Setting the nation to rights: From prison reforms to refugee rights, 25 years of the NHRC

The National Human Rights Commission completes 25 years this year. As an advisory body, the Commission has acted as a moral force on the State and seen some successes, even as it has faced failures. What needs to be done to make it a truly effective agency?

“When I started visiting prisons in the 1990s as the special rapporteur of the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC), the condition of jails was very poor. Overcrowding was one of the biggest issues and in one prison, I found inmates taking turns to sleep, because there wasn’t space for everyone to sleep at the same time,” says former director general of police Chaman Lal, who was associated with the NHRC between 1997 to 2006.

Constituted in October 1993, under the Protection of Human Rights (PHR) Act, the NHRC is currently in the 25th year of its formation. “We (India) have a Constitution, which fully imbibes the spirit of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, proclaimed by the general assembly of United Nations (UN) in Paris in 1948. But the real challenge lies in the lack of awareness about the law among, particularly, the lower level of officials, who mostly deal with and have a direct interface with the public,” says NHRC chairperson, Justice HL Dattu. He adds, “The Commission has a mandate to question only public authorities on their actions, omissions or inactions leading to human rights violations...”

Since its formation, the Commission has taken up some important projects and has, through its reviews, reports and recommendations, taken up the cause of prison inmates, patients at mental health asylums, bonded labourers, people with disabilities, women and children and the economically and socially marginalised sections of the country.

“It was widely felt at the time of creation of the NHRC that the body had been created under international pressure,” says Lal, though in an article he wrote five years ago on the Commission, he clarified that “there is no acknowledgement of the fact that the need for an external system of overseeing had arisen from the total failure of the in-house mechanisms (within each state department) to deal with complaints of violations of rights and abuse of power by the public functionaries.”

In an article in the Economic & Political Weekly (EPW) in February, Ujjwal Kumar Singh, teacher at Delhi University’s department of Political Science, points out that while the provisions of the PHR Act restrict the functioning of the Commission, making it at times a mere institution of the state, there “have been moments when the NHRC has opened the state to judicial and moral scrutiny”.

One example of this would be the consistent watch the Commission has kept on incidences of ‘encounter killings’ and deaths in custody. In 2012, replying to the observation made by UN special rapporteur Christof Henys on “fake encounters”, the NHRC observed that “since May 2010 the Commission has issued guidelines wherein every death in police action has to be reported to the NHRC within 48 hours of the incident. Prior to it, there were guidelines for submission of half-yearly reports by the State authorities in this regard”.

The NHRC has also been vocal in its opinion against laws such as the Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act (TADA) and Prevention of Terrorism Act, 2002 (POTA) – which had scope for misuse and possible human rights violations. In 1995, the then NHRC chairperson, Ranganath Misra, had written a letter to members of Parliament arguing that “The TADA legislation is, indeed, draconian in effect and character” and that “Provisions of the statute as such have yielded to abuse...”, and had appealed for its end. TADA was allowed to lapse in 1995. In 2000, when the POTA Bill was proposed, the Commission reiterated its stand against the need for any such law, citing “experience of the misuse in the recent past of TADA” and the adequacies of the existing laws as reasons. POTA was, however, passed in 2002, but was repealed in 2004.

Expanding Reach

Over the years, as awareness about the NHRC’s existence and work increased, so has its reach among the people. According to the Commission’s estimate, from 169 complaints received in 1993-94, the NHRC went on to receive 68,713 complaints in 2002-2003. The number crossed one lakh in 2007-2008 and was 1,17,808 in 2015-16.

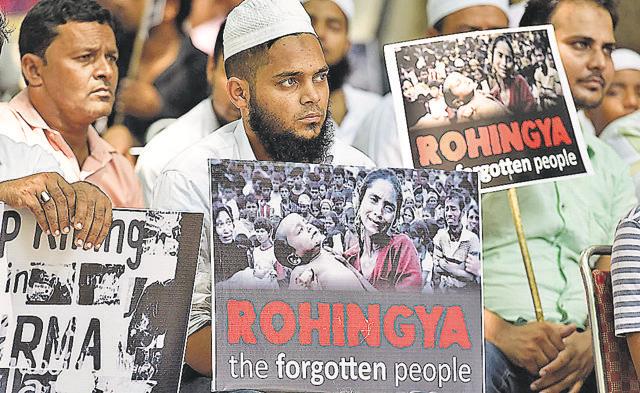

The Commission also takes suo motu cognisance of human rights violations, based on media reports or other sources of information and investigates them. In August last year, for example, based on media reports, the NHRC issued a notice to the Union Ministry of Home Affairs over the planned deportation of about 40,000 Rohingya immigrants, and asked the ministry to submit a detailed report within four weeks. Members of the Rohingya community, the NHRC had said in a statement, “have a fear of persecution once they are pushed back to their native country”.

