Back to school

India’s enrolment numbers have gone up, yet many girls don’t end up going to school for various reasons. The six finalists in this category aim to bring such adolescents back to the classrooms.

India’s enrolment numbers have gone up, yet many girls don’t end up going to school for various reasons. The six finalists in this category aim to bring such adolescents back to the classrooms.

PROTSAHAN INDIA FOUNDATION, NEW DELHI

Protsahan India Foundation (PIF) uses creative arts such as design, photography, technology and cinema to encourage and empower vulnerable, at-risk and marginalised girls. The NGO, which was started in 2010 by Sonal Kapoor, has three programmes for adolescent girls: Educare (a bridge course using creative arts), the core programme, works with out-of-school children between six and 17 years. Under Educare, Protsahan runs a bridge course for 10-14 months, with the aim of re-enrolling school dropouts into mainstream government schools. The programme emphases on functional literacy and is being run in three urban slums in Delhi and Pune.

"Our second project -- Street Micro Entrepreneurs -- focuses on Vocational Training. Girls rescued from abusive homes, streets and slums. They are given skills-based training to enable them to pick a vocation and earn a sustainable living," said Kapoor. The organisation also imparts education on child marriage, sexual violence, need of toilets and menstrual hygiene management.

"If at risk and vulnerable adolescent girls and children are educated and empowered using creative and unique teaching methods then they can access mainstream education, acquire life and livelihood skills to become independent and financially sustainable," added Kapoor. "But most donors don't understand the importance of encouraging dignity of a little abused child through creative technology, design and art vis-a-vis rote methods of education. This is what Protsahan aims to transform. If adolescent girls are empowered creatively, then they can break free from the inter-generational cycle of poverty, abuse and violence".

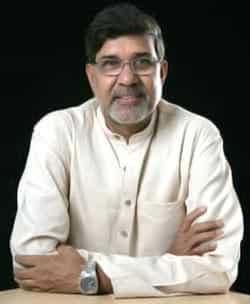

BACHPAN BACHAO ANDOLAN (ASSOCIATION FOR VOLUNTARY ACTION), NEW DELHI

Bachpan Bachao Andolan (BBA) was India's first civil society campaign against the exploitation of children. It was set up in 1980 and to date has touched the lives of 80,000 young people. One of the key initiatives of BBA is its Bal Mitra Gram (BMG) programme, an innovative development model to combat child labour, protect child rights and ensure access to quality education to all.

"A few years after we started BBA, we realised that to combat child trafficking and labour we must address the source of the problem: villages since nearly, 70% of child labourers come from villages. So we decided to create an environment where children are withdrawn from the workplaces and attend school," explained Kailash Satyarthi, founder, BBA.

With this aim in mind, he started BMG, which are essentially model villages that are free from child exploitation and promote child rights. Since 2001, BBA has transformed 356 villages as child friendly villages across 11 states.

In BMGs, BBA ensures that children up to the age of 14 have access to free, universal and quality education and schools have proper infrastructure so that girls don't drop out.

Renu Kumari, a girl activist from Palmo village of Jharkhand, is a beneficiary of the programme. She used to collect mica with my parents and even though she was enrolled in a school, she never attended it.

"My parents started sending me to school after BBA activists came to my village. Many of my friends have also started attending school. We have also formed a children's council where we discuss issues related to child labour, education and issues related to children," she told HT. "Today, no children in my village go to the mines to work rather all are in school."

CENTRE FOR COMMUNITY ECONOMICS AND DEVELOPMENT CONSULTANTS SOCIETY (CECOEDECON), JAIPUR

The Centre for Community Economics and Development Consultants Society (CECOEDECON) was started by a group of young social workers to provide relief to the victims of devastating floods in Jaipur in 1982. From a modest beginning as a relief agency, CECOEDECON today has evolved into an organisation that works across numerous sectors including education, health and livelihood.

One of its recent programmes includes working with adolescent girls to ensure their development. However, CECOEDECON does not have one single umbrella programme to address the issues that adolescent girls face; rather it attempts to address these challenges through a number of inter-related programmes like providing education to out-of-school girls through a bridge course and then mainstreaming them into formal schools.

It also conducts a one-year residential school where girls between 14 to 18 are given a quality formal and non-formal education, taught lifeskills, trained in income generating activities, and health-based training (including training on physical developments in adolescence and nutrition). The girls are also trained in women's rights and laws. Along with education, it also imparts vocational training to girls and provides non-formal education to victims of trafficking.

