The soul of Sabarmati: As the Gandhi Ashram in Ahmedabad completes its centenary year, a look at the place it had in the Mahatma’s life

The Satyagraha Ashram on the banks of the Sabarmati was founded by Gandhi on June 17, 1917.

A couple of international tourists, guide in tow, wipe the sweat off their brows as they step inside the air-conditioned exhibition area of Sabarmati Ashram in Ahmedabad. The heat outside is difficult to bear even for locals used to the worst of Indian summer. But the blistering June weather fails to keep away visitors – both domestic and international – from the Ashram founded by Mahatma Gandhi on June 17, 1917, which served as his residence for the next approximately 13 years till 1930. This Sunday (June 17) marks the end of the Ashram’s centenary year.

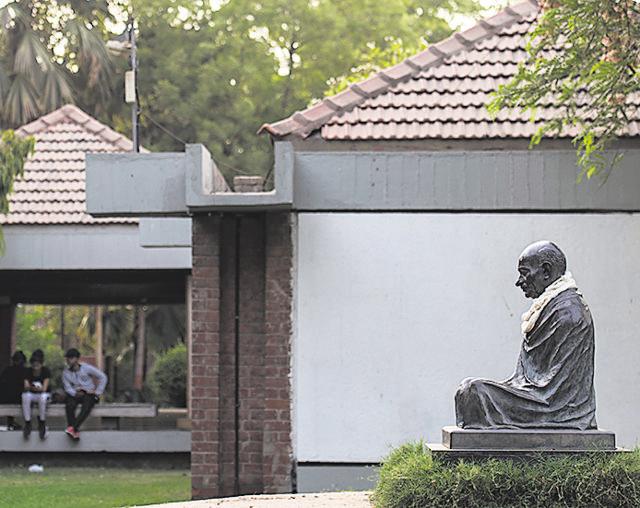

“We get more than 4,000 visitors a day,” says Atul Pandya, director, Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust. “The main attraction is Hridaykunj, Gandhiji and his wife, Kasturba’s living quarters at the Ashram.” The rest of the Ashram consists of Vinoba-Mira Kutir, a small hut that served as the residence, at different points, of Vinoba Bhave (best known for starting the Bhoodaan movement), and of Madeleine Slade or Mirabehn (daughter of a British rear-admiral, who moved to India and became involved in the country’s freedom struggle), Nandini (the Ashram guest house that is today locked and awaiting renovation), the prayer area, Udyog Mandir (where the khadi technology had been developed, now under renovation) and the living quarters of Maganlal Gandhi – Gandhi’s nephew, disciple and one-time manager of the Ashram, which has been turned into a Charkha gallery. The museum, library and exhibition area is a later addition by architect Charles Correa, who has used brick piers, stone floors and tiled roofs to blend it with the rest of the Ashram and there are two book and memorabilia and khadi shops near the Ashram entrance.

Setting Up The Ashram

“… If, on weighing the merits of this Ashram against its drawbacks, it is found wanting, the world has a right and duty to say that I have lived my life in vain as I have attempted to put my whole soul into it,” Gandhi wrote in the 1920s, in reply to some allegations and criticisms against the Ashram.

When Gandhi returned to India from South Africa in 1915, he had already been practising commune living for a while, at the Phoenix Settlement and Tolstoy Farm that he had set up there. But as he himself wrote, neither those who lived there nor anyone else referred to those institutions as ashrams. After his return, there were suggestions for him to settle in various places. But Gandhiji finally chose Ahmedabad for his first Ashram in India because, as he wrote later, “Being a Gujarati I thought I should be able to render the greatest service to the country through the Gujarati language. And then, as Ahmedabad was an ancient centre of handloom weaving, it was likely to be the most favourable field for the revival of the cottage industry of hand-spinning. There was also hope that, the city being the capital of Gujarat, monetary help from its wealthy citizens would be more available here than elsewhere.”

The first ashram in India was set up in Ahmedabad’s Kochrab area in 1915. The place was given the name of Satyagraha Ashram. But it couldn’t continue at that location for long. “For one, the place was too small,” explains Gandhian scholar and author Tridip Suhrud. The Ashram had started with about 20 people, but the number doubled in a few months. There was also not enough space for some of the activities that Gandhi wanted to start such as a tannery, agriculture and animal husbandry. “The second challenge was that with the entry of the first Dalit family of Dudabhai, Danibehn and their daughter Lakshmi, there were protests among the locals,” he says. As Gandhiji has himself written there was some initial resistance both from those within the Ashram and those outside. Funds dried up for a time, as most patrons stopped giving money. “The breakout of plague in Ahmedabad was the final reason that led him to move the Ashram,” adds Suhrud. The site of the Sabarmati Ashram was at the time outside the city of Ahmedabad.

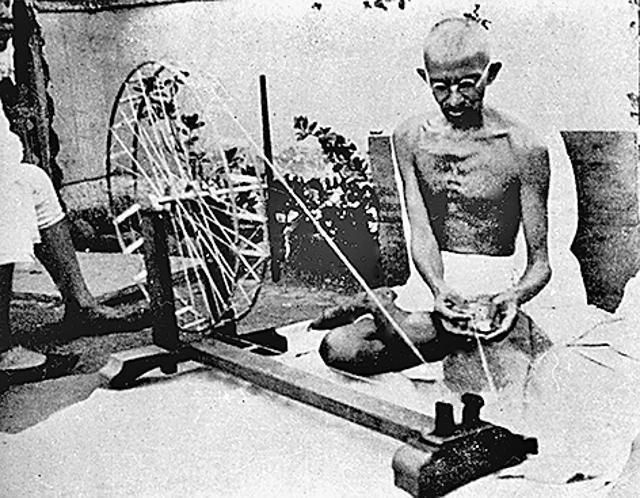

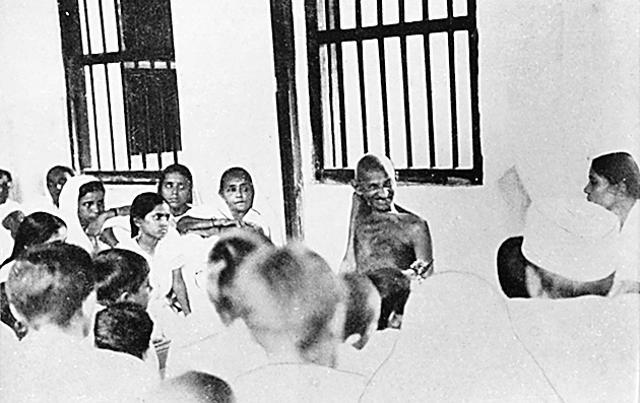

“The plot was between a crematorium on one side and a jail on the other, and this appealed to Gandhiji, since he felt that every Satyagraha activist has to go to both places,” says Gandhian scholar Ramachandra Guha. The Ashram was shifted to the banks of the river Sabarmati on June 17, 1917. Gandhi was in Bihar at the time. Though named the Satyagraha Ashram, it became more commonly known as the Sabarmati Ashram. A Constitution for the Ashram had been drawn up while at Kochrab and ashramites had taken vows that included those of truth, non-violence, celibacy or chastity, control of the palate, non-stealing, non-possession, swadeshi, fearlessness, removal of untouchability, tolerance, manual work. These continued at Sabarmati, though Gandhi would, from time to time, modify them as required, says an Ashram employee. Gandhi’s daily routine, while at the Ashram, consisted of writing, reading, praying, giving speeches, planting trees, spinning, cleaning toilets etc. Though Gandhi lived there for only about 13 years – and during that period spent just 1528 days at the Ashram, since he was travelling all over – the Ashram has forever become a part of his identity.

The Years At Sabarmati

The years 1917 to 1930 that Gandhi spent at the Ashram were important ones in his life. “It was here that he acquired his first set of dedicated followers in India,” says Guha. Under Gandhi, the Ashram became the epicentre of Indian politics, he adds. “The birth of khadi as a national and Gandhian symbol was at this Ashram. He had started spinning before, but here he started a workshop to build spinning wheels. The Ahmedabad mill workers, went on a strike for higher wages in 1918. Gandhiji got involved in the protest and worked with the mill owners and workers to find a resolution to the situation,” says Suhrud. Many of the striking workers had been employed by Gandhi to build parts of the Ashram. The Kheda Satyagraha in support of peasants who couldn’t pay the high taxes levied by the British government, was launched in this period.

In tandem with his political work, he also started putting in action his plans for social reconstruction. Along with Harijan seva and reviving khadi, Gandhi started editing journals like Navajivan and Young India during his years at Sabarmati, and in 1920 founded the Gujarat Vidyapith university. It was while staying at the Ashram that Gandhi was arrested in 1922, and tried for sedition (for publishing certain revolutionary articles) in what has since come to be known as “The Great Ahmedabad Trial”. Gandhi pleaded guilty and was jailed for six years, but released after two years for medical reasons.

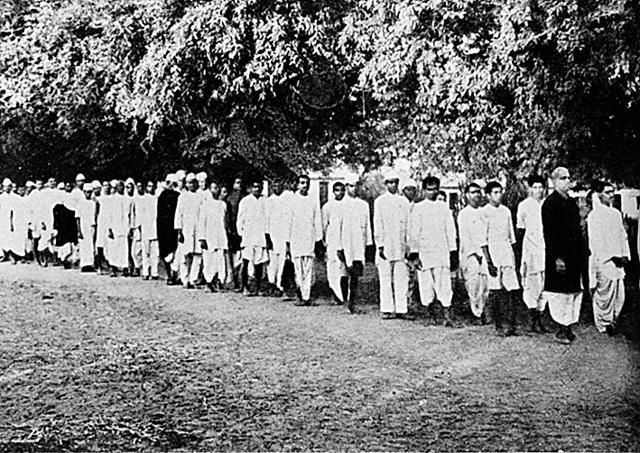

“Gandhiji also wrote his autobiography at the Sabarmati Ashram over a period of 658 days. When he wanted to be in touch with himself, this is where he would come,” points out Suhrud. His political movement against the British progressively intensified over the years and finally in 1930, along with 78 other volunteers from the Ashram, Gandhi set out for the historic salt march to Dandi, to break the British law that stopped Indians from producing or selling salt, vowing not to return to the Ashram till India had gained independence from the British. “He never lived at the Ashram after that though he visited a few times. His last visit to the Sabarmati Ashram was in 1936,” says an Ashram employee.