This was not the first time that the NHRC has taken up the cause of any particular community or group of refugees. Soon after its creation, the NHRC in 1994 had taken up the issue of safety of the Chakma community in Arunchal Pradesh and in a letter to the state government had stated that it was “the obligation of that government to accord protection to the person and property of the members of the two communities (Chakma and Hajong refugees – Hindus and Buddhists of the erstwhile East Pakistan) and to ensure that their human rights were not violated”. In 1995 the NHRC also petitioned the Supreme Court (SC) for the protection of the rights of these communities, following which the apex Court in 1996 directed the Arunachal Pradesh government to ensure the same. The NHRC’s intervention had gone a long way in protecting the rights of the Chakmas in the north-east.

“The Commission also visits different states to organise open hearings to take cognisance of the problems of people there,” says former NHRC chairperson Justice KG Balakrishnan. While some of the open hearings are issue-based – the problem of bonded labour, for example – others address every kind of human rights violation. The Commission has also gone beyond the physical violation of human rights to protect the economic, social and cultural rights of people. Laxmidhar Mishra, another former NHRC special rapporteur, remembers being assigned to look into the extreme poverty, starvation and malnutrition in Kalahandi, Bolangir and Koraput regions of Odisha. Another of his assignments was to study the malnutrition-related deaths of children in 15 tribal districts of Maharashtra and submit recommendations for improvement in their living conditions. Mishra says that most of his recommendations in this case were accepted by the states. But that is not always the case.

On Slippery Ground

“The NHRC chairperson has himself admitted that the NHRC is a ‘toothless tiger’ with no authority to ensure that its recommendations were implemented,” says Shailesh Rai, director, law and policy, Amnesty International India.

The recommendations of the NHRC are not binding. Lal admits that while in over 90 per cent of cases financial compensation recommended by the NHRC is paid to the victims by the concerned authorities, the Commission has had very little success in getting the guilty punished. “The NHRC may, however, move the SC if its recommendations are not accepted,” says Lal.

One example of this is the Gujarat riots of 2002. “One of the important recommendations by the NHRC was that in five cases – including the Best Bakery case and the Bilkis Bano case – there must be a CBI investigation. But the state government did not accept this and said that the state and state-appointed panels will carry out the investigation. NHRC, along with some civil society groups, took the matter to the SC and later a Special Investigation Team (SIT) was constituted to investigate some of the serious cases,” recalls Lal.

The Commission also has limited powers over the defence forces. “Unlike in most other countries, the NHRC has the power of a civil court. It can conduct investigations into any allegation of human rights violation, summon any person during the course of the investigation and reach conclusions based on it,” says Justice Balakrishnan. But this is not so in the case of the armed forces, where on receiving a complaint or while taking suo motu cognisance of a violation, the Commission can only ask for a report from the concerned department and make recommendations based on it.

This becomes a major handicap for the Commission in states under AFSPA or the Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act – such as Jammu and Kashmir and Manipur – where allegations of violations are common. “In the Manipur fake encounter case, where 1528 people were extra judicially killed, the NHRC did not say a word for years,” says senior advocate Colin Gonsalves. However, the NHRC may not be in a position to intervene in such cases. In September 2016, Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi, on behalf of the Centre, opposed the NHRC’s offer to probe over 1500 cases of alleged extra-judicial killings in Manipur and said even the top court cannot “transplant” any powers on the panel. In July, the court had said that the alleged extra-judicial killings by the Army and Manipur police, over a period of 12 years between 2000 and 2012, required a thorough probe. But in February this year, the SC, dissatisfied with the investigations of a SIT formed by the CBI to look into some of the cases, directed the NHRC to depute three people to associate with the SIT to carry out investigation in 17 of 42 incidents in which cases have been registered.

“The NHRC has been of the view that the AFSPA should be repealed,” the Commission had said in response to Henys comments in 2012. “However, the SC has held that the Act is constitutional.” Now, the NHRC feels it is for the Centre to decide whether AFSPA should be continued.

A bigger issue is the very nature of formation of the NHRC – by an Act of Parliament and where the chairperson and the members of the Commission are appointed by the President, on the recommendations of a committee that includes the Prime Minister – which has raised doubts in the minds of many about its ability to function independently. “The NHRC is not a government body. It is an autonomous body, set up by the government in tune with its obligations under the Protection of Human Rights Act, 1993,” says Justice Dattu.

The Road Ahead

But as he himself points out “The SC has dwelt at length upon the constraints of the NHRC...” The SC has also said that the provisions of the PHR Act make it an obligation on part of the Centre to “provide adequate officers and staff so that the NHRC can perform its functions efficiently.”

One of the biggest successes for the NHRC in the last 25 years has perhaps been its ability to raise awareness about the need for human rights protection in the country and to initiate a dialogue on the same. “In future, the NHRC’s attention is also going to be towards new emerging concerns like business and human rights, environmental impact on human rights and LGBT rights,” says Justice Dattu. The journey won’t be easy, as it will doubtless involve pushing the government and the legislation in a direction it may shy away from. The Commission, if it wants to dispense its duty sincerely, may have to first fight for its own rights to protect those of others.