Treatment of caste sets apart India’s constitutional vision

At India’s founding, Parliament functioned as a dual-purpose body, legislature by morning, and as Constitution drafters by afternoon

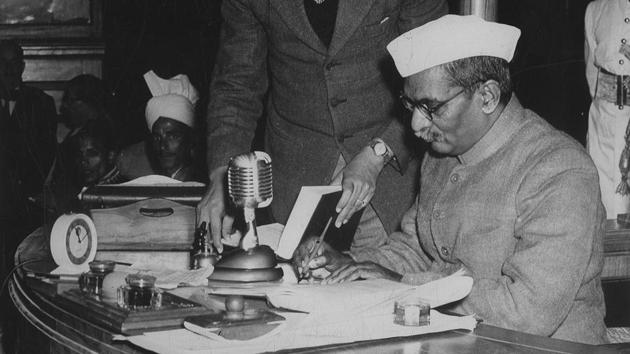

One of the most vivid images that symbolised a constitutional India is a beaming Bhim Rao Ambedkar, handing over the draft Constitution of India to the president of the Constituent Assembly, Rajendra Prasad, on November 26, 1949. India’s Constitution was adopted and a new beginning would commence for an ancient land comprising multiple civilisations. I have often looked at this picture of the handover of the Constitution, wondering at the emotions that must have raced through the mind of the Chairman of India’s drafting committee, at a project that was both complete and commencing at the same time. The project that is Constitution crafting was complete, but the journey that would be its interpretation and implementation to build a new country would begin.

Seventy years later, if Ambedkar came to visit us, would he still be smiling as broadly as he did on that day?

Through this journey, India and her Constitution have confronted many complex challenges. These challenges are two kinds: one set that have endured from India’s founding, and the other that are contemporary ones defined by present-day politics. Let us first discuss the founding challenges that have persisted, and constitutional techniques from 1940s that continue to stand us in good stead today.

At India’s founding, Parliament functioned as a dual-purpose body, legislature by morning, and as Constitution drafters by afternoon. It did so amid Partition, and thousands of refugees flooding into Delhi, many as close as Purana Qila a few kilometres away. I can’t resist wondering what this hard working legislature would have made of the low quorum seen sometimes during discussions on key bills, and a culture of promulgation of significant laws through Presidential ordinance?

But, let me not digress. From 1946 to 1949, as the Constitution was being drafted, India faced three founding constitutional challenges. The first stemmed from Partition; its resultant communal violence; and therefore within the Assembly, the resolution of questions of identity and faith. Would we be a Hindu nation in contrast to Pakistan being an Islamic state? This was answered with an unequivocal no with a commitment to a Constitutional Republic with no state religion and an equal freedom to practise all religions. The drafters also chose not to insist on a homogenous vision of a nation; for instance, while Hindi was made the “official language of the Union”, English was retained to be used for all “official purposes”. When debating the adoption of Hindi as a national language, on September 12, 1949, Rajendra Prasad, said that the choice of national language would have to be “carried out by the whole country”. And that “even if a majority of the Assembly made a choice which was not approved by a section of the people, then, implementation of the Constitution would be rendered perilous”.

The second set of challenges stemmed from the dramatic constitutional vision that aspired to build a different society; not merely a new nation. While nationhood was about territory and recognition of sovereignty, a new society is created through a break from older values. The Constitution’s breaking away from old India came in the form of values of equality and non-discrimination on grounds of sex, race, religion and caste; and universal adult franchise for all, women and men, lower and upper caste, rich and poor. For a society where opportunities were segregated by gender, caste and religion, this break from the past, finally meant recognition of an equal individual dignity.

But it was the treatment of caste that would truly set apart India’s constitutional vision. By recognising the terrible brutality and cost of societally sanctioned caste segregation, and then making actual reparations by providing for reservations in educational institutions, political constituencies and public employment for members of scheduled castes and tribes, the framers set themselves apart as revolutionaries. Making reparations is a uniquely Indian constitutional value. By contrast, for its past brutalisation and profiteering from the enslavement of African Americans, US constitutionalism makes no reparations or amends of any sort.

Despite there being support for the practice of caste, for it is a core part of Hinduism, the Constitution clearly establishes its morality as being distinct from that of societal and majoritarian morality. It would be this constitutional pathway breaking from societal and majoritarian morality that would lead contemporary India to the constitutional emancipation of LGBTQ communities.

For its deep investment in breaking from the past, the Constitution gained fierce support from new constituencies that were erstwhile left out of political conversations: Women, “lower castes” and minorities of all sorts — religious and sexual. This has expanded the constituencies that believed in the Constitution and that became deeply invested in its success and consolidation.

Today, the Constitution faces two kinds of challenges. The first are familiar ones from the days of our founding that implicate faith and religious practice. In contemporary India, they take the form of challenges like the entry of women into the Sabarimala temple, or the recently adjudicated Ram Janambhoomi-Babri Masjid title dispute.

The second set of contemporary constitutional challenges is shaped by the ability of the powerful to shape political opinion. The movement that shaped India’s founding was built on large meetings, padyatras, satyagrahas and jail terms. The resultant constitutional aspirations reflected the diverse people who marched along side each other. Today, the concentration of wealth and questions of election funding enable the shaping of skewed political opinion. It reflects the opinion of powerful but homogenous interests. This implicates freedoms of speech, press, expression and democracy — all of which are part of the basic structure of the Constitution. The endurance of India’s constitutional values will be determined in large part by an accurate telling of her successes and failures.