10yrs after tsunami, India still needs to fill in disaster management gaps

Then, tsunamis were missing from the mandate of the Met department. There was no warning system. Ten years later, India looks better prepared although some serious gaps remain. Asian tsunami

On the morning of December 26, 2004, the waters were still placid when Jeevitha Chettiar, then 18 years old, saw her fishermen brothers Anmugam, Ravikanth and Padiril head off towards an ocean that was about to swallow them up.

Few in Chettiar's coastal village in Cuddalore, 180 km from Chennai, survived the tsunami, as the Indian Ocean begun to heave violently from a 9.15-magnitude quake off the Sumatra (Indonesia) coast. The planet shook for 10 minutes, releasing energy equivalent of 23,000 Hiroshima bombs.

It wasn't just Chettiar's village that woke up to a disaster. Over 2,26,000 people were killed in 13 nations, including 12,405 in India.

Then, tsunamis were missing from the mandate of the Indian Meteorological Department, the nodal agency that monitors natural events. There was no warning system and budgetary support to prepare for a tsunami.

"We never knew the ocean could leap towards us in such a way," says Chettiar, the well-known face of Swept, a documentary film on the tsunami.

Ten years later, India looks better prepared although some serious gaps remain.

After 2004, India mounted a sophisticated warning system -- required by international obligations -- under the Hyderabad-based Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Sciences. By 2007, the Indian Tsunami Early Warning Centre (ITEWC), along with a 24/7 National Tsunami Warning System, began operations.

The ITEWC has harnessed advanced tools, such as a real-time seismic monitoring network of 17 broadband-based stations and under-sea equipment, apart from collaborating with similar international stations to detect tsunami triggers from the two known trouble spots, called subduction zones, in the Andaman-Sumatra and Makran sectors of the Indian Ocean. A tsunami triggered in these zones can potentially affect the Indian coastline.

India is looking to fuse its tsunami detection model with those of other nations, such as the US. The country has arrangements with the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) to compare its performance with the US model.

But ensuring that deaths and losses are at a minimum in the event of another tragedy would require the government to go beyond technological fixes, experts say. This is because forecasting is just one aspect of disaster mitigation. The country requires much more for well-rounded protection.

For example, authorities have paid scant attention on building "resilient infrastructure" and "resilient coastal communities". The former includes ecological barriers, such as coastal forests, which can considerably cushion the impact of slamming waters, and infrastructure that can survive such disasters (tsunami-safe housing and multi-hazard shelters). The latter includes disaster preparedness training for coastal communities.

"After the tsunami, the government started training coastal communities on what to do once disaster strikes. But training stopped after a few years. I have forgotten everything," says Kalimar Ratnavil of the Legal Aid to Women Trust, an NGO in Nagapattinam, one of the worst-hit districts in 2004.

Close to 40% of India's population lives within 100 km of its 7,000-km coastline that is vulnerable to disasters. Studies show that losses from natural disasters equal 2% of India's GDP each year.

Coordinating an effective top-down response is difficult and time-consuming and so training communities is so vital. Unlike in Japan, there are no regular mass drills; or dedicated airstrips for large planes to evacuate people quickly.

Coastal regulation zones are yet to be strictly enforced.

"While technology is critical, the government has done little to manage its coastline to comply with minimum-damage norms," says oceanographer and former professor of Maryland University, Harish Athale.

Experts say fishing communities need to be housed on the landward side of coastal roads. A centrally sponsored scheme for welfare of fishermen has no provisions for enforceable tsunami-safe housing. There is no national-level programme for natural protection safeguards that can greatly reduce a tsunami's fury, such as mangroves and casaurina plantations.

Warning systems work only when people receive information well in time. While India has been fairly successful in handling cyclones, which are lazy systems that take a lot of time building up giving authorities enough time, tsunamis are quite sudden.

Experts say India will have no more than two hours' reaction time for mainland evacuation, if a 'tsumanigenic' quake were to strike the two known Indian Ocean trouble spots. For Andaman & Nicobar Islands, the reaction time is less than 30 minutes.

In some places in Tamil Nadu, even the basic minimum preparedness is missing.

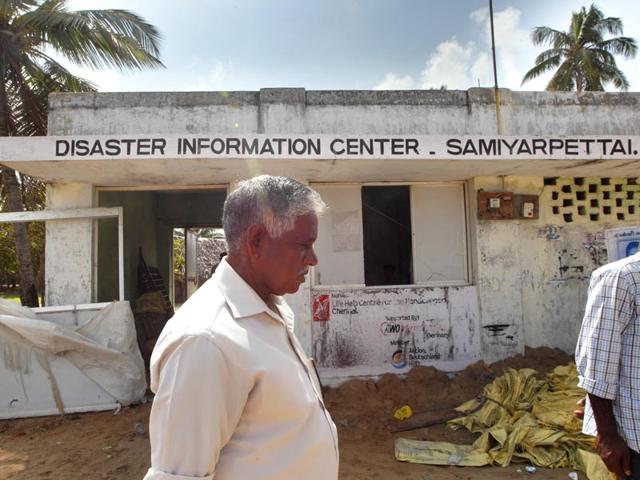

"The public address system does not work and in case of any warnings or alerts, the police comes over," said Lenin Shekhar, who was visiting his home at Samaiyarpetti, Cuddalore.

The village's 'disaster information centre' is now defunct.

In Nagapattinam's Akkairapeit, locals complained that that the government is yet to install sirens or a public address system.

After the tsunami, the government built multi-hazard shelters. While some of them are in good condition, the HT team found several in dilapidated state like the one in Tangambadi in Nagapattinam.

"We have 31 shelters and are building 18 new ones. Of the 31, 19 will be repaired at the cost of Rs. 91 lakh," says T Munuswamy, collector, Nagapattinam.

He added that the government has built roads (for quick evacuation); pucca buildings for sea shore villages and started a tsunami warning SMS service for villagers.

But in many villages, in both Nagapattinam and Cuddalore, residents complained that either these shelters are located too far from their village or too small for the population they are meant to cater to.