Slowing economies, divergent outlooks: BRICS needs mortar to be relevant

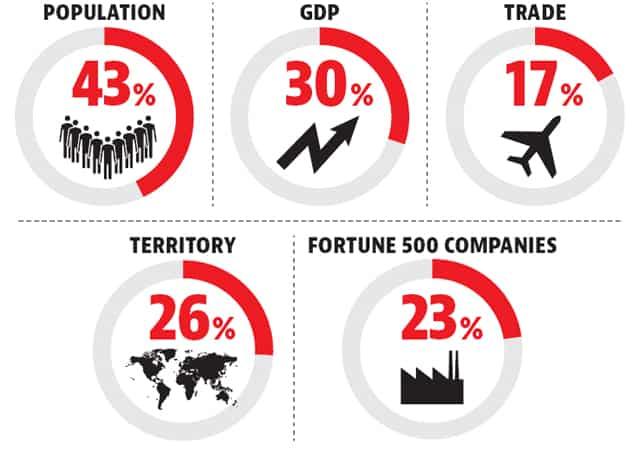

The hope from BRICS was that it would bring equity to global economic architecture and offer a political counterweight to model that would match the advanced West. A decade on, as leaders of the five member nation meet at the 8th annual summit, that ambition remains to be realised.

When Goldman Sachs economist Jim O’Neill coined the term BRIC in 2001, the world was a different place. Brazil, Russia, India and China – as the acronym goes – held out hope for a world that, at the time, was battling the decade’s worst economic slump, growing inequity among rich and poor countries and a new face of terrorism in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks.

China’s sustained double-digit economic growth, the steady emergence of India as a global hub for outsourced services and the prospects of Russia and Brazil riding on an oil and commodity boom made an economic and political alliance of these countries a proposition whose time had come.

So, BRIC was born in 2006, later expanded to include South Africa and become BRICS – stoking hopes of a new world order that would balance economic interests of the advanced West and the rest, ensure a fair deal at multilateral negotiations and help lift millions of the world’s population out of poverty.

A decade on, however, as the leaders of the five countries go into a huddle Sunday, for their 8th annual summit in Goa, they confront a different reality.

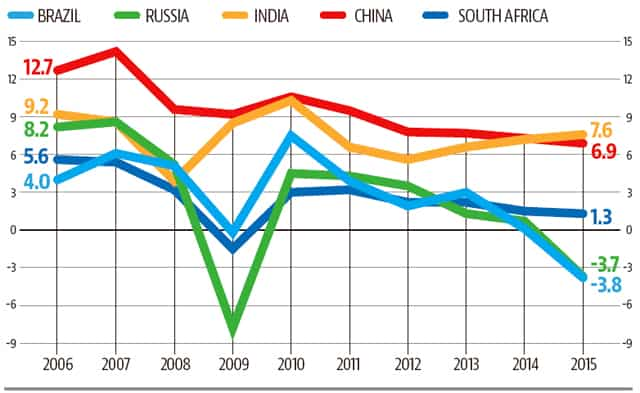

Their economies have significantly slowed down in recent years. Brazil and Russia, hit by falling oil and commodity prices and corruption-stoked political turmoil, saw their economies contract last year. South Africa is growing at a sluggish 1%-plus pace, while China’s double-digit growth has become a thing of the past. In 2015, it slipped to 6.9% -- the lowest in 25 years. India offers a silver lining, with a respectable 7%-plus growth, but is hemmed in by high inflation and rising unemployment.

The slide of the these economies prompted Goldman Sachs, where the idea of this grouping originated, to fold up its BRIC investment fund last November, after a sharp fall in the value of its assets.

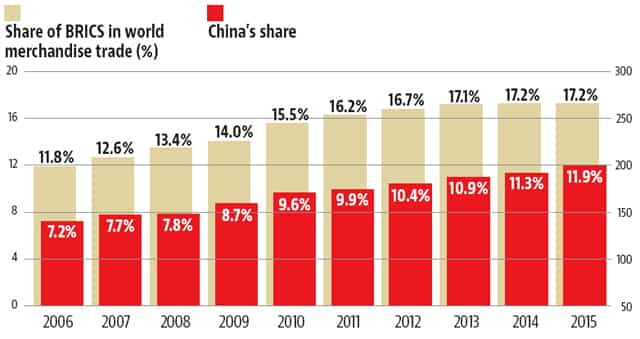

Over the past decade, the share of BRICS countries in world trade has increased from 11.8% to 17.2%, but most of it has been on account of China, whose share rose from 7.2% to 11.9%. South Africa’s has remained flat, while Russia’s share has fallen and Brazil’s is marginally up. India has done relatively better, going up from 1.2% to 2%.

But where the group gets a thumbs-down is in its failure to push trade within the member countries. Intra-BRICS trade totalled about $244 billion in 2015, less than 1% of world trade – underscoring structural weaknesses in the economic alliance. The imbalances are most pronounced in the case of India and China. While bilateral trade between the two countries has soared to $70 billion, it has left India with unmanageable hole of $50 billion in trade deficit with China, the largest with any country.

China’s economic dominance has also kept the group from exploring any free trade agreement among them, for the fear that their already-struggling economies would get flooded by low-cost Chinese goods.

“The trade and investment-motivation is no longer a sufficient driver for the BRICS”, said Hannes Ebert, research fellow at German Institute of Global and Area Studies in Hamburg.

