cerebral malaria, easy to contract is slow and painful.

But the crucial question, often unasked, — who are these men hunting for? Is a military offensive the solution or is it only a part of a solution that must go hand in hand with development and land rights, to stem the expanding influence of the Naxals. The bitter truth — in ample display in Ground Zero — is that well trained paramilitary battalions are being pumped in but these men, drawn from far away Haryana, UP and Tamil Nadu, neither know the terrain, nor the language. As one officer said, "We are doing what the local police should be and we have the hard task of motivating men who we are literally throwing at death's door."

Veteran policeman KPS Gill, acknowledged to be the man who brought peace to Punjab whilst earning the dubious reputation of being a killer cop, is not surprised that more swathes of territory are being ceded to the Maoists. The same man, who presided over a reign of dubious fake encounters in Punjab believes that while operations were necessary there, in the red corridor the strategy has to be multifaceted and development lies at the heart of any solution, provided the tribal is viewed as its principal stakeholder.

The troops are lucky to have malaria kits for timely detection but what of the tribals, the dalits? Nearly half a billion live in the six worst affected states and they lie at the heart of the Naxal conundrum; of what the Prime Minister has often referred to as the biggest internal security threat.

Guns on either side

The tribals live a destitute life, devoid of basic amenities, liberty and self respect. Ironically they live in a mineral-rich zone, horribly caught in a cycle of violence that flows from two sets of guns. And if they tend to tilt towards the armed revolutionaries, it's not entirely out of fear.

Imagine being a resident of village Budagudi, undiscovered by the surveyor general, the census department, the health official or a government. Imagine the security forces charging into your thatched hut by first light and questioning you because the medicine box has tablets that indicate that perhaps the Naxals had made a stop there. Imagine being part of the people's court in Odisha where the kidnapped MLA Jhina Hikaka is being tried.

The tribals live that life, day after day and that's the reason why even KPS Gill says, the problem is as much the Naxals as it is the administration. If the locals veer towards the armed rebels, it is because they want food, clothing, education, health facilities and legitimate rights over the land that is theirs. And if the paramilitary forces are living a dog's life, hunted day and night, it's because they've been forced into an inhospitable war theatre where they don't know who they are battling and who they have been forced to declare war against. So alienated are they from their own people, they have been instructed not to drink water from the villages, lest it be poisoned.

Gill, who was personally called by Chief Minister Raman Singh to be his security advisor, was famously told to sit back and relax within a week of joining. He knows and believes that the troops are stuck quite like the Americans are in Afghanistan. Raman Singh did not take a single suggestion from the plan Gill drew up; instead the top cop soon realised that the senior men in uniform in Bastar were taking money from constables to post them out of the red corridor.

The simple strategy, being applied across the ten states, is — clear, hold and develop — but the equally simple and stark reality is that neither have the forces been able to clear nor hold. The minute the CRPF or the BSF return to their posts, the Naxals return to the areas vacated by them. This cold, yet alarming statistic should, therefore, come as no surprise to the policy establishment: in a reply to a question in Parliament, the home ministry admitted that as many as 46,000 officers and personnel took voluntary retirement from the paramilitary forces between 2007 and September 2011, while another 5,220 resigned from service over the same period. 461 suicides and 64 instances of fratricides were also recorded.

Battalion Commandant Nisar Mohammad has felt this vulnerability first hand. His battalion has 48 jawans who are listed in the lower medical category with several ailments and he has three men who have been taken off combat duty because they are psychologically disturbed. His battalion is also full of troops who prefer a posting in Kashmir over their current tenure in Mao land. This happens when the State chooses brutal suppression over the development model. It happens also when political satraps occupying the all powerful chair of the chief minister dismiss the tribals, their own people, as unattractive vote banks. It happens when desperate pleas from IG CRPF, Pankaj Kumar Singh, for basics like equitable distribution of ration to the tribals and more roads, are ignored; when mobile towers are not even being put up within police posts because its considered too risky and worse, because the argument is the network will be used by the rebels. Nobody is thinking, people.

The Centre and the States need to ponder and redraw their strategy and ask why Assam has been added as a new state on the Red map. They need to aggressively work towards the tribal being the true stakeholder. Till then, Nisar Mohammad's wireless will keep buzzing with high voltage tension. And his men will only have rifles for sleeping partners.

Other dark states

Maharashtra

Odisha's hostage crisis has had a cascading effect in Maharashtra. The police sounded a red alert in areas bordering naxal-affected districts. Sunil Ramanand, DIG Gadchiroli range, who is monitoring the anti-naxalite operations, said check-posts and borders have been strengthened. Para-military forces and district police have been deployed to prevent infiltration by the LWE from Chhattisgarh and Odisha. The Gadchiroli police are on their toes after the the Pushtola incident where the Maoists ambushed a CRPF convoy, killing 13 jawans. Three villagers and an NCP leader were also killed this month after they were branded as police informers. The district has even witnessed a series of attacks recently that claimed the lives of many policemen.

The police have set up a separate cell to co-ordinate and monitor anti-naxalite operations. The administration has asked all politicians, government officials and social workers not to venture into the interior areas without informing the police department for fear of kidnapping.

Pradip Kumar Maitra

Jharkhand

Maoist guns are refusing to go silent in Jharkhand despite anti-Naxal operations. Eighteen of the 24 districts in Jharkhand are Naxal-affected. The rebels have killed around 443 security personnel and 1200 civilians across the state in the last ten years. They have seized vast tracks of cultivable land in some of worst affected districts and distributed it to poor peasants. But the state police and the CRPF together have also dealt severe blows to the Naxals. CM Arjun Munda claims that security forces have killed 574 rebels and arrested over 1000 Maoist guerillas and their sympathisers during the last decade.

Director General of police (DGP) G S Rath claims they have destroyed several Maoists hideouts. "They are frustrated and a weaker force now," he says.

Anbwesh Roy Choudhary

Odisha

The Maoists may have rattled the Odisha government with the high profile abductions of two Italian citizens and a ruling party MLA, but the police are trying to put up a brave face. "Abducting soft targets indicates the rebels' moral is low. This shows how desperate they are'" says Odisha's IG (operations) YB Khurania, adding that security forces had notched up several successes against Maoists in recent years.

According to state home department figures, the police killed 23 Maoists in 2011 as compared to 12 in 2010. In 2010, 45 Maoists surrendered while it rose to 50 in 2011. A total of 170 Maoists were arrested in 2011, while the figure was 148 in 2009.

On the other hand, Maoists killed a total of 77 civilians and policemen in 2010. It came down to 51 in 2011.

Priya Ranjan Sahu

Photo Gallery: