Majority of bird species in India face decline: Report

There are now 178 bird species in India classified as “high conservation priority”

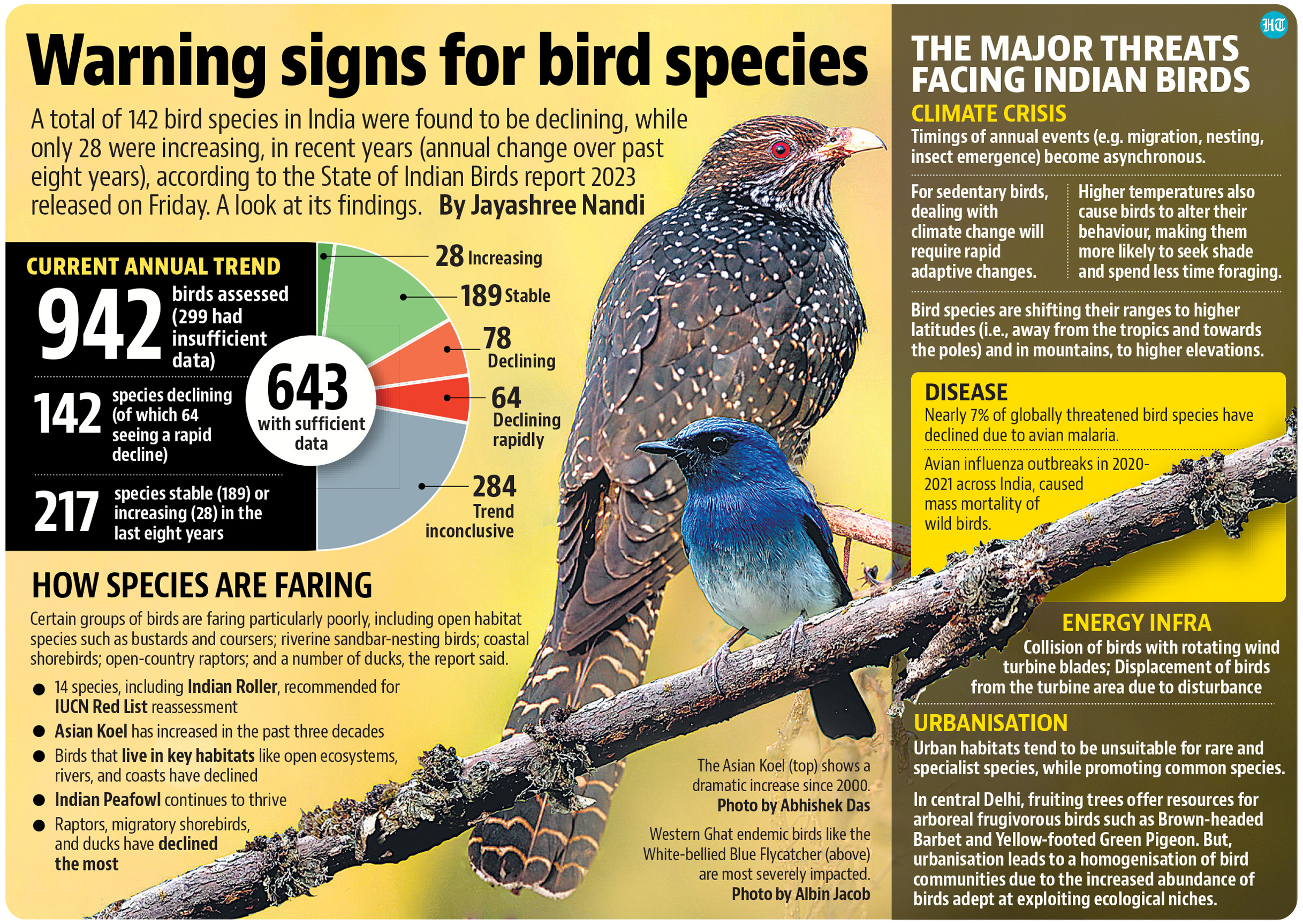

There are now 178 bird species in India classified as “high conservation priority” meaning that their abundance continues to decline after a considerable drop in the number over the years, and the sharpest decline in numbers is among species found in so-called open ecosystems or habitats, which typically have no protection. That number is up from 101 in the last report, released in 2020. Worryingly, the number of long-distance migrants has declined by 50%, with those that breed in the Arctic but winter in India seeing a decline of 80%.

These are among the key findings of the State of Indian Birds report 2023, released in Delhi on Friday. India’s birds are facing a significant decline in numbers revealing a silent, gradual change in population dynamics with around 60% of bird species recording long term decline in numbers and 40% showing an annual decline, according to the report.