Floundering BRICS?

Slowing economies and trade imbalances are only one part of the story. The divergence in the strategic outlook of Russia, China and India and their choice of global allies has made BRICS a less cohesive grouping than what it was when the first summit was held in 2009.

India and China have not found a way to address thorny bilateral issues. The longstanding border dispute remains unresolved and prone to generating tensions along the Line of Actual Control that inevitably galvanise nationalists on both sides. Beijing has yet to support India’s bid for a permanent UN Security Council seat or its entry into the Nuclear Suppliers Group. It is currently blocking India’s attempt to put Masood Azhar of the Jaish-e-Mohammed on a UN list of proscribed terrorists, a key objective for the Modi government. The Chinese government, on its part, is irked with India coming on board with the US for a joint strategic vision for the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean region that seeks to draw in Japan and Australia as a counter force to China.

During a bilateral meeting held ahead of the summit, Prime Minister Narendra Modi nudged Chinese President Xi to forge a common ground on cross-border terrorism – an euphemism for action against Pakistan that New Delhi accuses of shielding terrorists like Azhar. But the Chinese remained non-committal, even though Xi agreed with Modi that terrorism was a key issue and the two countries should be together in the fight against this ”scourge for the region.”

Read | Russia with India on terror but China still on the fence ahead of BRICS summit

India-Russia ties have weakened over time; India remains an important importer of Russians weapons and energy but Moscow is miffed about Delhi’s pronounced tilt towards Washington. The recent first ever Russia-Pakistan joint military exercise in Khyber-Pakhtunkhwa was Moscow’s way of signalling that it should not be taken for granted by Delhi. India conveyed its displeasure to Moscow and both sides have since moved to underplay the development and tried to shift the focus to more strategic issues by signing a clutch of big-ticket defence and energy deals on Saturday.

Read | ‘Old friend’ Russia’s stand on combating terrorism mirrors our own: Modi

At the other end of spectrum, Brazil and South Africa are distracted by internal political turmoil. Large-scale corruption scandals involving state-run firms and political parties have thrown Brazil, the world’s seventh biggest economy into political chaos, triggering a regime change earlier this year. Under its new president, Michel Temer who is seen as a close ally of the US, Brazil stares at a possible reversal of economic and foreign policies of the one and half decades, including its pivotal role in BRICS, that put the country on the global map.

South Africa is witnessing a constitutional battle over the millions of dollars spent on renovating President Jacob Zuma’s house and several other corruption scandals that is constantly undermining the legitimacy of the ruling African National Congress. Clearly, leaders preoccupied with domestic affairs can only have so much bandwidth for pursuing multilateral outcomes.

Yet, no one is giving up on BRICS. And there couldn’t be a more opportune time for India to host this summit that can turn the tide.

Hope floats

The view that BRICS may be floundering, some argue, is unjustifiably based on short-term economic trends and lacks a fuller appreciation of the rationale for such a grouping.

“The BRICS is still young,” wrote Song Guoyou, in an article published in Global Times, a Chinese state-run newspaper focused on international affairs. “It is no longer merely a passing economic phenomenon; it has played a vital role in the global economy, as well as in global politics and security.”

Song, who is the director of the Centre for Economic Diplomacy at China’s Fudan University, sees Russia and Brazil coming out of the slump sooner than expected. As long as China maintains its growth around 6.5% and India sustains its pace, the BRICS’s share of the global economic space will continue to increase, giving it a greater say in world affairs, he said.

“Economic growth may go up and down but what the five countries have in common is that they are all emerging economies seeking a new place at the global high-table,” said Shashi Tharoor, former minister of state for external affairs.

Nor would he see the political difference between India and China, two of the fastest growing economies in the bloc as a worrisome signal.

“The BRICS agenda is very wide and all-encompassing and deals with many other issues that are important to global governance and the individual BRICS nations,” said Samir Saran, vice president of Observer Reasearch Foundation, a New Delhi-based think tank.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi has already signalled that India would not allow the Summit’s focus go off the core agenda, even though it plans to raise its concerns about terrorism and seeks to resolve its differences with China in bilateral meetings.

“As BRICS chair this year, India embraces a stronger emphasis on enhancing economic and people-to-people ties,” Modi tweeted ahead of the Summit. “This will benefit us greatly.”

Modi has also invited leaders of the BIMSTEC group comprising Bangladesh, Bhutan, Nepal, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Thailand as part of a first-of-its-kind outreach at the BRICS summit. He will be holding bilateral meetings with each of them, on the sidelines of the summit.

The initiative serves a dual purpose. It allows BRICS members to explore collaboration and economic opportunities in the BIMSTEC countries, while allowing New Delhi to further its attempt to isolate Pakistan in the region.

India’s intent to make the Goa summit a defining moment in the BRICS journey has also played out in an expansive set of preparatory activities, including a trade fair, depicting famous monuments of BRICS countries through sand art on a picturesque beach of South Goa and hosting a U-17 football tournament that concluded Saturday at the Bambolim Stadium.

That said, the bonhomie in Goa could go either way. It may succeed in putting BRICS back on track, with new initiatives, renewed vigour and a bolder resolution on the part of its leaders to forge ahead; or it could get overshadowed by political bickering over bilateral issues. A lot rides on Prime Minister Narendra Modi who gets to steer Sunday’s summit.