Mahatma in a single frame

Gandhi realised the power of photography early on, for he used it strategically during India’s freedom movement later.

Being one of the world’s most revered photographers did not earn Margaret Bourke-White the right to photograph Mahatma Gandhi. In 1946, she had to also learn how to work the charkha before being allowed to photograph Gandhi doing the same. In notes that accompanied the film rolls sent to LIFE magazine’s New York offices, she wrote about how she thought of both the spinning wheel and photography as handicrafts, but Gandhi’s aides told her that spinning was the greater of the two. Gandhi, though, seems to have engaged with photography rather seriously from his early days in South Africa. There are several posed portraits of him as a young lawyer, with Kasturba Gandhi, as well as with members of the Natal Indian Congress in 1895.

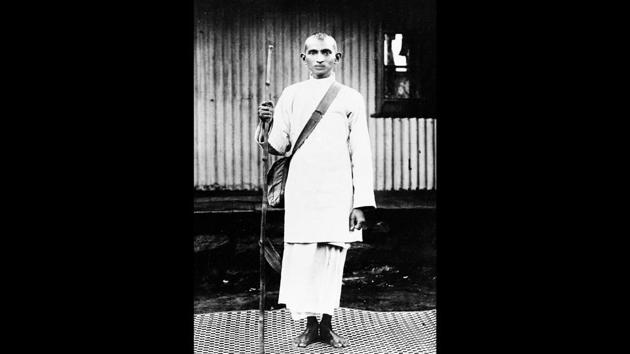

In January 1908, Gandhi was imprisoned for two months in South Africa for passively resisting the law that discriminated against Indians. There is a photograph from 1914, of a young Gandhi standing barefoot, wearing a sling bag, holding a stick and staring into the camera, with both fists tightly clenched. Similar in resolve is a portrait of women resisters who spent three months in prison, all looking solemnly into the camera, one even carrying a child in her arms. This kind of powerful imagery subverted the conventional use of posed photographs of that time, which were commissioned largely for posterity. Gandhi probably realised the power of photography then, for he used it strategically during India’s freedom movement later.

Not averse to posing for the camera in his early years, as is obvious from a series of studio portraits of him in 1915 in Mumbai, Gandhi can be seen posing against a backdrop wearing his turban, dhoti-kurta and a pair of sandals. Some months later, a similar photograph was recreated, with Kasturba next to him. The only difference being that Gandhi wore no footwear this time. “After Gopal Krishna Gokhale’s death, as a mark of respect, Gandhi didn’t wear sandals for a year. That explains the difference, but his desire to be photographed in the same manner remained,” said A Annamalai, director of the National Gandhi Museum, which has, in its collection, over 7000 photographs of Gandhi.

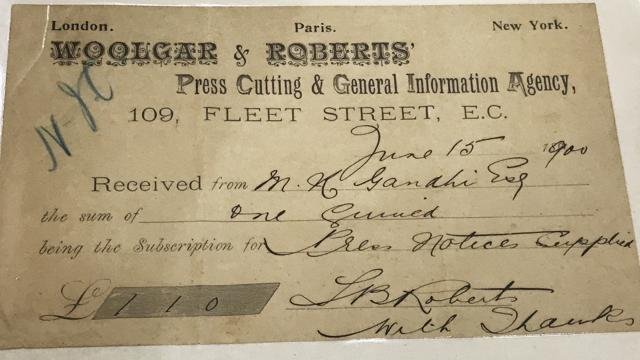

Gandhi was also keeping track of his published photographs and news mentions across the world. A payment receipt of a hefty £1.10 dated June 15, 1900, from Woolgar & Roberts’ Press Cutting and General Information Agency in London in Gandhi’s name, confirms his subscription to press notice clippings for a year. In the 1920s, during the Rowlatt Act satyagraha, Non Cooperation movement and the Bardoli satyagraha, local photographers were making hundreds of photos of non violent protests, marches and public meetings. What the international press wanted to see was Gandhi in private.

Swiss photojournalist, Walter Bosshard, was commissioned to travel across India by the German magazine, Münchner Illustrierte Presse, in 1930 to cover the social unrest and photograph Gandhi. “I have sworn to never pose for a photographer! Try your luck, perhaps it might even turn out well,” Gandhi told Bosshard when he met him. In Bosshard’s book, Indien kämpft!, published in 1931, there is mention of this conversation — possibly the first written record of Gandhi’s now changed relationship with the camera. The posed, studio portrait was now a thing of the past. A day after Gandhi broke the Salt law in Dandi on April 6, 1930, Bosshard made some endearing photographs of him.

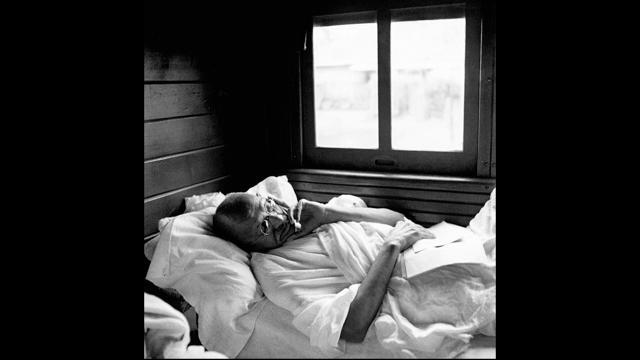

“In this relaxed atmosphere of Gandhi with his followers, Bosshard recorded Gandhi drinking soup, shaving, laughing at a satirical report in The Times of India, and speaking on the act of spinning with his closest confidantes,” said Gayatri Sinha, who co-curated an exhibition of Bosshard’s photographs of Gandhi and Mao Zedong last year at the Kiran Nadar Museum of Art in Delhi.

In the late 1930s, Gandhi’s grandnephew Kanu Gandhi began photographing the Mahatma extensively. He was given access, but on the condition of not using a flash, or having Gandhi pose. By this time, Gandhi was also signing his photographs for auctioning, so that money raised could be used for the Harijan movement. “Do rupiya ek bar”, he [Gandhi] would say, the floor price is two rupees,” writes Ramachandra Guha in Gandhi: The Years That Changed The World. Gandhi used the medium strategically to benefit India’s freedom struggle such that all non violent movements, marches, political and public meetings were constantly in public memory via the publication and personal circulation of his images. While still being rigorously photographed like perhaps no other figure of that time, Gandhi had consciously stepped out of the photo studio and into the public imagination.

When the celebrated French photographer Henri Cartier-Bresson met Gandhi barely half an hour before Gandhi’s assassination, they spoke about photography. “Death, death, death” is what Gandhi last said to Cartier-Bresson upon seeing his image of the poet Paul Claudel walking past a hearse. In his book Temperaments: Memoirs of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Other Artists, Dan Hofstadter recalls Cartier-Bresson speaking about the encounter.

Ironically, the most reminisced image of Gandhi by Cartier-Bresson was one without the leader in it. It was of Nehru’s address to the nation mourning Gandhi’s death as he spoke, “The light has gone out of our lives and there is darkness everywhere.” Just like a photograph before it is made.