The longest week in the life of a family in Srinagar

Ahmad, 40, and his family landed in Srinagar on July 12 with a vacation on their mind. They would stay in their ancestral home, drive up to Pahalgam and Gulmarg, a long-earned break from the oppressive heat of Dubai, where Ahmad works in a logistics firm, and celebrate Eid at home before returning to Dubai on August 28.

For someone unfamiliar with the bylanes of old Srinagar, Bilal Ahmad’s home in Nowpura is impossible to find. From the main crossing, one has to turn on to an old bridge, bursting with carts and shopkeepers, before leaving one’s vehicle and walking into a cramped lane, where buildings, cheek by jowl, share terraces and there is so little distance between the windows of two buildings that things are often passed by hand.

Ahmad, 40, and his family (wife and two children) landed in Srinagar on July 12 with a vacation on their mind. They would stay in their ancestral home, drive up to Pahalgam and Gulmarg, a long-earned break from the oppressive heat of Dubai, where Ahmad works in a logistics firm, and celebrate Eid at home before returning to Dubai on August 28.

Before long, rumours started swirling that a shutdown was coming. On August 4, he took the family out to see an aunt; on the way back around 6pm, they stopped at the local Sunday market to pick up some goodies for the children.

“It seemed like everything was on fire. People were shouting that a war might break out soon. We picked up some oats, potato, onions, dry vegetables, and milk and chocolates for the kids. From another shop, we got some chicken,” he said.

The family had already stored flour and rice for the month — a practice perfected during months-long shutdowns in the militancy-hit 1990s. Ahmad thought they’d need petrol and cash at well, but long queues at five pumps and ATMs dissuaded him. I’ll get it tomorrow, he thought.

The family returned home uneasy and Ahmad’s wife, who refused to be named, put their two children, Zainab and Mohammed, to bed early. Ahmad was on the phone talking to his mother in Dubai at around 11pm when the lines suddenly went dead.

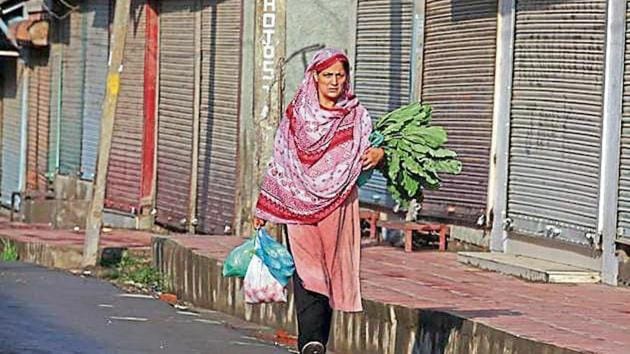

Around 5am on August 5, the sound of jackboots on the road outside, and announcements of restrictions — in preparation for India revoking Jammu & Kashmir’s special status later that day — woke him up. “I went to the washroom outside, and, from the window, I could see three military vehicles,” he said.

The first two days were tough. With phone lines and most cable television networks snapped, and curbs on movement, there was little news of what was going on. The only information trickled through the bylanes of the old city, where there were no security personnel. “But it fuelled a lot of rumours. Every day, we would hear about attacks, deaths and protests, and didn’t know what to believe,” Ahmad said, as he changes Mohammad’s diaper.

The blockade upended their everyday life.

Vacation plans shelved, the family spent most of their time in the carpeted and cushioned living room — with a fridge in one corner and a television in another. The parents kept the children distracted, teaching Mohammed how to fold his hands, say hello to people, or do the adaab, but worried every time Zainab had to go to the washroom; in 2016, during the protests that followed the killing of militant Burhan Wani, a pellet had ricocheted off a wall, and narrowly missed the five-year-old’s head when she was in the washroom.

A box of rasgullas that Ahmad had brought was used as treats for the children. “We would keep them locked up in a room, and panic if they demanded to go out even a little,” he said. Elaborate breakfasts were replaced with cookies and biscuits, and the family shed its aversion of chicken. “My favourite Korma was gone from the menu,” Ahmad said. For the children, there was mostly soup.

A big problem was milk. The family had bought three litres on August 4, but couldn’t procure any more because they had only one refrigerator. Neighbours chipped in with packets of powdered milk but it gave Mohammad indigestion. In the absence of medicines, yoghurt had to suffice.

The apprehension affected their mental state too, Ahmad said. “We were jumpy, anxious. If the children made a mistake, or asked for something, I would shout at them,” he said.

The house didn’t have air conditioning, and the possibility of tear and pepper gas shells forced the family to cover the windows with curtains and cloth, making the house unbearably stuffy.

Things started looking up on August 7. The cable network was restored — ensuring the cartoon channel, Pogo, would keep the children occupied — and Ahmad was able to buy a newspaper that confirmed that the situation was calm, if tense. That afternoon, he ventured out of his home for the first time in three days, going for a stroll in the local chowk, and noticed heaps of garbage piled up on street corners. “My in-laws came and gave us some more cash and a friend dropped off some milk,” he said.

The next day, Ahmad’s friend, Mushtaq Wani, came for a visit, and brought with him tales of a barricaded city. “I had to spend three hours trying to get there, because five different roads were blocked,” he added. For Friday prayers, they chose to go to the neighbourhood mosque instead of their usual one.

With Eid fast approaching and the authorities relaxing restrictions, Ahmad finally took out his Santro on August 10 to drive to the local market.

He got some cash and petrol, but could only lay his hands on one sheep, and said he would not be able to find a butcher for the traditional Eid morning Qurbani. Most traditional butchers, or Kasai, travel from neighbouring districts into Srinagar.

“I think we will have to celebrate Eid a day late because the butcher is only available then,” he said on Sunday. “Anyway, it matters little because I don’t even have enough money to give Eidi (traditional cash gifts) to my children,” he said.

The Ahmads are relieved that they are safe and plan to cut their trip short and return to Dubai next week because they don’t know how the situation will evolve after Eid. Their house is in the heart of the old city, the epicentre of protests. Ahmad says Kashmir holds little promise for the children. “It’s a battle of egos and a political game on all sides. The uncertainty is killing us.”