"The social and cultural dimensions of our work area in Rajasthan pose many hurdles in achieving the goals of the programme. The continuity of the positive impacts of our interventions are often affected, due to factors like early marriage, illiteracy and lack of exposure to the mainstream which lead to change in the beneficiaries' priorities while also limiting the options available to us, said Sharad Joshi, chief executive, CECOEDECON.

CENTRE FOR UNFOLDING LEARNING POTENTIALS, JAIPUR

Even though India has achieved high enrollment rates in primary education, girls, and marginalised groups such as the very poor and the disabled, are often left behind. While girls attend primary school in roughly equal numbers to boys, the gap widens as they get older and more are forced to drop out to help with work at home or get married.

The Centre for Unfolding Learning Potentials (CULP) focuses on the education of such out of school children (OoSC), especially adolescent girls, and ensures their re-enrollment in government schools. The organisation also focuses on improving the quality of education in government schools and mobilising the community to create a positive environment among rural communities towards girl child education.

The organisation utilises the existing resources of the State schools and establishes linkages with the Sarva Sikhsha Abhiyan for leveraging resources and ensures that the community participates in the project for developing a feeling of ownership in school," said OP Kulhari, co-founder and secretary, CULP.

About 1.6 lakh adolescents have been benefitted under the project since 2002 in four districts of Rajasthan and this includes one lakh adolescent girls.

But persuading parents of adolescent girls to allow their wards to go to school has never been easy. Take for example the case of Vaijanti Meena of Trilokinathpura, near Jaipur. A scheduled caste, she belongs to the BPL category. She never went to school but when she was 14, the organsation persuaded her parents and in-laws to allow her to join a bridge course. She now studies in a college in Japipur. "She dreams of joining the Rajasthan state service and is now pride of the family," said Meena.

DEVELOPMENTAL ASSOCIATION FOR HUMAN ADVANCEMENT, Uttar Pradesh

Bahraich in Uttar Pradesh is one of the 100 most-backward districts of the country. For the last 24 years, the Developmental Association for Human Advancement (DEHAT) has been working here with children and adolescents on education, health, advocacy, livelihood and empowerment. The organisation executes four programmes for adolescent girls: education, health and nutrition, changing community perception towards girl child and reduction of child marriages.

For adolescent girls, DEHAT executes its programme with four main objectives: educate and empower girls; ensure health and nutrition of adolescent girls; change community perception towards girls and reduce girl child marriages.

The empowerment programme is run through a robust Kishori Mandals (adolescent girls groups) and child rights forums; child rights forums (adolescent girls and boys groups): empowerment groups formed within communities to discuss gender-based issues.

To educate rural girls, Dehat has set up education centres for adolescent girls who were never enrolled in or dropped out of school. Along with teaching them the basics, classes are also held on empowerment and health issues.

The Swabhiman programme aims to reenrol girls who have dropped out of school after Calss 5 and help them clear class 10th exams.

DEHAT deals directly with the community as an implementer of the education programme. Community-elected teachers facilitate the programme and community-based organisations closely monitor the programme, enabling DEHAT to gradually withdraw its presence typically over a period of five years, thereby letting the community take greater ownership. As a result, the organisation can reach out to many beneficiaries with minimum staff support.

IBTADA, ALWAR

The Mewat area, which is dominated by Meo Muslims, is characterised by low education levels and poor status of women and girls and hence Ibtada works especially to empower these groups.

Ibtada has two main areas of focus: women's empowerment and education for girls.

"Meo Muslims are conservative and they prevent girls from going to school. In the initial days of Ibtada, many community/religious leaders did not allow us to intervene for girl's education. Ibtada was also targeted by clerics. Getting girls to learning centres was extremely tough initially, but now things have changed," Rajesh Singh, executive director, Ibdata told HT. The organisation has set up learning centres --- taleemshalas --- near villages so that girls can access them. Taleemshalas cover learning up to Class V using the state curriculum to teach all subjects, after which girls are mainstreamed into existing government institutions. To ensure the girls receive quality education, Ibtada has developed its own workbooks. One taleemshala typically has up to 30 girls from different learning levels.

The changes are evident now: Ayeena, a school dropout, joined a taleemshala in 2004 at the age of 13. She finished her class V in 2006. Her parents wanted to get her married but she resisted. She sought support from Ibdata staff and local SHG who then talked to her mother, who was also a group member. Finally, the family was ready to send her to upper primary school. Ayeena did well in studies and cleared Class XII in 2011 and is now the final year of graduation.