When Gandhi Left

“After Gandhiji left (in 1930), volunteers and other leaders who stayed back or visited the Ashram carried on the work of social reconstruction started by him,” says Guha, adding that the political nerve-centre of the movement shifted with the leader. Then, in 1933, three years after leaving the Ashram, to protest the torture of those connected with the freedom struggle and the forced taking away of their properties by the government, Gandhi decided to disband the Ashram and wrote to the secretary of the government of Bombay, suggesting that the government “take possession” of the land, buildings and crops of the Ashram. “I clearly see that the vast constructive programme of the Ashram cannot be carried on with safety unless the Ashram ceases entirely to have anything to do with the campaign. To accept such a position will be to deny the creed.”

When the government did not take possession of the Ashram, however, Gandhi decided to dedicate it to the service of Harijans. A new trust was formed for this.

“…The Ashram exists in our hearts as much as it does on the bank of the Sabarmati,” Gandhi had written in a letter in 1932. “When he thought that the institution established by him had served the purpose for which it was established, he was ready to disown it. Whether it was his Ashram or the Congress, he decided on merit and there was no personal attachment. This is the uniqueness of Gandhi,” says A Annamalai, director of the National Gandhi Museum in Delhi. Suhrud agrees: “His own ideas and philosophies were evolving. From having his base in the city, as in Ahmedabad, he had realised that change had to be brought in through the villages, and Sevagram, the institution in Wardha in Maharashtra, created after Sabarmati Ashram, was a reflection of this,” says Suhrud. The objectives of the two institutions were different, points out Annamalai. While Sabarmati Ashram was established to train volunteers for non-violent action, at Sevagram, Gandhi wanted Congress workers to settle in a village and engage in rural reconstruction through constructive programmes.

After His Death

In the years after Gandhi’s assassination in 1948, different trusts have taken up the work of conserving and protecting his legacy and carrying on the work started by him at Sabarmati. The Harijan Ashram Trust runs the Vinay Mandir school for higher education and the Mahila Adhyapan Mandir with hostel facilities for Harijan girls. The Gujarat Khadi Gramodyog Mandal produces and sells khadi and runs a unit for building charkhas and also a unit for handmade paper called Kalamkhush. The Khadi Gramodyog Prayog Samiti does research in spinning, weaving etc, while the Harijan Sevak Sangh works for the removal of untouchability and does research in modern, low-cost sanitation. It also runs the Safai School. The Ashram Gaushala engages in animal husbandry, cow breeding and milk production.

Then there is the Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust. “It was formed in 1951 with three major objectives – to preserve the physical buildings, his residence etc; to collect and preserve his writings; and a third, very critical part, was communication – how does the modern generation know about Gandhi,” explains Kartikeya Sarabhai, the longest-serving trustee. The Trust has taken up projects such as a non-violence programme in schools, to teach children the importance of finding solutions to problems by non-violent methods. “We don’t engage in politics,” he adds, “but we try to organise programmes to give answers to modern social issues through Gandhiji’s teachings,” he says.

One of the most important works of the Sabarmati Ashram Preservation and Memorial Trust has been to create the Gandhi Heritage Portal, which in the last six years, has digitised his writings, journals , photos etc, besides creating virtual tours of places associated with Gandhi. Three dimensional models of objects used by him are being added. “The portal not only has matter available here, but at other Gandhi institutes too. We have even sourced material from South Africa and put it on the portal,” says Sarabhai.

As far as the Ashram goes, Annamalai feels, a good idea would be to accommodate people at the Ashram at Sabarmati, to experience Ashram life and follow the Ashram rules and routine. “In that way it can become a living model of a Gandhian life style,” he says.

The years since Gandhi’s death have not been without discord. Last year, descendants of Harijan families living in the Ashram protested during the centenary celebrations because they felt they had not been made part of the event. There is also friction between individuals and groups on the use of the Ashram land. While Pandya agrees that there is at times disagreement between parties, he insists that even during Gandhi’s time, differences would crop up between various groups.

On a typical day at the Ashram, however, peace still prevails. The odd, shrill notes of a Bollywood song from a visitor’s mobile phone is all that disturbs the quiet. As the hot summer day gives way to a balmy evening and the Ashram prepares to wrap up for the day, a few stragglers sit on the stairs leading to the river bank, soaking in the breeze and the serenity.