The report, put together by around 50 experts from 13 premier institutions such as Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment (ATREE), Centre for Ecological Sciences, Indian Institute of Science (CES, IISc), Bombay Natural History Society (BNHS), Foundation for Ecological Security (FES), and Nature Conservation Foundation (NCF), revealed that grassland, wetland, woodland and other birds of open habitat are declining very rapidly. Species endemic to Western Ghats and Sri Lanka are particularly threatened. But, common species such as the feral Rock Pigeon, Ashy Prinia, Asian Koel and Indian Peafowl are thriving. The numbers of other familiar species such as the Baya Weaver and Pied Bushchat are also stable.

Certain groups of birds are faring particularly poorly, including open habitat species such as bustards and coursers; riverine sandbar-nesting birds such as skimmers and some terns; coastal shorebirds; open-country raptors; and a number of ducks, the report has found.

“The finding that a large number of common species are in trouble is cause for concern. Equally worrying is that a considerable number of species lack the data to be assessed. Insufficiency of data meant that of the 942 species covered in this report, long-term trend could not be calculated for 44% and current annual trend could not be estimated for 31% of the species,” the authors said in a statement.

The report is an upgrade to the first SoIB report released in 2020 at the Conference of Parties to the Convention on Migratory Species in Gandhinagar. SoIB 2020 and assessed 867 species out of the roughly 1,200 species that regularly occur in India. The report classified 101 species as being of high conservation concern in India.

The current report updates and expands the assessments from 2020 by adding observations during the past four years for 942 species. The assessments in this report are built on 30 million records from 30,000 birdwatchers across the country.

Specialist birds at highest risk

Birds with special habitats, as opposed to generalists that can live in multiple habitat types are far more threatened, the report has flagged. Grassland specialists have declined by more than 50%; woodland specialists (those found in forests or plantations) also declined rapidly indicating a need to conserve natural forest habitats. Migratory birds are facing decline due to several reasons including the dangers faced during migration, extreme weather events, starvation, and hunting/illegal killing. Migratory birds that breed in the Arctic are facing the most serious impacts of climate change, for example. Abundance trends of migratory species show long-distance migrants have declined the most, by over 50%.

Birds that feed on vertebrates and carrion have also declined suggesting that their food either contains harmful pollutants or they are largely unavailable. Evidence from other countries shows that agrochemicals lower survival rates in some raptors, the report states.

Birds that live in open habitats such as bustards have declined tremendously, the report underlines. Adaptable birds such as Yellowbilled Babbler and Jerdon’s Bushlark are doing well but more specialised open habitat birds such as Rufous-tailed Lark, Common Kestrel, and Isabelline Wheatear have declined more sharply. Great Grey Shrike, for example, has recorded long-term decline of more than 80%.

Riverine species that use open sandbars, rocks, and islets on rivers for their breeding are at significant risk. These include terns, pratincoles, Indian Skimmer, Little Ringed Plover among others.

Ducks also occupy a range of habitats, including inland lakes and tanks, submerged paddy fields, rivers, forest pools, and coastal lagoons. Large congregations of ducks occur in Chilika, Pulicat, Rann of Kachchh, Maguri, Loktak, Sambhar, and Keoladeo. But their flocking nature makes ducks susceptible to disturbances, habitat loss, and illegal killing and hence they too are facing rapid decline in India.

Birds outside protected areas

This report shows that many species that are rapidly declining are those with a large range and occupy habitats largely outside the formal Protected Area network. This means that effective conservation requires policies that extend beyond territory under the jurisdiction of forest departments. The authors have recommended effective conservation planning will require both interdepartmental communication and coordination, as well as close involvement of local communities and panchayats.

Birds that are thriving

Common birds including Ashy Prinia; Asian Koel; Indian Peafowl and the Rock Pigeon are recording an increase in numbers. Compared with the pre-2000 baseline, Asian Koel for example has shown a rapid increase in abundance of 75%, with an annual increase of 2.7% per year. In the past 20 years, Indian Peafowl has expanded into the high Himalaya and the rainforests of the Western Ghats. It now occurs in every district in Kerala, where it was once extremely rare. Its population density is also increasing.

The core team of researchers, during a press conference, said the compilation of data threw up a number of surprises. For example, Ashwin Viswanathan from NCF, said: “We found that the numbers of almost all duck species are reducing. The numbers of open habitat species are also declining. Spoonbills are rapidly declining too.”

Neha Sinha, head of policy and communications at WWF India, said: “Some common species have become less common because their numbers are falling, including the Indian Roller and Sirkeer Malkoha.”

All Access.

One Subscription.

Get 360° coverage—from daily headlines

to 100 year archives.

HT App & Website