Number Theory: Women in the workforce and the underlying stress

A big gender gap in labour force participation rates (LFPR) – the share of population working or looking for a job – has been the cause of major concern in India.

A big gender gap in labour force participation rates (LFPR) – the share of population working or looking for a job – has been the cause of major concern in India. However, the recently released Periodic Labour Force Survey (PLFS) for 2021-22 shows that LFPR for women has been consistently increasing since 2017-18.

While rising LFPR for women is indeed a welcome trend, a careful analysis of PLFS unit-level data shows that this could be the result of some sort of underlying distress in India’s labour markets, especially in urban areas. Here are five charts which explain this argument in detail.

The trend in LFPR for women

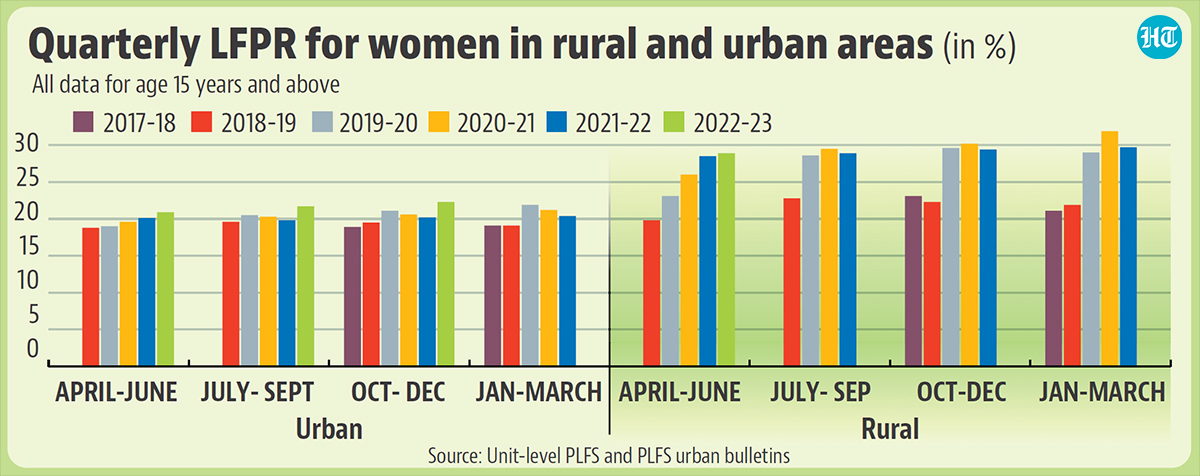

On an annual basis – PLFS reports cover the period from July to June – LFPR for women has increased from 23.3% in 2017-18 to 32.8% in 2021-22. While the biggest rise is seen for rural women, urban women’s LFPRs have also risen from 20.4% to 23.8%. A quarterly analysis of PLFS data shows a consistently rising trend in LFPR in both urban and rural areas after the second wave of the Covid-19 pandemic.

What is leading to the rise in LFPR for women?

LFPRs increase either because more women enter the labour force (rising entries) or fewer women leave (falling exits). Fortunately, PLFS allows us to give an informed answer to this question for urban areas at least. In the current PLFS, urban individuals are interviewed once every quarter for four quarters, which makes it possible to track aggregate labour market flows over time. This can be used to estimate the role of entry and exit from the labour force on the overall LFPR.

Exits from labour force have fallen after the pandemic

Using data from the quarterly bulletins of PLFS, we construct two measures quantifying exit from the labour force. E-OLF shows the share of employed women who leave the labour force in the next quarter and U-OLF the share of unemployed women who leave the labour force.

Before the pandemic, about 25% of all unemployed women in any quarter left (U-OLF) the labour force in the subsequent quarter. Exits from employment (E-OLF) were relatively lower but still significant. During the lockdown (Jan-March 2020 to April-May 2020), while the U-OLF flow fell, the E-OLF flow rose. The fall in the labour force was driven by employed women who, having lost their jobs, left the labour force entirely. Both U-OLF and E-OLF have fallen post-pandemic. In April-June 2022, only 10.5% of unemployed women and 6.4% of employed women left the labour force, a significant reduction from earlier values. Simply speaking, this means that women are now staying for longer in the labour force, holding on to previous employment or spending longer time searching for jobs.

