RBI survey shows a tight monetary-fiscal policy might boost anti-incumbency

In a highly unequal and largely informal economy such as India’s, economic policy-making is mostly about balancing voter and market sentiment.

Narendra Modi’s government will face elections in less than a year from now. The forthcoming assembly elections in the five states of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Telangana and Mizoram have kickstarted the election season. The state of the economy plays an important role in influencing voter behaviour.

In a highly unequal and largely informal economy such as India’s, economic policy-making is mostly about balancing voter and market sentiment. Some examples can make this clear. Cutting tax rates to bring down the prices of petrol and diesel, has a lot of populist currency. Such a move, however, will unnerve markets and international economic institutions. This is because they will be fearful of a fiscal slippage due to loss in revenue. Similarly, a rise in interest rates will probably cushion the rupee’s value vis-à-vis the dollar. Higher interests rates mean greater returns for foreign funds parked in India. But rising rates will generate headwinds for domestic business activity.

A tight monetary (higher interest rates) and fiscal (not cutting petroleum taxes) policy will probably help the rupee and keep the fiscal deficit under control. But it will also have a deflationary impact on the economy. The latter can have adverse consequences for a government seeking re-election. In today’s globalised world, ignoring mainstream market sentiment can also lead to adverse implications. For example, a recent Bloomberg report has held the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) responsible for the depreciating rupee. Such commentary can further accentuate the rupee’s fall.

It is relatively easier to find out the perception in markets. International institutions and rating agencies issue periodic bulletins on present and future health of economies. But no such measures exist for reading voter sentiment.

RBI’s consumer confidence surveys (henceforth survey), can give us some idea of the situation on this front. To be sure, the survey is conducted in 13 major cities and therefore does not capture the mood in rural India.

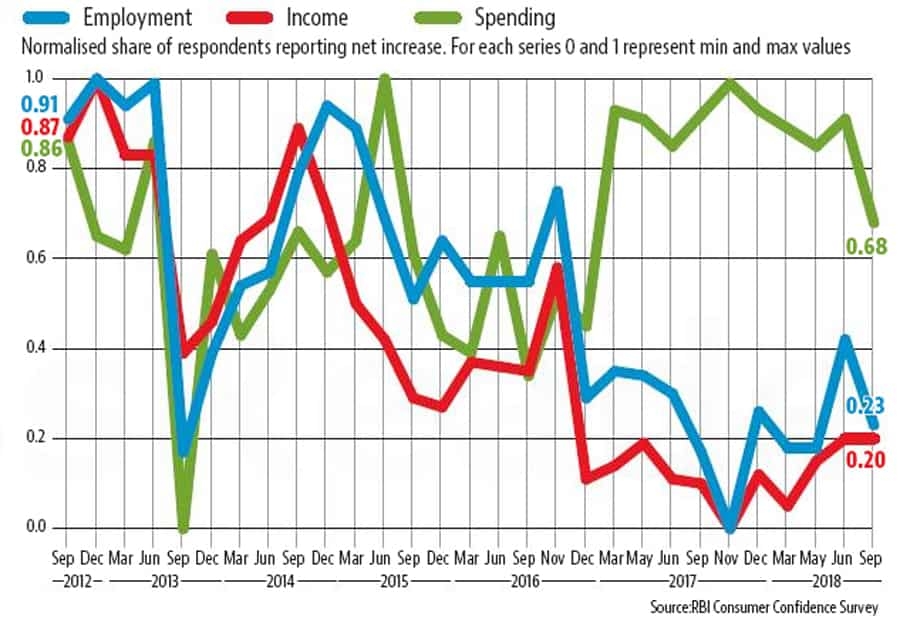

We look at the trend in three important variables from the survey: income, employment and spending. Looking at the three indicators together is important because it gives a holistic picture. If income and employment have been rising, then even an increase in spending might not be a bad thing for a respondent. Similarly, a fall in spending along with falling incomes and employment might signify an economy in deflation.

The chart given below shows normalised values – signifying the lowest and 1 signifying the highest – of net responses on current perceptions about income, employment and spending from the survey. (See chart)

All these values fell sharply between September 2012 and September 2013, which was just before the last major cycle of assembly elections before the 2014 polls. The Congress suffered major losses in these elections. There was a subsequent recovery followed by a short cycle of decline and increase until November 2016; the month in which demonetisation was announced. The three indicators were moving almost in tandem until this period. The post-demonetisation period has seen a break between movement in perceptions on spending and income/employment with the former rising at a much faster pace than the other two.

This trend has an important policy takeaway. A policy which tilts towards deflationary measures to control prices might actually put greater squeeze on incomes and employment. On the other hand, an improvement in income/employment sentiment, even if it comes at the cost of rise in prices, might not be a bad thing for the government. That’s a clear signal for the government on what it needs to focus on.