Top kabaddi players, wrestlers lead sporting twist to farm agitation

Vijender Singh, India’s first Olympic medallist in boxing, also went to the protest site on December 6. Unlike many of the other athletes at the site, he has clear political ambitions, but the man from a village called Kaluwas in Haryana is also intimately connected to farming.

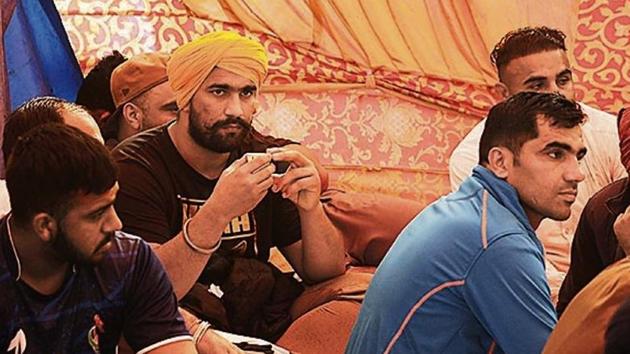

To get to the main stage at the massive farmer’s protest at the Singhu border between Haryana and Delhi, one has to go through a formidable man called Sukhjeet Singh. Built like a tank, with a neck as thick as a truck tyre, Sukha Bhandal, as he is better known, is one of India’s most celebrated Kabaddi players. In rural Punjab and Haryana, he is a household name. Songs are written about him. His other moniker is “sher” (lion) and he has sprawling lion tattoos on his back and arms. His annual earnings from tournaments easily makes him worth millions.

“I was part of the protest from Day 1, when farmers started agitations at the district and state level,” he said. “Later, when they decided to march to Delhi on November 26, I joined them.” Sukhjeet is not the only sportsperson who is a part of the agitation; among the protesters at this border is a large contingent of some of the biggest stars of rural sports in northern India; kabaddi exponents and wrestlers who draw crowds in their thousands at dangals, the traditional kushti competitions.

Vijender Singh, India’s first Olympic medallist in boxing, also went to the protest site on December 6. Unlike many of the other athletes at the site, he has clear political ambitions, but the man from a village called Kaluwas in Haryana is also intimately connected to farming.

“There is no way that anyone from our rural areas would not be part of the protest,” Vijender said. “My grandfather was a subedar in the army and the one who brought boxing to our village. My brother Manoj fought in the Kargil war. My father was a driver with Haryana Roadways and I am into sports. But our entire family is linked to one common profession -- farming.”

The protests have seen participation from several other mainstream sportspersons. On December 6, Kartar Singh (wrestling), Gurmail Singh, Rajbir Kaur and Ajit Singh (all hockey Olympians) and boxer Jaipal Singh shared the stage with Vijender and announced their intention of returning their Padma Shree, Arjuna, Dhyanchand and Dronacharya awards.

Like Vijender, Sukhjeet, too, is deeply rooted to the land. Two decades back, when he was 14, he lost his parents in the space of a year. One of three siblings, he found himself alone at the family’s farm in Bhandal Dona village in Kapurthala. His sister had married and left, his brother had migrated to Germany. Despite their requests to join either of them, Sukhjeet decided to stay back and try his hand at managing the farm. It also allowed him to pursue his passion, kabaddi. “Farming has given me everything,” he said. “So how can I not be here?”

If there’s one thing sportspeople know well, it’s organisation and team work. At the Singhu protest site, which sprawls nearly 15km along the highway, that collaborative discipline has been critical. When the protesters’ plan to march to Delhi was blocked, and the highway became the site of protest, the kabaddi players were involved in arranging for tents. “We entered Haryana on November 26 evening and our night halt was near the Panipat toll plaza. Next day, in the morning, we moved towards Delhi, but as the border was sealed, we had to stop at the Singhu border,” said Mangat Singh aka Mangi Bagga, who is as well-known as Sukhjeet. At the inaugural Circle Kabaddi World Cup (circle kabaddi is the more popular rural version of the sport in Punjab) in 2010, Mangat was the Indian captain. “We took help from our kabaddi friends in Haryana and arranged for tents and material for the stage.”

Kabaddi players and wrestlers from Sonepat (Singhu border falls in Sonepat), India’s pre-eminent wrestling belt, also pitched in with public address systems.

Kabaddi player Sandeep Nangal Ambian, who came to Singhu with his colleague Sultan Samspur, driving a truck packed with fruits meant for distribution at the protest site, said “senior kabaddi players have made an appeal to all the players to join the protest. At any given time at Singhu and Tikri borders, you would see more than 100 kabaddi players and other athletes giving their services to the movement.” Athletes from the famed wrestling village of Mandothi, near Haryana’s border with Delhi at Tikri, which has turned into another protest site, are running a kitchen.

“It’s a fight for a common cause,” said kabaddi player Viney Khatri, 23, whose village Kharak Jatan in Rohtak is 80km from Tikri border.

Wrestling and kabaddi enjoy immense cultural popularity and a thriving socio-economic niche in rural northern India. The overseas (Canada, England, US) and domestic circuit of circle kabaddi is valued at approximately Rs100 crore just in terms of the prize money on offer, according to Sandhu and several athletes. This year, both the season and its robust economy was left in tatters by the pandemic. The foreign season was cancelled in its entirety, while the domestic season limped into action late in October with a heavily reduced calendar. The farmer protests have meant that even this diminished season has been further curtailed.

“If the farmers prosper, then the village will prosper and only then can we (athletes) earn well,” said Mangat. “So, the economic cycle begins with the farmers, We have requested the players and organizers to put a hold to tournaments. Right now, this movement is more important than kabaddi.”

Jaskanwar, who is a mountain of a man with a full beard and a luxurious moustache upturned at the ends said that with his entire family involved in protests, he found it hard to think about sports.

“I have sent my refusal to many dangals,” he said. “We can earn later, but for us, this is a revolution.”