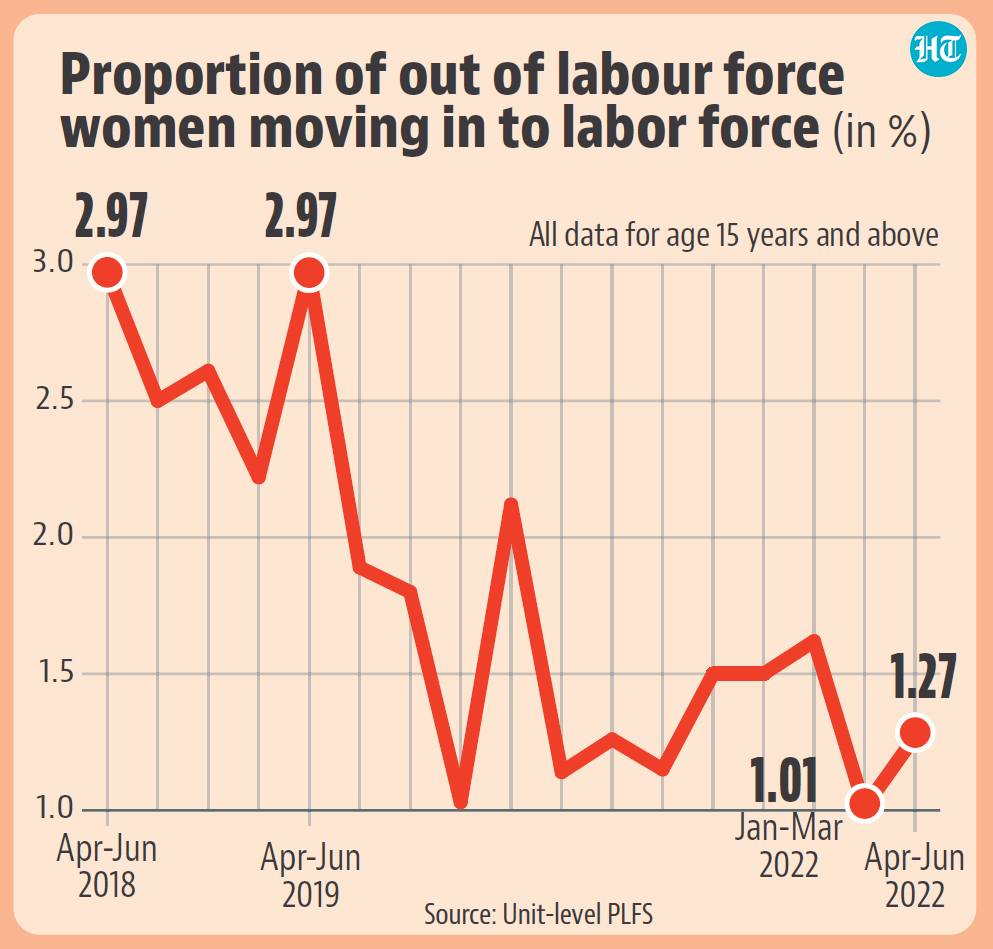

Entry into labour force has also come down for women

We estimate entry rates by calculating the proportion of women out of the labour force in any quarter who enter the labour force in the next quarter. We do not calculate entry into employment or unemployment separately, since the magnitude of these rates are low.

We find that the rate of labour force entry has fallen almost consistently in the period for which we have PLFS data. Reading the entry and exit numbers together, one can say that rising LFPRs are not due to more women entering the labour force, but a result of reduced exit rates.

Can we use these numbers to argue that there is rising distress in the labour markets for women? Two additional variables strengthen such an argument.

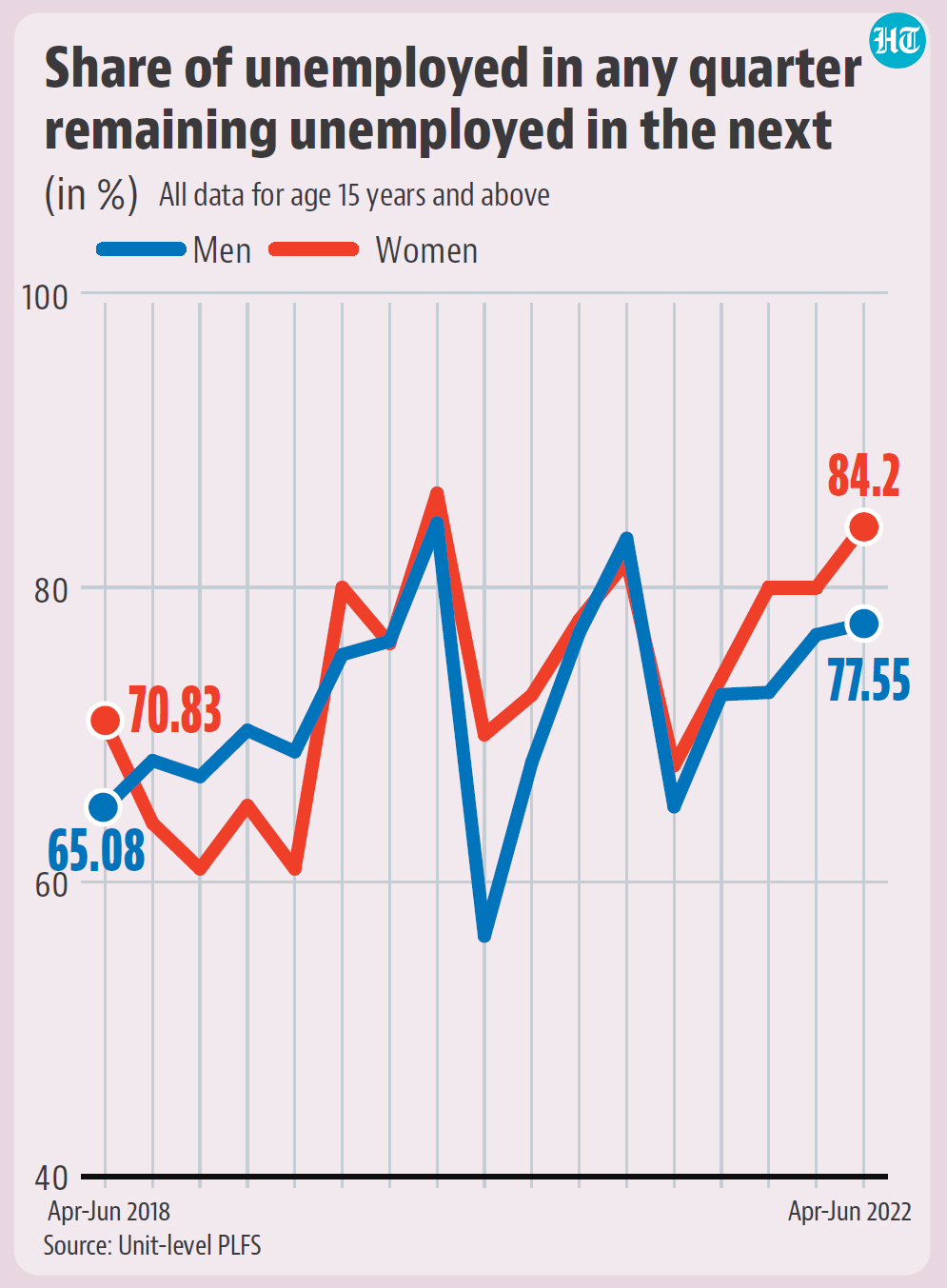

Persistence of unemployment is rising

The quarterly PLFS rounds also allow us to track unemployed individuals in any quarter remaining unemployed in the next. For both men and women, this has been rising since 2021, with the share for women rising higher than men since the pandemic.

And there has also been a rise in share of unpaid women workers

The composition of women’s work between January-March 2020 and July-September 2022 -- so as to compare periods before and after the two waves of the pandemic -- shows that wage employment, both regular and casual, has reduced and self-employment has increased, particularly the share of unpaid family work. Primary sector activities have risen at the cost of tertiary, indicating a reversal of structural transformation. In other words, LFPRs are increasing not because more women are finding better jobs, but on account of women staying in the labour force in hope of finding a job or staying in various forms of precarious employment.

(Rahul Menon and Paaritosh Nath teach economics at OP Jindal and Azim Premji University)

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website